Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (21 page)

It was hard to sit still. The cold was ten times worse the moment she stopped moving, and the darkness was gathering itself. It settled around her, as solid as stone. Olive began to have the feeling that she wouldn’t be able to move if she tried.

“Olive,” said a voice. It was no longer a whisper. Now it was a low, solid voice—a man’s voice. It sounded like rocks grinding against one another in a very deep, dark hole. “Olive, come with me.”

Olive’s foot twitched. “No,” she whispered.

“Come here,” commanded the voice.

Both of Olive’s feet made a little shuffling step. “No,” Olive said, more loudly this time. “I’m not going to go with you and let you push me out a window.”

In the darkness behind her, a man laughed. “Very well. I simply thought you would want to get away from those spiders.”

She felt them first on her ankles, and then on her calves, and then everywhere on her body: hundreds of running legs—legs skittering and crawling and climbing all over her. Olive squeezed her eyes shut. If she screamed, they would go into her mouth. More than anything, she wanted to turn on the lantern and prove that the spiders were only a trick, but if she did, her whole plan would be spoiled. It was her last chance.

This isn’t real,

Olive told herself.

This isn’t real this isn’t real this isn’t real.

Olive told herself.

This isn’t real this isn’t real this isn’t real.

All at once, the tickling, crawling legs were gone. Olive took a deep breath.

“You’re a brave girl, Olive,” said the voice. “That’s one of your few good qualities, isn’t it?”

Olive’s stomach gave a sick little lurch.

The voice went on, lower, closer. “Your parents will wonder where you’ve gone. For a while, that is. Eventually they’ll move on. Perhaps they will have another child. One that is more . . . what they had hoped for.” The voice sighed. “I know—children can be such a terrible disappointment sometimes.”

Olive forced her voice out of her throat. “They wouldn’t forget me. They’d look for me.”

“But is there anyone else who will?” the voice rumbled against Olive’s neck. When she turned around, no one was there. The voice went on. “Is there anyone else, in all the world, who will truly miss you when you’re gone?”

“M—Morton will miss me,” Olive stammered.

“Morton would have gone with anyone who let him out of that painting.” The voice chuckled mirthlessly. “If he had had a choice, it wouldn’t have been you.”

“The cats . . .” whispered Olive.

“Ah, the cats. The cats just want to be rid of me, to be quite frank,” said the voice, which now seemed to be coming from behind Olive’s knees. “Once all of this is over, they’ll forget about you more quickly than your old schoolmates have.”

Olive could barely breathe. “How do you know about that?” Her voice was a tiny wisp in the icy air.

The voice laughed again. “At all of those schools you’ve left, no one is saying, ‘Where is that Olive Dunwoody? ’ They forgot your name long ago. Some of them never knew it at all. Most haven’t even noticed that you’re gone.”

The darkness was getting inside of her. Olive could feel it. It had seeped in through her eyes, and her ears, and her skin, and now everything inside of her was dark. The world was just as dark and empty, full of holes left by people she didn’t even know. Darkness was all that was left. Darkness, and some tiny thing she was trying to remember, but it kept slipping away from her grasp, like a floating dandelion seed.

“Ask yourself, Olive: Who would notice? Who would care if you just . . . disappeared?”

A small, warm breeze stirred the frigid air, and Olive knew the tiny attic window was open. “What lovely moonlight,” said the voice. “Just enough light to look at these paintings. They are all still there, you know. Come and see.” Olive heard the soft clack of canvases falling against each other, and knew that the thing—Aldous McMartin, or whatever it was—was flipping through the stack of paintings where she had once found Baltus. “I would even let you choose, Olive. You can decide for yourself which painting you would like to be inside. Or I could paint something new, especially for you.” The voice dropped to a whisper. “You’ve already imagined it, haven’t you, Olive? Sometimes you would rather be in a painting than face the real world, wouldn’t you?”

Olive didn’t answer. Couldn’t answer. But way down in the farthest, darkest corner of her mind, a tiny voice whispered

Yes.

Yes.

Air like the blast from an open freezer settled on her face. Olive closed her eyes, letting the darkness come closer. It pushed the floating dandelion seed out of her reach. Maybe she should stop fighting, stop trying to remember.

The frost on her eyelashes was turning to heavy crystals of ice. Her clothes were like stones, solid and heavy. She felt so sleepy. The darkness inside her eyelids was much warmer and friendlier than the darkness in the attic. She could rest. She could just go to sleep, and it would all be over.

“Very well. I will decide for you,” the voice whispered in her ear. It was almost gentle, like someone tucking her into bed at night. “Then you will truly belong here, in this house, forever. And no one will ever make you feel out of place again.” The words wrapped around Olive, warm and heavy. They pulled her down toward the bottom of the darkness. “Go to sleep, Olive. You won’t need to feel a thing. No more fear. No more loneliness. Nothing at all.”

The last wisps of the world faded away. Olive felt as numb as her toes. Numb to cold, to fear, to everything. Her heart was one big empty room, and its emptiness echoed with the things that were missing. She had never noticed how much she had been keeping in there until it was all gone.

In that big blank darkness, the thing she had been trying to catch, the thing that had been floating through her mind like a dandelion seed, suddenly came to rest. And it wasn’t a dandelion seed at all. It was a tiny, flickering light—the light from a candle your mother hands you. The light of a flashlight against a dark sky.

Olive could almost feel the hands on top of hers: her mother’s, her father’s, Morton’s small warm palm, the fur-tufted paws of three cats. They were all there, inside of her, as she pushed the button on the camping lantern.

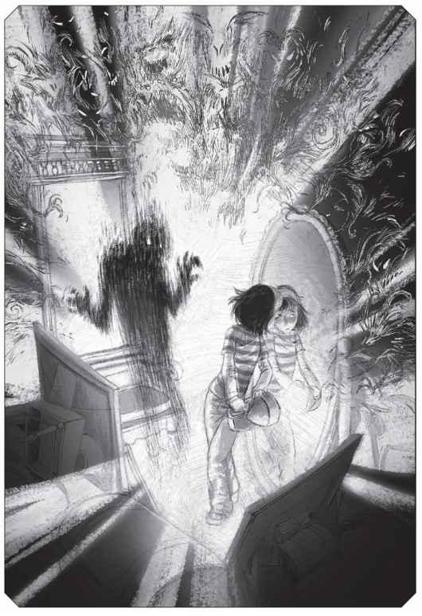

The sudden brilliance of fluorescent light exploded the darkness. The light was reflected by the ring of mirrors that Olive had moved into place, its beams multiplying, glancing in all directions, building a cage of brightness around Olive and the thing that stood next to her. Squinting, Olive could just make out the figure from Mr. McMartin’s self-portrait—something dark, gaunt, and twisted, something barely human—trapped inside the circle of light. In the shadow that should have been its face, Olive could see two spots reflecting the light—two eyes that looked right into hers. But he couldn’t scare her anymore. The light was erasing Aldous McMartin. Brightness ate away his feet, his legs, his long, knobby fingers, his skeletal jaw. When only a mouth and eyes were left, he let out a roar that echoed inside the attic, shaking the dust from the walls, rattling out through the old gray stones. And then every trace of him was gone.

23

O

LIVE BLINKED, LETTING her aching eyes adjust.

LIVE BLINKED, LETTING her aching eyes adjust.

The attic was quiet. It was not the ominous quiet that tells you something is sneaking up behind you, but a peaceful quiet—the kind of quiet that makes you want to curl up and sleep. There were still shadows in the corners, of course, but they thinned and shifted harmlessly as Olive stood up, lifting the lantern. She could feel the air growing warmer.

With the lantern in one hand, Olive stumbled exhaustedly down the attic stairs. The door swung open on the first try. The lantern’s bright beams fell over Morton and the cats, who huddled together in the entryway, all of them squinting into the light. For a moment, no one moved.

“Olive?” Morton whispered.

Olive took a deep breath. “He’s gone.”

Horatio and Leopold let out yowls of joy. Morton hopped up and down while holding on to Olive’s arm, his round white head bobbing like a helium balloon on a string. Harvey rocketed from wall to wall above them, whooping, “Youdidityoudidityoudidit!” between fits of laughter.

Leopold was the first to collect himself. “Miss,” he proclaimed, “your household thanks you. Your courage and cunning in battle have—” But here Leopold was interrupted by Harvey landing on his head.

Horatio gazed up at Olive as Leopold and Harvey rolled through the picture frame and into the pink room in a hissing, chortling ball. Then Horatio smiled. And it was an actual smile, without a trace of sarcasm in it. “I can’t believe it,” he said. “You did it. You really did it.” Olive reached down to scratch Horatio gently between the ears.

Morton threw his spindly arms around Olive’s ribs, still jumping up and down. “I’m going to tell everybody on the whole street about you!”

Looking down at his tufty head, Olive felt her smile waver. A lump began to form in her throat, but a stubborn yawn pushed it away. “Let’s go get some sleep,” she said.

Olive grabbed Horatio’s tail and held on to Morton. The three of them trooped out into the hallway, where all the paintings were back in their frames, and all the lights had turned back on.

They stopped in front of the painting of Linden Street. The picture was different now. The sky was a softer, warmer shade of dusk, and a few stars twinkled at the edge of the frame. The mist that had smothered the field had thinned to a few decorative wisps. In the distant houses, Olive spotted the glimmer of cheerful lights.

Olive cleared her throat. “I guess—I guess this didn’t really help you,” she said, looking everywhere but at Morton. “I mean, it won’t help you get back home. To your

real

home.”

real

home.”

Morton was quiet.

Olive forced out the next words. “Morton, I don’t know how to help you. I can’t make what happened to you

not

have happened.”

not

have happened.”

“I know,” Morton said softly.

“I’ll keep trying, though,” Olive promised. “Maybe someday . . .” She trailed off. There were no words to finish that sentence.

“Olive?” said Morton. “That light is hurting me.”

“Oh. I’m sorry.” Olive turned off the camping lantern. Morton cautiously rubbed his arm, where it had been closest to the bright light. For a moment, neither of them spoke.

“I’ll come visit you, though,” Olive said at last. “I mean, if you want me to. And if the cats will bring me.”

Horatio rolled his eyes in a beleaguered sort of way, then nodded.

“I want you to,” said Morton. “That would be fun.”

“Morton,” said Olive, leaning her forehead against the wall so that Morton couldn’t see it if she started to cry, “I’m sorry.”

Morton shrugged. “It’s all right,” he said, trying very hard to smooth the quaver out of his voice. “Maybe . . .” Morton blinked hard. “Maybe it will be different now. In there.”

“Out here, too,” said Olive. They looked at each other for a moment before Olive turned away.

“Leopold, would you help Morton get home?” Olive called as the yowling ball of cats rolled back into the hall. Leopold extracted himself from Harvey’s grip, gave Olive a salute, and offered Morton his tail.

“Godspeed, Sir Pillowcase!” cried Harvey to Morton with a knightly wave as Leopold and Morton slipped through the frame.

Olive let out a deep breath. Then she scuffled into her own bedroom and flopped down next to Hershel in a pile of fluffy pillows and soft, warm blankets. Before she could think another thought, she had fallen asleep.

24

W

E’RE HOME!” CALLED Mr. Dunwoody cheerily from the front door.

E’RE HOME!” CALLED Mr. Dunwoody cheerily from the front door.

Olive looked up from a massive breakfast of hot cocoa, bananas, Mrs. Nivens’s cookies, and pink kittens with marshmallows. Mrs. Dunwoody swept down the hall to the kitchen and gave Olive a kiss on the forehead.

“How was the conference?” Olive asked.

“It was illuminating,” said Mr. Dunwoody, setting down the suitcases. “We brought you something.” With a flourish, he unfolded a T-shirt printed with a chicken and held it up for Olive to see.

“‘Why did the chicken cross the Möbius strip?’” Olive read aloud. Mr. Dunwoody turned the shirt around to the back. “‘To get to the same side.’”

Other books

Blood Games by Richard Laymon

Cowboys Down by Barbara Elsborg

Just Different Devils by Jinx Schwartz

The Memory Box by Eva Lesko Natiello

Winterlong by Elizabeth Hand

Patient Darkness: Brooding City Series Book 2 by Shutt, Tom

The Enchanted Rose by Konstanz Silverbow

Working the Dead Beat by Sandra Martin

Private Lies by Warren Adler

La tierra silenciada by Graham Joyce