The Book of Why

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author's intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author's rights.

For Nicole Michels

T

his

is

a self-help book.

Didn't think it was, but it is.

It's also a revision, a question, a confession, an apology, a love letter.

This book is for you, of course, and now for Gloria Foster, who might read this when she's older, might chance upon this book online or in a used book store in Philadelphia or New York or San Francisco, open to a random page, and see her own name. She might be struck by that and sit where she had been standing in an aisle and begin reading. She might put the book back on the shelf, though I doubt itâhuman curiosity is much too strong. The desire to know. The sense that there's too much we don't know. She might tell her parents, if her parents are still alive; her boyfriend, if she has a boyfriend; her husband, if she's married.

She might tell no one. She might be frightened, and for that, in case it happens, I apologize. Add it to my list of apologies. She might think, But I don't remember the man and woman who stayed with us. The man's dog. The big storm. Maybe, after she reads what I've written, it might begin to return to her. She could let it go, put it out of her mind: what happened when she was five no longer matters, what happened before she was bornâif the book is trueâmatters even less. But, the desire to know. She might try to find me, search my name on the Internetâby then, twenty years from the time of this writing, you'll probably be able to find someone just by thinking his name. Maybe that's just science fiction. But she'll find me, if she wants. I'll still live, if I'm still alive, on Martha's Vineyard, at the end of a dirt road that turns to bog in rain or snow. She'll find me if she's supposed to.

And what happens then? Does she believe me? Does she ask why I didn't tell her soonerâwhy

this

way, in a book? Does she ask for more details about youâyour likes and dislikes, your joys and struggles? Does she need to? Does she ask for a cup of tea? Does she sit on the couch and stare at me as if she's sorting through memories she's not even sure are her own? Does she become an intimate, a daughter figure, or perhaps evenâ

No. She'll be twenty-seven by then, a woman. But now she's a girl, and so I'll close that path in my mind.

HELLO AND WELCOME.

Thank you all for coming.

You are here for a reason.

Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and ask yourself why.

What would you like to accomplish today? What would you like to change about your life?

Maybe you're drowning in debt. Maybe you're stuck in a stressful, unrewarding job. Maybe you've chosen a career you know isn't your true calling. Maybe your marriage is falling apart. Maybe you're estranged from your children or your parents. Maybe you're battling an addiction or a serious illness. Maybe you're happy but want to be happier.

If any of these are true, you've come to the right place. No need to move for the next two hours; the only shift will take place inside you.

You have creative control over your own experience. You have the power to change your life, to revise the story you've been telling yourselfâconsciously or subconsciouslyâfor years, or to write a new story entirely. This transformation begins now with your next thought. In this room today there's no such thing as the past. By focusing on the present, by recognizing your conditioned way of thinking and reprogramming your default settings, you will create a future without limits.

Write this down and underline it: Happiness is an inside job.

Let me say that again: Happiness is an inside job. Happiness doesn't depend on what anyone else is doing. It doesn't depend on circumstances. If only this would happen, I'd be happy. If only that would happen, I'd be happy.

No more excuses. Happiness is an inside job. Your mind is the ultimate gift-giver. You need to understand: we live in an abundant universe. The universe is listening to your every thought. You are always broadcasting a signal to the universe, and this signalâthis wave of energyâwill always return to you. Every request is granted.

There are no accidents in this universe, only laws, and ignorance of the law is no excuse.

A current of energy runs through all things, including you and me; it doesn't know the word

no

. The law of attraction is no less absolute than the laws of physics and mathematics. Two plus two always equals four; this is true everywhere in the universe. It's something you can be certain about, a fact you can count on. No different with the law of attraction: you'll be able to create your future. No need to worry anymoreâyou are in charge, you are the scriptwriter, the director, the editor; you have final say. There's no need ever to feel like a victim; there are no circumstances beyond your control. It's as simple as simple math: if you focus your attention on something you desire, then by law it must come to you.

Ask, believe, receiveâthese are the three steps we'll be practicing today. Three steps to changing your life.

Number one: ask. Changing your mind's default settings. Redirecting your thoughts. Focusing on what you desire.

Number two: believe. Living as if you already have what you want. Keeping faith no matter what. Expecting miracles.

Number three: receive. Allowing abundance into your life. Getting out of your own way. Removing obstacles in your path, especially negative thoughts.

Because, believe me, negative thoughts can hurt you. Doesn't matter if they're conscious or subconscious. Our brains are computers; we're programming them all the time whether we're aware of it or not. You must be careful. Thoughts repeated become dominant thoughts. Dominant thoughts become default settings. Default settings become beliefs. Beliefs sustained manifest. Dangerous enough when thoughts and beliefs are conscious; much more dangerous when they're subconscious. Sometimes we become aware of subconscious beliefs only when they manifest in our lives. You can say you deserve a better job, you can say you deserve the break you've been waiting for, you can say you deserve health and peace and happiness, you can believe that you believe, but watch out for the subconscious. The conscious mind may say yes while the subconscious mind says no. So if you don't get that job, if you don't get that break

, if you do receive a serious medical diagnosis, then in the deepest, darkest parts of the computer inside your skull, you must not have believed that you deserved that job or that big break or that clean bill of health.

Let me be clear: the mind is always creating whether we want it to or not. We really do get what we're thinking about. When we desire, we create; when we worry, we create. Nothing can enter our lives without our invitation. Some people are uncomfortable with such responsibility, but we couldn't forfeit it even if we wanted to. No more cruel twists of fate to blame, no more acts of God, it's all up to us now. Which is why we need to reprogram our brains with positive thoughts; we need to clean out our files, scan our hard drives for viruses.

Ask, believe, receive.

If you spend a lot of time thinking about how terrible life is, then the universe says, “Your wish is my command,” and sends back to you people and events and circumstances that reflect your thinking. If you focus your thoughts on the joy and abundance in life, then the universe will say, “Here you go, more joy and abundance.” I assure you, I didn't make this stuff up. I'm just the messenger. I believe it, I try to live it, and I want everyone to know about it. I want you to have everything you want.

This isn't about greed. This isn't about being selfish. This isn't about people thinking about wealth and receiving a check for a million dollars in the mail. If you want more money, fine. Money's not a bad thing. Your poverty won't make a single poor person rich. Your sickness won't make a single sick person healthy. Imagine that line of thinking: Well, there are so many poor people in the world, I'm going to be poor, too. There are so many sick people, I should be sick, too. There's so much suffering, I'd like to help by suffering, too. Listen, the more you have, the more you can give. The universe has deep pockets. Abundance is meant to be recycled. There is always enough. You are a reflection of the universe, and the universe is generous; the universe never says no.

W

inter on Martha's Vineyard, five years after.

The tree in the yard, its limbs heavy with ice, leans toward the house. Branches crack under their own weight, shatter on the walkway. Wind swings the ice-coated hammock low to the ground. The front door is frozen shut.

It's been a few months since I've heard her sing, so I put on my favorite song. Her voice will never grow old, but this is the smallest consolation.

What changes is the listener, forty-two now, long-bearded, going gray, heavier than he used to be but still what most would describe as thin.

Her music isn't all that I have. I have photographs and a box of keepsakesâletters and doodles, a few sweaters, a pair of socks, her favorite books, notes in the margins, ditties that ended up in her songs.

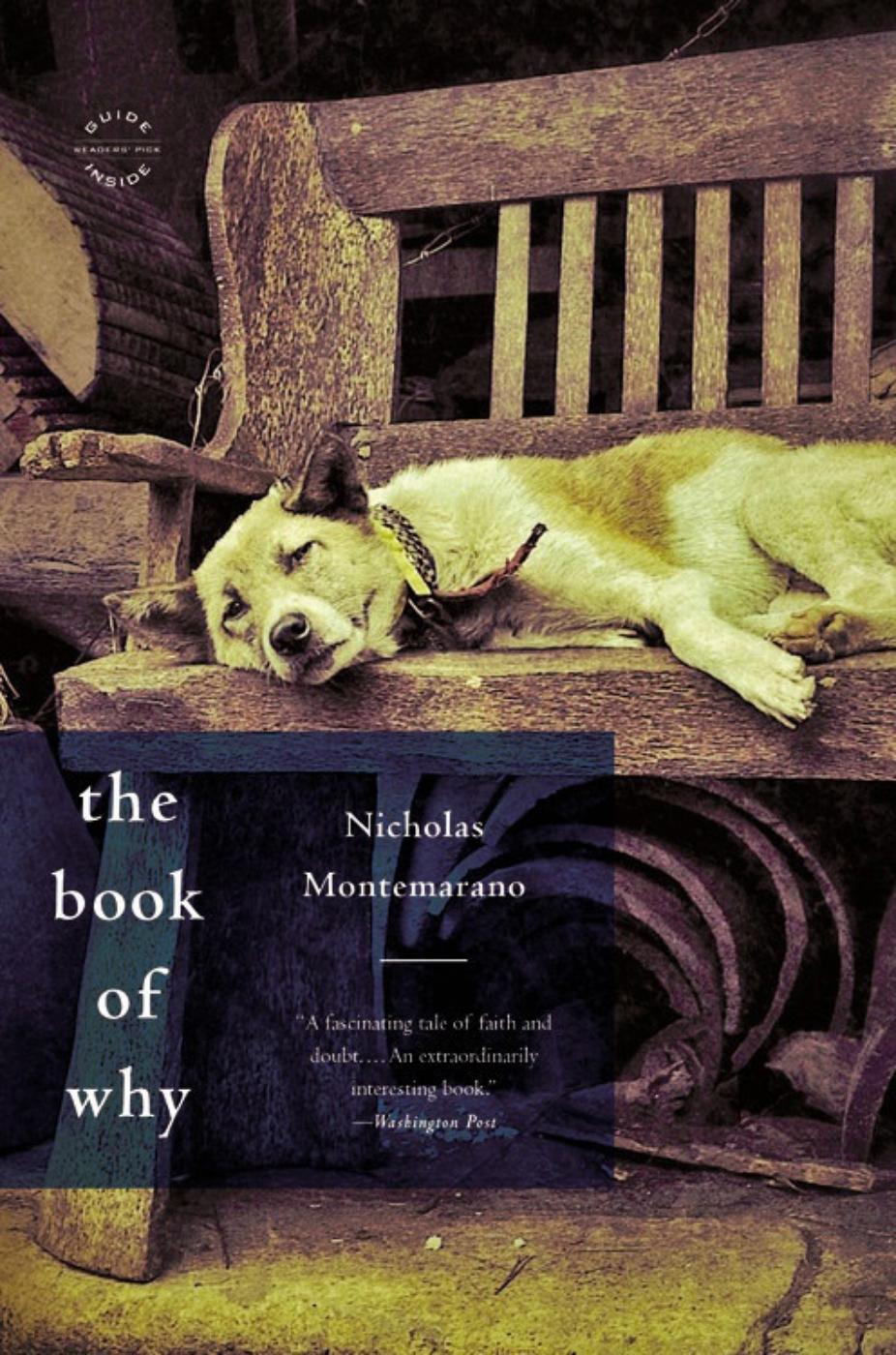

I have the dog, tooâa long-haired German shepherd. She used to be hers, then ours, now mine, but I think of the dog, still, as ours. Twelve years old a month ago, on Valentine's Day.

Hello is the beginning and goodbye the end of every story, the refrain tells me. First and last wordsâhers to me and mine to her. Unless you count the many times every day that I speak to herâsometimes in my head, but more often aloud. I can do that. Now that I live in Chilmark year round, I don't see other people very often. Every few months a ferry, then a long drive to see my mother in Queens. Otherwise, my life is solitary. There's Ralph, of course, and she counts as company. She wakes me with her nose each morning and waits for me to say hello, which is the word I greet her with, and then I allow her up on the bed, only her front paws, and scratch her ears until she moans, and then the dayâthis happens every day, and there's some comfort in thisâbegins. She follows me from room to room, but spends most of the day sleeping, twitching her way through dreams, unless I take her with me to town or to the beach to play fetch. When I drive or walk to the market, I wear a baseball hat; I don't want people to recognize me, though I suppose by now they might not.

It could be you here, singing, if it weren't for the fact that I know this recording so well by now, every note and pause and breath. I listen closely, but it never changes. I roll a tennis ball across the floor and Ralph brings it back to me. She holds it in her mouth, tail wagging. When I reach, she moves her head. A game we've played since she was a puppy. I point to my lap, she comes closer. I point to my lap again, she drops the ball. When I try to roll it past her again, she plays goalie and stops it with her front paws, crushes the ball between her jaws.

Enough with the ball; I want her close. She lies on my lap, and I close my eyes and pet her face, rub her belly, put my hand by her mouth to feel her panting, and you might be in the next room singing.

The song suddenly ends. I'm never prepared for this silence. Except I hear a voice, a woman saying hello, a knock at my door. I'm not sure how anyone could have gotten here. More than a few times, even in weather not as inclement as today's, I've had to abandon my car on the steep dirt road leading to the house. This happened on our honeymoon. Our shoes stuck in mud three inches deep, we walked the rest of the way up barefoot. I had to carry Ralph, who was still a puppy but getting heavy, maybe thirty-five pounds. It wasn't yet our home, just a house we rented. We talked, after our honeymoon, about how much we'd love to own the house, and by the following year we did. I might have said then that I'd intended it: I tacked photos of the house on the corkboard above my desk; I ordered address labels; on the first of each month I mailed myself a letter here.

Before I look out the window, I wonder what I'll do if no one's there, if I'm hearing things. I used to be afraid of ghosts when I was a boy, but for the past five years I've wanted to see one. Any ghost would do, would provide a kind of answer, but one in particular would be most welcome, no offense to the others out there, including my father. That is, if there are such things. I'm not sure if I believe in literal ghosts. Spirits, phantasms, apparitions. I certainly do believe in ghosts if you mean things that haunt youâmemories, feelings, regrets.

I'm disappointed to see that there really is a woman at my door. She appears solid, flesh and blood. Literally, I see bloodârunning from her nose and staining the tissue she's holding. She's pressing her other arm against her stomach as if she's wearing a sling, though she's not. I fear a scam of some sortâa robbery, a man with her, perhaps hiding behind my ice-covered carâbut I quickly change my thoughts lest they become reality. Some old habits never die. I have to shoulder the storm door three times before the ice gives, then I gesture for her to step back so that the door, which opens with my next push, doesn't further injure her.

She's tall, almost as tall as I am, and has long red hair. A face young and oldâdimples and crow's feet. Constellations of freckles on her forehead and nose. Blue eyes. Late thirties, I'm guessing, but probably gets proofed when she buys wine. She looks familiar, but then again, everyone looks familiar to me. She's smiling but sniffling. I can't tell if she's laughing or crying.

“I'm sorry to bother you,” she says. “My car is stuck down the road. I can't move my wrist. And my noseâmaybe it's broken, I don't know.”

“Come in,” I say, and I can see now that she

is

crying but trying to laugh.

I pull out a kitchen chair and she sits, though not comfortably. She seems concerned about the blood dripping on the floor. “Don't worry about that,” I tell her.

“I'm lost,” she says.

Ralph walks over to her, sniffs her jeans, her boots, rests her head on the woman's lap. “Sorry, sweetie,” she says. “I don't have a hand to pet you with.”

I give her a towel and try to take the bloody tissue, but she won't let me; she balls it and lays it on her lap, where Ralph sniffs it.

“I'm not sure you should put your head back,” I tell her. “I think it's one of those things we're taught that's really not true.”

“God, it won't stop,” she says.

“It doesn't look broken,” I say.

“The bump's mine,” she says. “My father gave it to me.”

I tear off a piece of clean tissue and give her the wad. “Try putting this in your nostril.”

She pushes the tissue in, and her eyes water.

“Now pinch the bridgeâsomewhere in the middleâand hold it.”

As she does, she winces. “Not too hard,” I tell her.

The tissue in her nostril is soaked with blood. Gently, I pull the tissue from her nose, then quickly wad the clean half and push it into her nostril.

“I'm Sam,” she says. “Sam Leslie.” She reaches out her left hand and I shake it. “Weird,” she says. “Doing that with my

left

hand.”

“Harry,” I say.

“I'm really sorry about this,” she says.

“Was there an accident?”

“I don't believe in accidents.”

“But something happened with your car.”

“Lost control coming up the hill and hit a tree. But the nose happened afterâI pretty much fell on my face.”

“Do you need another tissue?”

“I don't think so. Hey,” she says, “do you think I can let go now?”

“Probably been long enough.”

She releases her nose, then reaches into her back pocket and pulls out a piece of paper. “I was trying to find someone,” she says. “The address is 95 Old Farm Road.”

“You must be freezing.”

“Some guy at the market told me left after the chocolate shop. It was all ice.”

“Can I make you some tea?”

“Yes, thank you. And if you have some ice, for my wrist.”

The ice tray is empty. I go outside with a knife and chip some from inside an empty flower pot. Telephone wires sag close to the ground. Trees, some almost ready to bud, sparkle in the last light of day. I bring Sam a few chunks of ice wrapped in a washcloth.

Ralph lies on her back, presents her white belly. “Now I can say hello,” Sam says, and pets the dog.

“Ralph likes you. Then again, she likes everyone.”

“A girl Ralph?”

“Picked the name first, and she happened to be a she.”

“She doesn't seem to care.”

“I'd offer you my phone, but the lines are down.”

“I'm not sure who I'd call.”

“What about the person you're looking for?”

“I don't know him.”

“You don't

look

like a stalker.”

She laughs, rewraps the ice melting on her wrist. “I'd make a terrible stalker. I'd make a terrible almost anything.”

“So, what

do

you do?”

“I write obituaries,” she says. “God is my assignment editor.”

“Must be cheerful work.”

“It

is,

actually,” she says. “Let's not forget, these people are being remembered.”

“Yes, but for what?”

“More often for good than bad,” she says. “But you'd be surprised how many people have secrets.”

The teakettle whistles. I pour hot water over two tea bags. I place her cup of tea on the table beside her.

An icicle breaks from the tree near the window and shatters on the walkway. “So,” she says, “am I anywhere near Old Farm Road?”

“I don't know.”

“Well, if you live here and

you

don't know.”

“Some streets don't even have signs.”

The sun has set, so I turn on a few lamps. “I didn't realize how late it was,” she says. “Do you know a place where I can stay?”

“Plenty of places down-island, but I'm not sure how you'd get there.”

“Anything walking distance?”

“You'd have to crawl.”

“Not quite what I planned,” she says.

I try to think of a solution, but there isn't one, or rather, there's only one. “You could stay here.”

“That's nice of you,” she says, “but I don't know.”

A loud crack outside frightens the dog, who runs in circles, tail between her legs. I look out the window. A tree limb has fallen onto the front porch and now blocks the door.

“Maybe that's a sign,” she says. She thinks about it for a moment. “Let me make a call first, okay.”

“Phone's down.”

She takes a cell phone out of her pocket. “I'm still getting service.” She presses a few buttons on her phone.

“Would you mind telling me your full name and address?” she says.

“Harry Weiss, 122 Woods Road.”

Her call goes through on the third try. She says, “This is Sam Leslie. March 14, 2008. I'm in Martha's Vineyard. There's an ice storm, and I had a mishap with the car. Bloody nose, sprained wrist, could be worse. Staying at 122 Woods Road with a man named Harry Weiss. He's six-something, thin build, brown hair, beard, fortyish, has a German shepherd.”

She closes her phone, puts it back in her pocket. “No offense,” she says. “It's not that I don't trust you.”

“Neither Ralph nor I take offense.”

She sips her tea. “I was just thinking,” she says. “The man I'm looking forâmaybe you know him.”

“I doubt it.”

“He disappeared five years ago.”

“So he's missing.”

“No,” she says.

She leaves the washcloth on the table, walks across the room. She squats in front of my bookcase. “Hey, look at this!” She holds up the book so I can see. “This is him. I'm telling youâthis is a sign.”

“What does he look like?”

“Not sure,” she says. “None of his books has an author photo.”

“I haven't opened that book in years,” I say.

She starts flipping through the book, but I walk over and take it from her. “I'm sorry, but I probably wrote some personal things in the margins.”

“I do the same,” she says. “But hey, don't you think this is a sign? That I'm looking for him and I end up here and I find his book on your shelf?”

“It was a bestseller,” I say. “You could probably find it in many homes.”

“True,” she says. “But that's not what he would say.”

“How do

you

know?”

“Because I've read all his books.”

“I mean, how do you know what he would say

now

?

”

“I don't,” she says. “That's another reason to find him.”

“So, you don't believe in coincidence.”

“Do you know who Paul Winchell is?”

“No.”

“He was the voice of Tigger in

Winnie the Pooh

,

” she says. “He was also the first person to patent an artificial heart, assisted by Dr. Henry Heimlichâyes,

that

Heimlich. I have too much information inside my head, I'm telling you. The point is, Paul Winchell died one day before John Fiedler, who was the voice of Piglet.”

“And this means⦔

“Lawrence Welk's trumpeter and accordion player died on the same day.”

“Tragic,” I say.

“Jim Henson and Sammy Davis, Jr.,” she says. “Orville Wright and Gandhi. Antonioni and Bergman.”

“If enough people die on any given day⦔

“Adams and Jefferson,” she says. “On the Fourth of July.”

“Coincidence,” I tell her.

“I don't think so,” she says.

“You don't sound sure.”

She touches her nose, checks her finger for blood. “Something too easy to believe isn't worth believing.”

“I'm not sure you'd make it as a preacher.”

“The best preachers express the most doubt,” she says. She unties her boots with her uninjured hand, kicks them off. “I've made a mess of your floor.”

“Ralph has done worse.”

The dog is sleeping by the door; her ears stand up at the sound of her name, but she doesn't open her eyes.

“Hey, what do

you

do?”