The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (36 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

There we encountered a rather unpleasant surprise. When Dave, our anthropologist, had met Solo in San Augustín, he’d been much impressed with the guy’s purported knowledge of the forest. Dave later cabled him, inviting him to join us in Florencia for our expedition down the Río Putumayo, and Solo, it seemed, had accepted. This was problematic. That Terence and Ev had coupled up was news to Solo; he thought his former partner had gone to Peru. Nevertheless, he insisted he ought to accompany us, arguing that he was a man of the forest and that we wouldn’t find

oo-koo-hé

without him. Finally, Terence gave in. There was an unspoken tension between them from the start, but for a while, at least, an uneasy truce reigned. Solo was a screwball; he believed he’d been, at various times, the reincarnation of Hitler, Christ, and Lucifer, and that various famous personages inhabited the animals that traveled with him: his kitten, his monkey, and his dog. These creatures were vegetarians like Solo and hence appeared twisted and unhealthy, like Solo, whose teeth were rotting and who looked quite undernourished. Solo communicated with entities he called the Beings of Light, and even the most trivial decision could not be made without consulting with them; their decrees were expected to be obeyed not only by Solo but by everyone else in our party. It was pretty clear that this situation would become untenable in the very near future.

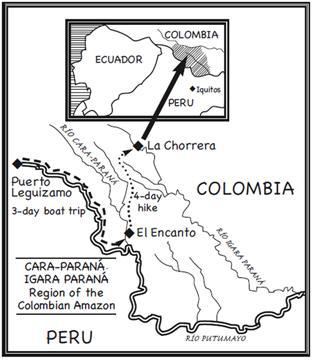

But for now the brotherhood was six, and after a short stay we moved on to Puerto Leguizamo, the jumping-off point for boats heading down the Putumayo toward Leticia and points east. The grim river town turned out to be singularly lacking in amenities or any kind of charm. Burroughs observed that the “place looks like it was left over from a receding flood” when he passed through in 1953, and apparently little had changed since then.

Puerto Leguizamo is memorable in this tale for two things. One was an American who had lived there for many years, John Brown, a black man and the son of a slave. He was ninety-three, he said, but he must have been older, and he had seen it all. He had left the United States in 1885, never to return. He’d traveled the Caribbean, eventually joining the merchant marine, visiting ports around the world before reaching Iquitos, Peru in about 1910. The Amazonian rubber boom and the atrocities inflicted on the indigenous people in the quest for “white gold” were then in full swing. As demand for latex grew in the outside world, Indians were forced into slave labor, driven to collect the substance from the forest, among other tasks, under the whips and guns of ruthless foremen. Thousands were raped, tortured, and murdered in a campaign of mass terror that decimated the area’s tribes.

John Brown found work with a company run by the notorious rubber baron Julio César Arana. Some implicated Brown in atrocities that were committed in Arana’s name, but according to an early account of that era written by Walter Hardenburg in 1913, Brown may have helped to expose those misdeeds. He cooperated with a Royal High Commission investigation organized by the Irish statesman and human-rights crusader Roger Casement, who as British counsel in Rio de Janeiro had traveled to Peru to document the violence.

Route map to La Chorrera. (Map by M. Odegard)

Brown visited La Chorrera for the first time in 1915. He told us about his experience there with ayahuasca, which he called

yagé

. Shortly after he’d taken it alone in the forest, a little man stepped out onto the trail in front of him and said, “I am

yagé

. If you come into the forest with me I will teach you everything there is to know.” Brown said he declined the invitation, but I had to wonder. In any case, though stooped with age he cut a most impressive figure. We were awed and intimidated. This man had witnessed and participated in so much of the turmoil that had marked the decades near the turn of the twentieth century. Under his ancient gaze, we felt like children, which we were; the oldest among us was twenty-four.

Puerto Leguizamo is also memorable as the site of our first encounter with

Psilocybe cubensis

, the psilocybin-containing mushroom that within a few weeks would replace

oo-koo-hé

as the central focus on our quest. During our stop in Florencia, Terence had found and consumed a single large specimen, but the rest of us weren’t so lucky. We had better luck in the pastures around Puerto Leguizamo. Though it hadn’t rained for some days, we found enough specimens to allow everyone to give it a try. Since we had nothing better to do, we collected a few of the beautiful carpophores and repaired to our casita at the primitive hostel where we were staying. Except for Terence’s low-dose bioassay in Florencia, none of us had ever taken mushrooms before; we identified them from the references we had brought. Back in Berkeley and Boulder, psilocybin and “magic mushrooms” were the stuff of legend but impossible to acquire through our networks. Magic mushrooms are now widely cultivated and relatively easy to find; many people are familiar with their effects. That was not the case when we took them at Puerto Leguizamo. We didn’t know what to expect.

We were pleasantly surprised. Psilocybin seemed a lot less “serious” than LSD, whose trip seemed more weighted with personal psychology and psychoanalytical baggage. Psilocybin had its own personality—an elfin, mischievous character. It stimulated laughter and plastered silly grins on our faces. With eyes open, colors were enhanced and there was an almost tactile, silken quality to the air. Closing my eyes resulted in seemingly effortless evocations of the most beautiful, coruscating visions, rich in violet and blue overtones, hard-edged, three-dimensional, and yet somehow organic and sensuous. Along with the visual effects were effects on cognition and language. Puns came easily; our conversation was threaded with merriment and cleverness, all spilling out spontaneously, with no apparent effort. At times it seemed that the mushrooms opened up a direct pipeline to the Logos itself, the bedrock of meaning that underlies all language, indeed, all of human cognition and understanding. At times you could almost see it, like an effervescent foam of meaning bubbling up through the interface between understanding and apprehension, a mercurial lubricant between what Henry Munn, writing in 1973, termed “the contact of the intention of articulation with the matter of experience.”

Yes, mushrooms made us laugh and we couldn’t stop smiling; but at a more profound level they seemed to enable us to gaze into the fabric of reality itself. They were easy on the body, no nausea or stomach cramps. And they were fun! The experience was non-threatening in every way. We had found the perfect recreational psychedelic. We had thought we had come in search of bigger fish than this, a misconception of which we would soon be disabused. But for now, the mushrooms would do. They would definitely do!

It was only a couple of days after this experience that we finally secured passage on the next leg of our journey. The

Fabiolita

was a barge that plied the Putumayo, hawking tinned meats and fluorescent

gaseosas

, or soft drinks, to the tiny villages dotted up and down the river between Puerto Leguizamo and Leticia. For a few pesos, we were invited to make ourselves comfortable on top of the cases of

gaseosas

that were stacked up in the center of the flat-bottomed barge and covered with a tarp. The crew furnished no spare tarps to protect us from the blazing Amazonian sun, but fortunately we’d brought our own and were able to set up a makeshift shade cloth.

We departed Puerto Leguizamo on a Saturday, February 6, 1971. One day before our departure, Apollo 14 had landed on the moon after its launch on January 31. This was only the third Apollo mission to reach the lunar surface; the previous mission, Apollo 13, had been aborted following an oxygen tank explosion in the service module on the outbound leg and barely made it back. Apollo 14 had relatively few problems and hence attracted less attention; a jaded public was already getting bored with the space program despite being perhaps humanity’s greatest adventure. Apollo 14 is mostly remembered for the two golf balls that Alan Shepard hit with a makeshift club he’d brought with him. It was also the mission on which astronaut Edgar Mitchell had his famous “savikalpa samadhi” experience, or mystic glimpse beyond the self into the true nature of things. Mitchell subsequently became interested in consciousness research, paranormal phenomena such as ESP, and went on to become a founder of the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS). To the distress of NASA, he also became a public advocate for UFO investigations, insisting the evidence for the extraterrestrial origin of UFOs was very strong despite efforts by a few covert figures inside the U.S. government to cover it up. I’d like to think Mitchell was tapping into some of the same strange vibes that had begun transmitting to us. He may have damaged his reputation, but I admire his honesty.

Whatever the public response, we were acutely aware of the mission through scattered news reports as we made our way into the Colombian Amazonas. We felt an affinity for the astronauts on their journey into the unknown. Drifting downriver, we, too, were impelled by the call of a mystery we felt to be no less worthy of pursuit. The weather was clear during most of our journey; occasional afternoon showers yielded to spectacular sunsets; and by the time the moon appeared in all its fullness the skies were crystal clear. One night, gazing up at the full moon, knowing our fellow humans were gazing down on us, we noticed something odd. There appeared to be a black mark, or a large shadow, on the moon, and nothing more; but what was it? We speculated that it might be the residue of a science experiment; perhaps the astronauts were dispersing carbon black over the lunar surface to measure albedo or some such thing. Our conjecture was absurd, though we did learn later that one of the mission’s objectives had been to crash the Saturn IVB booster into the moon and measure the resulting seismic activity. But that impact could not possibly have been observable from Earth, especially without a telescope. Whatever its source, the smudge was there, at least on one night. We all saw it. It was never mentioned, let alone explained, as far as we knew; I chalk it up to the ingression of one more peculiarity into the “real world” during our adventure. The farther we penetrated into the jungle, the more permeable became the boundary between ordinary reality and that of dreams.

Our destination after leaving Puerto Leguizamo was the mission of San Rafael at the mouth of the Río Cara Paraná. We were looking for “Dr. Alfredo Guzman,” as Terence called this figure in

True Hallucinations

. Guzman was a Colombian anthropologist working with the Witoto, together with his English wife and fellow anthropologist, “Annelise.” It was Guzman who had originally informed Schultes about the orally active

oo-koo-hé

preparation, so we figured he might give us some leads. From San Rafael, it was only a short trip via canoe to the village of El Encanto, the embarkation point for the trail to La Chorrera. The trail had been cleared in the early twentieth century to transport harvested rubber from La Chorrera to San Rafael for transport downriver on barges; tens of thousands had given their lives to build it. We had chosen the overland route because the alternative, to continue down the Putumayo to the next tributary, the Río Igara Paraná, and then take that to La Chorrera hundreds of kilometers upstream, would have added several weeks to our journey. Cutting across to the Igara Paraná, which roughly paralleled the Cara Paraná, would reduce our travel time to four days.

We didn’t encounter Guzman and his wife at San Rafael, but the padre assured us we would surely find them at El Encanto, where he’d recently moved to be closer to the Witotos. We lost no time in continuing on to El Encanto, a village whose name meant “the enchantment” or “the haunted,” evoking what felt like another synchronicity between the real world and our inner ideations.

There was no way to notify Guzman of our impending arrival, and he seemed unhappily surprised when we showed up. His wife, however, was more open to our company. Living among the Witotos meant her status had to be commensurate with the village’s other women. As custom dictated, she’d been living communally with them while Guzman dwelt in his own hut. The arrangement seemed quite exploitative to us, and hardly egalitarian, but who were we to judge? As for our colorful band, I can imagine Guzman’s dismay when we showed up in our white linens, long hair, beards, bells, and beads, accompanied by Solo’s menagerie of sickly dogs, cats, monkeys, and birds. We could have stepped into his scene directly off the streets of Haight Ashbury. Nevertheless, he pointed us toward an empty hut where we could hang our hammocks before moving on, which he obviously hoped would be sooner rather than later.

Sensing the tension, we told him what we had come for and assured him we’d be pressing on to La Chorrera as soon as possible. Guzman was not forthcoming when we enquired about

oo-koo-hé

. He seemed quite surprised that we even knew this word, and bluntly stated that to go to La Chorrera and start asking around about

oo-koo-hé

would be an inexcusable breach of protocol. It was a secret, he said, known only to the most powerful shamans and not supposed to be known to the rest of the tribe, let alone to a bunch of freaks from California. We did not press the matter.