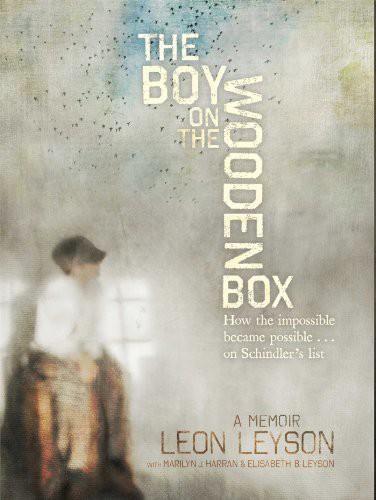

The Boy on the Wooden Box

To my brothers, Tsalig and Hershel, and to all the sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, parents and grandparents who perished in the Holocaust.

And

to Oskar Schindler, whose noble actions did indeed save a “world entire.”

—Leon Leyson

I HAVE TO ADMIT, MY palms were sweaty and my stomach was churning. I had been waiting in line patiently, but that didn’t mean I wasn’t nervous. It was my turn next to shake the hand of the man who had saved my life many times . . . but that was years ago. Now I wondered if he would even recognize me.

Earlier that day in autumn 1965, on my way to the Los Angeles airport, I told myself that the man I was about to meet might not remember me. It had been two decades since I had seen him, and that meeting had been on another continent and under vastly different circumstances. I had been a scrawny, starving boy of fifteen who was the size of a ten-year-old. Now I was a grown man of thirty-five. I was married, a US citizen, an army veteran, and a teacher. As others moved forward to greet our

guest, I stayed behind in the background. After all, I was the youngest of our group, and it was only right that those who were older should go ahead of me. To be honest, I wanted to postpone as long as I could my disappointment if the man to whom I owed so much didn’t remember me.

Instead of disappointed, I felt elated, warmed by his smile and his words: “I know who you are!” he said with a glint in his eye. “You’re ‘little Leyson.’ ”

I should have known Oskar Schindler would never disappoint me.

On that day of our reunion, the world still didn’t know of Oskar Schindler nor of his heroism during the Second World War. But those of us at the airport knew. All of us, and over a thousand others, owed our lives to him. We survived the Holocaust because of the enormous risks Schindler took and the bribes and backroom deals he brokered to keep us, his Jewish workers, safe from the gas chambers of Auschwitz. He used his mind, his heart, his incredible street smarts, and his fortune to save our lives. He outwitted the Nazis by claiming we were essential

to the war effort even though he knew that many of us, myself included, had no useful skills at all. In fact, only by standing on a wooden box could I reach the controls of the machine I was assigned to operate. That box gave me a chance to look useful, to stay alive.

I am an unlikely survivor of the Holocaust. I had so much going against me and almost nothing going for me. I was just a boy; I had no connections; I had no skills. But I had one factor in my favor that trumped everything else: Oskar Schindler thought my life had value. He thought I was worth saving, even when giving me a chance to live put his own life in peril. Now it’s my turn to do what I can for him, to tell about the Oskar Schindler I knew. My hope is that he will become part of your memory, even as I was always a part of his. This is also the story of my life and how it intersected with his. Along the way I will introduce my family. They, also, endangered their lives to save mine. Even in the worst of times, they made me feel I was loved and that my life mattered. In my eyes, they are heroes too.

I RAN BAREFOOT ACROSS THE Meadow toward the river. Once among the trees, I flung off my clothes, grabbed my favorite low-hanging branch, swung out across the river, and let go.

A perfect landing!

Floating along in the water, I heard one splash and then another as two of my friends joined me. Soon we climbed out of the river and raced back to our favorite branches to start all over again. When lumberjacks working upstream threatened to spoil our fun by sending their freshly cut

trees downstream to the mill, we adapted quickly, opting to lie on our backs, each on a separate log, gazing at the sunlight breaking through the canopy of oak, spruce, and pines.

No matter how many times we repeated these routines, I never tired of them. Sometimes on those hot summer days, we wore swim trunks, at least if we thought any adults might be around. Mostly we wore nothing.

What made the escapades even more exciting was that my mother had forbidden my going to the river.

After all, I didn’t know how to swim.

In winter the river was just as much fun. My older brother Tsalig helped me create ice skates from all kinds of unlikely materials, metal remnants retrieved from our grandfather the blacksmith and bits of wood from the firewood pile. We were inventive in crafting our skates. They were primitive and clumsy, but they worked! I was small yet fast; I loved racing with the bigger boys across the bumpy ice. One time David, another of my brothers, skated on thin ice that gave way. He fell into the freezing

river. Luckily, it was shallow water. I helped him out and we hurried home to change our dripping clothes and thaw out by the hearth. Once we were warm and dry, back we raced to the river for another adventure.

Life seemed an endless, carefree journey.

So not even the scariest of fairy tales could have prepared me for the monsters I would confront just a few years later, the narrow escapes I would experience, or the hero, disguised as a monster himself, who would save my life. My first years gave no warning of what was to come.

My given name is Leib Lejzon, although now I am known as Leon Leyson. I was born in Narewka, a rural village in northeastern Poland, near Białystok, not far from the border with Belarus. My ancestors had lived there for generations; in fact, for more than two hundred years.

My parents were honest, hardworking people who never expected anything they did not earn. My mother, Chanah, was the youngest of five children, two daughters and three sons. Her older sister was called Shaina, which in Yiddish means “beautiful.” My aunt was indeed

beautiful; my mother wasn’t, and that fact informed the way everyone treated them, including their own parents. Their parents certainly loved both their daughters, but Shaina was regarded as too beautiful to do physical labor, while my mother was not. I remember my mother telling me about having to haul buckets of water to the workers in the fields. It was hot; the water was heavy, but the task turned out to be fortuitous for her—and for me. It was in these fields my mother first caught the eye of her future husband.

Even though my father initiated their courtship, their marriage had to be arranged by their parents, or at least seem to be. That was the accepted custom in eastern Europe at the time. Fortunately, both sets of parents were pleased with their children’s mutual attraction. Soon the couple married; my mother was sixteen and my father, Moshe, was eighteen.

For my mother, married life was in many ways similar to how her life had been with her parents. Her days were spent doing housework, cooking, and caring for her family,

but instead of her parents and siblings, she now looked after her husband and soon their children.

As the youngest of five children, I didn’t have my mother to myself very often, so one of my favorite times was when my brothers and sister were at school and our women neighbors came to visit. They would sit around the hearth, knitting or making pillows from goose feathers. I watched as the women gathered the feathers and stuffed them into the pillowcases just so, gently shaking them so they spread evenly. Inevitably, some of the down would escape. My job was to retrieve the little feathers that wafted through the air like snowflakes. I reached for them, but they would float away. Now and then, I’d get lucky and catch a handful, and the women would reward my efforts with laughter and applause. Plucking geese was hard work, so every single feather was precious.

I looked forward to listening to my mother swap stories and sometimes a bit of local village gossip with her friends. I saw a different, more peaceful and relaxed side of her then.

Busy as my mother was, she always had time to show her love. She sang with us children, and, of course, she made sure we did our homework. Once I was sitting by myself at the table, studying arithmetic, when I heard a rustling behind me. I had been so focused on what I was learning that I hadn’t heard my mother come in and begin cooking. It wasn’t mealtime, so that was surprising. Then she handed me a plate of scrambled eggs, made just for me. She said, “You are such a good boy, you deserve a special treat.” I still feel the pride that welled up within me at that moment. I had made my mother proud.

My father had always been determined to provide a good life for us. He saw a better future in factory work than in his family’s trade of blacksmithing. Shortly after marrying, he began working as an apprentice machinist in a small factory that produced handblown glass bottles of all sizes. There my father learned how to make the molds for the bottles. Thanks to his hard work, his innate ability, and his sheer determination, he was frequently promoted. One time the factory owner selected my father to attend

an advanced course in tool design in the nearby city of Białystok. I knew it was an important opportunity because he bought a new jacket especially for the occasion. Buying new clothes was something that didn’t happen very often in our family.

The glass factory prospered, and the owner decided to expand the business by moving it to Kraków, a thriving city about three hundred fifty miles southwest of Narewka. This caused a great deal of excitement in our village. In those days it was rare for young people

,

really for anyone, to leave the town of their birth. My father was one of the few employees to move with the factory. The plan was for my father to go first. When he had enough money, he would bring all of us to Kraków. It took him several years to save that much and to find a suitable place for us to live. In the meantime, my father returned every six months or so to see us.