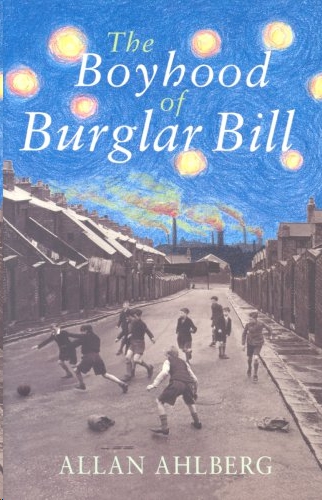

The Boyhood of Burglar Bill

Read The Boyhood of Burglar Bill Online

Authors: Allan Ahlberg

The Boyhood of Burglar Bill

– a work of fiction – is the second in a sequence of stories in which Allan Ahlberg explores his own childhood.

My Brother’s Ghost

, shortlisted for the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize, was the first.

On winter nights the gravestones glowed

In streetlamp shine on Cemetery Road.

When coming home my heart would beat

From footsteps that were not my feet.

On frosty evenings scared to death

By breathing that was not my breath.

Until at times I’d quite explode

And run for my life down Cemetery Road.

The Mysteries of Zigomar

(1997)

Also by Allan Ahlberg

Each Peach Pear Plum

Peepo!

Burglar Bill

The Jolly Postman

It was a Dark and Stormy Night

Please Mrs Butler

Heard it in the Playground

Friendly Matches

Woof!

The Boy, the Wolf, the Sheep and the Lettuce

My Brother’s Ghost

ALLAN AHLBERG

PUFFIN

PUFFIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published 2007

Published in this edition 2008

1

Copyright © Allan Ahlberg, 2007

An excerpt from the poem ‘Cemetery Road’ from

The Mysteries of Zigomar

by Allan Ahlberg,

published by Walker Books in 1997, has been reproduced by kind permission of the publisher.

The excerpts on pages 122 and 167 are taken from

The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren

by Iona and

Peter Opie, published by Oxford University Press in 1959.

Reproduced here by kind permission of Iona Opie.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holder of the poem by Frances Cornford on

page 128

.

The publisher would welcome any further information.

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not,

by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the piublisher’s

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191353-7

THE PLAYERS

| Boys | Girls |

| Spencer Sorrell | Edna May Prosser |

| Ronnie Horsfield | Brenda Bissell |

| Tommy Ice Cream | Monica Copper |

| Tommy Pye | |

| Joey Skidmore | |

| Trevor Darby | Teachers |

| Malcolm Prosser | Mr Cork |

| Patrick Prosser | Mr Reynolds |

| Graham Glue | Miss Palmer |

| Arthur Toomey | Mrs Belcher |

| Wyatt | Mrs Harris |

| Other Boys | Barbers |

| Amos | Mr Cotterill |

| Vincent Loveridge | |

| Dogs | Dignitaries |

| Archie | Alderman and Mrs Haywood |

| Dinah | |

| Rufus | |

| Sadie and six pups, including Ramona |

Plus assorted parents, shopkeepers, park-keepers, bus conductors, referees and linesmen, not forgetting Mrs Moore, old man Cutler, Ray Barlow himself, too many Toomeys. Oh yes, of course, and me.

Part One

1

One-armed Man,

Three-legged Dog

The best and worst times of my life occurred, I truly believe, before I was twelve years old. It was another world in those days: terraced houses, wash houses, communal yards. Our lavatory was a brick-built gloomy box at the end of the garden. I got a good part of my education – world affairs, showbiz gossip – from torn squares of newspaper stuck out there on a nail behind the door. The streets were full of kids and empty of cars; the park, an orderly and enormous wilderness. Everything was urgent – vivid – outlined in fire at times. The world did not merely spin in those days, it went up and down like a roller-coaster.

Mr Cork was a madman. He had a wide flat face like a garden spade, and one arm. He often carried a cricket stump. If you didn’t know the answer to some question or other, he would hammer your

desk – bang! – and jump you out of your skin. He had this gravelly voice. ‘Ahlberg,’ he’d say. ‘C’mere.’ He was a teacher you see, supposed to be. Emergency-trained, for lion-taming, Joey Skidmore reckoned. There was a shortage of teachers after the war and more than a few of them had bits missing.

He was cunning too. You might think you knew it was coming, that cricket-stump trick, and grit your teeth determined

not

to jump. But he’d move on along the aisle, allowing some kid just time enough to breathe his sigh of relief, then quick dart back and – wallop! A heavy man he was, but light on his feet.

Mr Cork taught craft to the boys when the girls were having needlework with Miss Palmer. Also once a week on a Wednesday he’d march the boys, about sixty-six of us, out of the school gates, along Rood End Road, down Oldbury Road, across the Birmingham Road and into Guest, Keen & Nettlefold’s sports ground for football in the football season, cricket in the cricket. And that was how it started.

Sixty-six boys, more or less, two footballs, two sets of shirts, one madman and a whistle. This was how things were organized. Mr Cork took the first and second teams on the top pitch. It had goalposts, nets, even corner flags sometimes. They played a

proper match. Mr Cork, with his trousers tucked in his socks and his empty sleeve flapping, ran up and down kicking wildly at the ball from time to time, yelling at the kids. Coaching, he called it. This went on for a whole afternoon.

Meanwhile, down on the bottom pitch forty-four boys organized themselves into two warring factions and played their own game. No referee, no kit and pitch markings you could hardly see. It was like one of those historical events you get on TV where one half of a village tries to move a pumpkin or something up the hill and the other half tries to stop them. The groundsman stored his rollers along one side of this supposed pitch. There was a brook and a seasonal swamp behind one goal, scrap metal, huge coils of wire, containers full of toxic waste, I wouldn’t be surprised. But maybe I’m exaggerating.

The weather had little influence on Mr Cork. In wind and rain, snow and ice, if it was Wednesday we went. Mud never bothered him at all. (I wonder now though what

his

mother, or wife maybe, made of it.) Afterwards we’d troop back up the hill to school, kids peeling off when we passed their streets, like an army of zombies or

Flash Gordon and the Claymen

.

∗

One Wednesday, a dry and sunny day as it happened, the three of us – Spencer, Ronnie and me – left Mr Cork’s retreating column outside Milward’s. Ronnie picked up his gran’s copy of the local paper, Spencer bought a liquorice pipe. We stood around admiring the contents of Milward’s window.

‘Bags I that

Rupert

annual,’ Spencer said. ‘Bags I…’

Ronnie read the paper. There was a picture of a pools winner on the front page; the Mayor and Mayoress having tea in an old people’s home. And on the back an account of Oldbury Town’s latest fixture and an entrance form for the Coronation Cup.

‘Says here, the Cubs’ve gotta team up…’

Spencer peered over Ronnie’s shoulder.

‘… and the Boys’ Brigade.’

Spencer made no comment. He broke off a bit of his pipe and pushed it into Ronnie’s mouth. I stared at my reflection in the window, hair on end as usual like a cockatoo. Mrs Milward glared back at us and shooed us away. She judged we were up to something. Milward’s had more stuff pinched than they sold, according to her. I took a kick at a cigarette packet on the pavement; we moved off. On the allotments, old man Cutler in his off-white

painter’s overalls and his pork-pie hat was tending his bonfire, smoke billowing across the road.

‘We could get a team up,’ Spencer said.

The next morning in assembly Mr Reynolds talked to the whole school about boys peeing up the wall in the outside toilets, kids frothing up their milk with straws, kids kicking balls deliberately from the boys’ playground into the girls’ and infants’ playground, Jesus and the Coronation Cup. Rood End Primary would enter two teams, he said. The rest of us, he was sure, would want to come along and support the teams and, by implication, the entire royal family. Preliminary rounds would be played… the final was on… dates, times, places. Then, as Mrs Belcher struck up her ‘walking nicely music’ and we were leaving, Mr Reynolds saw fit to speak again.

‘Toomey – stop that. See me afterwards.’

‘Which one, Sir?’ said a voice.

‘Er… Brian.’

‘See all of ’em, Sir!’

‘Who said that?’

There were three Toomeys in the hall on that occasion; could have been four. Maurice Toomey was away working for his dad, or up at the juvenile court, more like.

At playtime Spencer and I played marbles with Joey Skidmore and lost. The Purnells’ three-legged dog, Archie, got under the gates and raced around the playground for a while, creating havoc. Archie was a wonder dog in all our eyes. Nearly a year ago he had got run over. They found his foot in the street but the rest of him ran off. Mr Purnell mourned for a while; Mrs Purnell offered to beat the motorcyclist up or at least wreck his bike. Then, lo and behold, a fortnight later back came Archie. Subsequently, he treated the Purnells with disdain, steered clear of traffic and was generally adopted by the neighbourhood. He could get a bone anywhere.

Lining up after playtime, Spencer and I compared our losses. Ronnie claimed to have been peeing up the outside-toilet walls in a competition organized by Amos. A ball came flying over the wall

from

the girls’ and infants’ playground, which raised a cheer. And Ronnie said, ‘We could y’know.’

‘What?’

‘What?’

‘Get a team up.’

2

The Coronation Cup

Mrs Glue peered suspiciously at us, the door open just enough to accommodate her head.

‘Graham’s out.’

‘But we’ve just seen him come in, Mrs Glue,’ said Spencer in his politest voice.