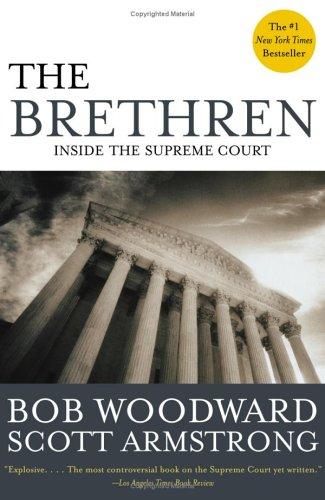

The Brethren

| Published: | 2005 |

| Tags: | Non Fiction Non Fictionttt |

SUMMARY:

The Brethren is the first detailed behind-the-scenes account of the Supreme Court in action. Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong have pierced its secrecy to give us an unprecedented view of the Chief and Associate Justices -- maneuvering, arguing, politicking, compromising and making decisions that affect every major area of American life.

"EXPLOSIVE

...

THE MOST CONTROVERSIAL BOOK ON THE SUPREME COURT YET WRITTEN"

Los Angeles Times Book Review

"A provocative book about a hallowed institution, the U.S. Supreme Court.... It is the most comprehensive inside story ever written of the most important court in the world. For this reason alone it is required reading."

Business Week

"It is to the credit of Woodward and Armstrong that they were willing—and able—to shatter this conspiracy of silence. It is certainly in the highest tradition of investigative journalism to expose the realities of institutions that affect our lives as greatly as the Supreme Court does."

Saturday Review

"Fascinating. The pace is swift, with details that rivet the attention."

Washington Post Book World

"One hell of a reporting achievement" Nat Hentoff,

Village Voice

"The year's best political book."

New York Post

Other

Avon books by

Bob Woodward

The Final Days

, with Carl Bernstein

The Brethren

I

NSIDE THE SUPREME COURT

Bob Wodward

ScottArmstrong

PUBLISHERS OF BARD, CAMELOT AND DISCUS BOOKS

AVON BOOKS

A division of

The Hearst Corporation

959

Eighth Avenue

New York, New York

10019

Copyright ©

1979

b

y Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong

Published by arrangement with Simon & Schuster,

a division of Gulf and Western Corporation

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number:

79-19955

ISBN:

0-380-52183-0

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster, a division of Gulf and Western Corporation,

1230

Avenue of the Americas, New York, New York

10020

First Avon Printing, January,

1981

The Simon & Schuster edition contains the following Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

.

Authors' Note

Two people labored as long and as hard on this book as the authors.Al Kamen, a former reporter for the

Rocky Mountain News,

assisted us in the reporting, writing and editing of this book. He was the chief negotiator and buffer between us. His thoroughness, skepticism and sense of fairness contributed immeasurably. No person has ever offered us as much intelligence, endurance, tact, patience and friendship.

Benjamin Weiser, now a reporter for

The Washington Post,

helped in the research, writing, editing and reporting. A devoted and resourceful assistant, no one could have been more loyal and trusted.

This book is as much theirs as ours.

Acknowle

dgments

This book has two sponsors, Benjamin C. Bradlee, the executive editor of

The Washington Post,

and Richard Snyder, president of Simon and Schuster. Without their support and encouragement this book would have been impossible. No other newspaper editor or book publisher would have been as willing to assume the risks inherent in a detailed examination of an independendent branch of government whose authority, traditions and protocols have put it beyond the reach of journalism.

At Simon and Schuster, we also owe special thanks to Sophie Sorkin, Frank Metz, Edward Schneider, Wayne Kirn, Gwen Edelman, Alberta Harbutt, Joni Evans, Harriet Ripinsky.

To Alice Mayhew, our editor, we give our respect and affection for her constant support and guidance as she nurtured this book to completion.

At

The Washington Post

we also thank Katharine Graham, Donald Graham, Howard Simons, the late Laurence Stern, Elizabeth Shelton, Julia Lee, Carol Leggett, Lucia New, Rita Buxbaum, Adam Dobrin.

A critical reading and numerous suggestions were provided by Karen De Young, Marc Lackritz, Ann Moore, Jim Moore, Bob Reich, Ronald Rotunda, Bob Wellen and Douglas Woodlock.

Tom Farber helped greatly with suggestions and writing.

Milt Benjamin, our colleague at the

Post,

devoted several months to recrafting, editing and rewriting the initial drafts. We will never be able to thank him enough.

We owe and give our greatest thanks to our sources.

Washington, D.C. August

1979

To Katharine Graham, Chairman of the Board, The Washington Post Company, for her unwavering commitment to an independent press

and the First Amendment. And to our children, Tali, Thane and Tracey.

Introduction Prologue

- TERM

- TERM

- TERM

- TERM

- TERM

- TERM

- TERM

- Index

Contents

Introduction

T

he

U

nited States S

upreme

Court

, the highest court in the land, is the final forum for appeal in the American judiciary. The Court has interpreted the Constitution and has decided the country's preeminent legal disputes for nearly two centuries. Virtually every issue of significance in American society eventually arrives at the Supreme Court. Its decisions ultimately affect the rights and freedom of every citizen—poor, rich, blacks, Indians, pregnant women, those accused of crime, those on death row, newspaper publishers, pornographers, environmentalists, businessmen, baseball players, prisoners and Presidents.

For those nearly two hundred years, the Court has made its decisions in absolute secrecy, handing down its judgments in formal written opinions. Only these opinions, final and unreviewable, are published. No American institution has so completely controlled the way it is viewed by the public. The Court's deliberative process—its internal debates, the tentative positions taken by the Justices, the preliminary votes, the various drafts of written opinions, the negotiations, confrontations, and compromises—is hidden from public view.

The Court has developed certain traditions and rules, largely unwritten, that are designed to preserve the secrecy of its deliberations. The few previous attempts to describe the Court's internal workings—biographies of particular Justices or histories of individual cases—have been published years, often decades, after the events, or have reflected the viewpoints of only a few Justices.

Much of recent history, notably the period that included the Vietnam war and the multiple scandals known as Watergate, suggests that the detailed steps of decision making, the often hidden motives of the decision makers, can

be as important as the eventual decisions themselves. Yet the Court, unlike the Congress and the Presidency, has by and large escaped public scrutiny. And because its members are not subject to periodic re

-

election, but are appointed for life, the Court is less disposed to allow its decision making to become public. Little is usually known about the Justices when they are appointed, and after taking office they limit their public exposure to the Court's published opinions and occasional, largely ceremonial, appearances.

The Brethren

is an account of the inner workings of the Supreme Court from

1969

to

1976

—the first seven years of Warren E. Burger's tenure as Chief Justice of the United States. To ensure that our inquiry would in no way interfere with the ongoing work of the Court, we limited our investigation to those years. We interviewed no one about any cases that reached the Court after

1976.

We chose to examine the contemporary Court in order to obtain fresh recollections, to deal with topical issues and to involve sitting Justices. This book is not intended as a comprehensive review of all the important decisions made during the period. The cases we examine generally reflect the interest, time and importance assigned to them by the Justices themselves. As a result, some cases of prominence or importance—but which provide no insight into the internal dynamics of the Court—have been dealt with only briefly or not at all. The Court conducts its business during an annual session called a

term,

which begins each October and continues until the last opinion is announced in June or early July. The Court recess runs from then until the next October.

Normally, there are seven decision-making steps in each case the Court takes.

- The decision to take the case requires that the Court note its jurisdiction or formally

grant cert.

Under the Court's procedures, the Justices have discretion in selecting which cases they will consider. Each year, they decide to hear fewer than two hundred of the five thousand cases that are filed. At least four of the nine Justices must vote to hear a case. These votes are cast in a secret conference attended only by the Justices, and the actual vote is ordinarily not disclosed.

2

Once the Court agrees to hear a case, it is scheduled for

written and oral argument

by the lawyers for the opposing sides. The written arguments, called legal briefs, are filed with the Court and are available to the public. The oral arguments are presented to the Justices publicly in the courtroom; a half-hour is usually allotted to each side.

3

A few days after oral arguments, the Justices discuss the case at a closed meeting called the

case conference.

There is a preliminary discussion and an initial vote is taken. Like all appellate courts, the Supreme Court normally uses the facts already developed from testimony and information presented to the lower trial court. The Supreme Court can reinterpret the laws, the U.S. Constitution, and prior cases. On this basis, the decisions of lower courts are affirmed or reversed. As in the cert conference, at which Justices decide which cases to hear, only the Justices attend the case conferences. (The nine members of the Court often refer to themselves collectively as the conference.)

4

The next crucial step is the selection of one of the nine Justices to write a majority opinion. By tradition, the Chief Justice, if he is in the initial majority, can

assign

himself or another member of the majority to write the opinion. When he is not in the majority, the senior Justice in the majority makes the assignment.

5

While one Justice is writing the majority opinion, others may also be drafting a

dissent

or a separate

concurrence.

It can be months before these opinions—a majority, dissent or concurrence—are sent out or circulated to the other Justices. In some cases, the majority opinion goes through dozens of drafts, as both the opinion and the reasoning may be changed to accommodate other members of a potential majority or to win over wavering Justices. As the Justices read the drafts, they may shift their votes from one opinion to another. On some occasions, what had initially appeared to be a majority vanishes and a dissenting opinion picks up enough votes to become the tentative majority opinion of the Court.

6

In the next to last stage, the Justices

join

a majority or a dissenting opinion. Justices often view the timing, the sequence and the explanations offered for

"joins"

as crucial to their efforts to put together and hold a majority.

7.

In announcing and publishing the final

opinion,

the Justices choose how much of their reasoning to make public. Only the final versions of these opinions are available in law libraries. The published majority opinion provides the legal precedents which guide future decisions by lower courts and the Supreme Court itself.

We began this project in the summer of

1977

as two laymen lacking a comprehensive knowledge of the law. We read as many of the cases and as much of the background material about the period as time would allow. We found the work of Derrick Bell, Paul Brest, Lyle Denniston, Fred Graham, Eugene Gressman, Gerald Gunther, Richard Kluger, Nathan Lewin, Anthony Lewis, John MacKenzie, Michael Meltsner, John Nowak, Ronald Rotunda, Nina Totenberg and Laurence Tribe particularly helpful. We thank them, and countless others on whose writings we have drawn.