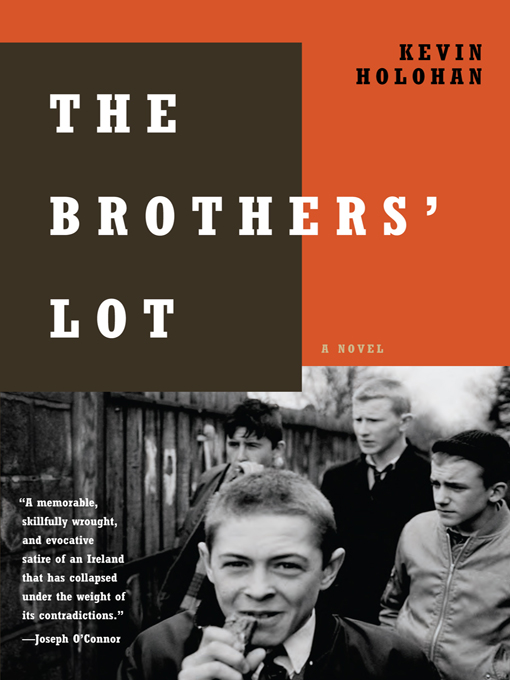

The Brothers' Lot

Authors: Kevin Holohan

This is a work of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

©2011 Kevin Holohan

eISBN-13: 978-1-617-75020-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-936070-91-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010939100

All rights reserved

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

For all the kids who never had a chance to answer back

Table of Contents

Whatsoever you do unto the least of these

my brethren, you do unto me.

—Matthew 25:40

W

ith a start Brother Boland woke. He had dozed off while praying at his cot. His coarse tweed undershirt was soaked in sweat. Around him pressed the deep silence of night.

He had been dreaming. He was flying through the air. He could see the school below him. He could hear a voice in the wind. It came from everywhere and nowhere and was filled with a strange harmony of anger, dust, and the smell of wood.

Brother Boland had started to circle lower over the school and suddenly, all lightness sucked from him, he began to fall toward the roof of the monastery. That was when he woke.

He got up off his knees and stared around the surrounding dark of his cell. Everything was as it had been for his last sixty years as a Brother. The statue of the Infant de Prague stood where it always had on the windowsill. His trousers hung on the chair as usual. His cassock hung on the back of the door as always like some outsized crow carcass. Everything was as it should be, yet not. Brother Boland could not put words on what it was, but there was something. He stepped into his slippers and threw on his cassock.

His slippers made a dead fish sound on the highly polished wooden floor as he tiptoed along. The half-light from the street slid through the windows and cast shadows everywhere. From his perch in the return of the stairs, Venerable Saorseach O’Rahilly, the founder of the Brotherhood, seemed to cower uncertainly back into the shadows, so unlike his stern, disciplinarian, daylight demeanor. Brother Boland nodded and blessed himself as he passed the statue and wisped down the stairs to the ground floor like a tattered black fog with the shakes.

In the monastery kitchen he checked all the doors and windows. Locked tight all of them. He ghosted through the ground-floor Biology lab. All secure there. He paused and leaned a moment against one of the big desks.

Satisfied that all was safe downstairs, Brother Boland twitched back up the stairs as fast as he could. At the top landing he wrestled with the stiff, heavy door. He opened it with a jolt. His hand spidered its way over the musty wood of the inner stairs until it found the light switch. He flicked it. Nothing. The darkness inside seemed to intensify in retaliation against his attempt to dispel it.

The air stank of damp and neglect. The narrow spiral stairs protested under Brother Boland’s feet as he cautiously ascended. The air was chill yet oppressive and Brother Boland labored to find enough oxygen to keep going.

The stairs led to another small landing. There Brother Boland paused and peered up into the gloom. He could just about make out the dull sheen of the bell above him. He paused, unsure whether to head up the ladder. He shivered. He brought his breathing to a minimum and listened. In the nearby flats a dog barked the bark of one who lives from dustbins. From closer came an answering howl hoping to reduce its desperate straits by sharing them. Such foolishness! He had not come all the way up here in the middle of the night to listen to dogs barking and speculate on how they found food!

He moved to the corner of the landing and reached down. His hands found the familiar boxy contours. This was his safe haven. This was where he came when the bad things closed in around him. This was his retreat.

Here he kept his tea chest. This was how he had arrived at the school: five months old, in the bottom of a tea chest with whatever clothes he owned thrown over him, left on the steps of the monastery by his unfortunate mother. There had been a note too, or so Brother Boland had been told, but that was long gone, as were the clothes. Yet he still had the tea chest, he still had his roots.

He sat on the edge of the chest and slowly rocked to and fro. He clutched each elbow and held himself close. As he felt his unease begin to subside, he reached out and ran his hands over the surface of the chest. He luxuriated in the familiarity of its shape and lovingly rubbed the rusted edging strips. His talonlike fingers felt love in the rough metal surface. He pressed at the tiny nail heads and sensed the love pulse into him. Brother Boland squeezed his eyes shut and ran his fingers faster over the metal edges of the box.

He emptied his mind. All he was aware of was the persistent tick-ticking of his middle finger on the side of the tea chest. He tried to listen behind that. There it was. There, just on the edge of the silence, was the sound of something different. Not new, but changed, differently evident. Boland shuddered. He felt a white light invade him but would not breathe for fear of putting the silence out of focus. He then felt a jolt as the silence slipped away from him. He tensed and twitched and with one final spasm he snapped into catatonic rigidity, unmoving as the walls around him.

When he woke the crows cawed harshly in the trees. The early trucks hauling toward the docks ground their gears like prophets’ teeth. Dogs barked their secret plans for the new day and softly the blinds and curtains of the early risers were drawn to admit the new dawn. In the early pubs, the dockers and the bona fides drank in uneasy alliance, all of them, either by choice or necessity, on a different timetable to the rest of the city. The tide shrugged out of the Liffey bringing in a cacophony of gulls to pick at the sludge in its shallows.

Brother Boland carefully placed his tea chest back in its corner and ran his hands lovingly over its surface. Whatever had haunted his night was gone. He glanced at his watch. He had two minutes to get to the bottom of the stairs and ring the bell for morning mass. He removed his slippers and tiptoed silently down the stairs.

F

inbar! Declan! Wake up, boys! It’s time to get cracking!”

His mother’s voice drifted in from the fuzzy outskirts of Finbar’s dream. It registered in his head for a few moments and then faded back into the muffled waking world.

“Finbar! Get up, will you, for the love of God!”

It was closer now. From out of nowhere light leapt at his eyelids. He scrunched his eyes shut and felt the covers being pulled off. He clutched at them but they slid from his grip.

“Now, Finbar! I won’t tell you again! Lord knows I have enough to be doing! Come on, love, please …”

His mother’s voice trailed off and he finally opened his eyes. She was standing there at the end of his bed, biting the knuckle of her index finger and staring at the wall.

“All right, mam, all right. I’m up!” he said brightly, and swung himself into a sitting position on the side of the bed.

Mrs. Sullivan nodded and smiled weakly: “That’s a good boy. I’ll just get Declan up then.”

In the bathroom Finbar ran the water. Stone cold. He splashed it on his face. Outside he could hear them at it already.

“Declan! Get up!”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

“Declan! I’m turning the light on now. Come on!”

“Yeah. Fine. Just leave me alone, will you?”

“Leave you alone, is it? Well, I’m sorry, Mr. High and Mighty, but you have to get up just like the rest of us. Finbar’s already up.”

“Well, isn’t he the little saint then?”

“Declan, that’s quite enough lip out of you. Just get up, can’t you?”

“I didn’t ask to go.”

“Not this again! Look, we’re going and that’s that. We’re not having this argument again. Now, get up out of that and stop your nonsense!”

“What if I don’t?”

“The movers will be here in half an hour.”

“Well, maybe I’ll get myself a flat then.”

“You will not! You don’t have two pennies to rub together. I’ll not have any more of this talk. We’ve heard enough of it out of you.”

Her voice was getting louder and shriller. Finbar sat on the toilet and ran the water in the sink as hard as it could go. He didn’t need to hear all this over again. There’d been weeks of it already and with each week Declan had become more disagreeable to the point where now he hardly spoke to anyone in the house, not even Finbar. All because that stupid Sheila Barry had dumped him or run away from home or whatever: no one was too clear on it.

“Yeah? And why not? I can do what I want!” yelled Declan.

“Not while you’re under my roof.”

“And who says I want to be under your roof? I didn’t ask to be part of this family. I didn’t ask to be born into this.”

“Oh, Sacred Heart of Jesus, Declan, stop it!”

Finbar heard the front door slam.

“What the hell is going on up there? Ye can be heard out on the street!” called his father from the bottom of the stairs.

“Nothing,” called Declan, the fire suddenly gone from his voice and replaced by a damp, leaden resignation.

“Well, fine then! Get up so! I got some sausages and bread from Mrs. Morrissey. Breakfast in ten minutes!” shouted Mr. Sullivan.

“Finbar, are you nearly finished in there? Declan has to wash himself,” called Mrs. Sullivan as she made her way back downstairs.

Finbar reached over and slowly turned off the water in the sink.

Once breakfast was over and the dishes washed, dried, and packed into the car, Finbar sat on the footpath outside the house and watched the movers load the furniture into the back of the truck. His father hovered around them, mostly getting in the way and making their job more difficult, but Jude Sullivan was not the type of man to trust hired workmen to do a good job unless he was breathing down their necks.