The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History (18 page)

Read The Bundy Murders: A Comprehensive History Online

Authors: Kevin M. Sullivan

On Labor Day weekend, Bundy, Liz and Tina joined Angie on her houseboat for a going-away breakfast, a celebration of sorts, as Bundy would be leaving the next day for Utah. Resting on the boat as it gently rocked back and forth in the water on what was a beautiful last day together must have been bittersweet for Liz. Living under the constant pressure of what she feared might be, and facing the reality that the man she loved would soon be far away was surely a drag on her emotions. When it was time for him to leave, Bundy "tickled" Tina, gave a "hug" to Angie, and then kissed the woman he loved." As he drove away, he looked back and waved, and life for Elizabeth Kendall would never be quite the same.

4

NIGHTMARE IN UTAH

Most references to Bundy's move to Utah give a timeframe of early September. Liz Kendall would later tell detectives that he left Seattle on September 3. However, gas receipts show Bundy began his journey to Salt Lake City on September 2, which was Labor Day that year. At first glance, the debate as to when Bundy left Washington appears to be only trivia, and totally insignificant. But Bundy, ever the lethal opportunist, would kill his next victim while traveling to his new home.

In her book, Liz recounts Bundy calling her when he reached Nampa, Idaho. The reason for the call, apparently, was twofold. After he said he loved her, they spent a few nostalgic minutes remembering when they had picnicked in Nampa during one of their excursions to see her folks back home. The words no doubt came forth from Bundy cloaked in sincerity and tied neatly together in love; at least, this is how Liz received them. But his mind was in a far different place now, and even while reminiscing with Liz, his eyes were scanning for a soul to possess. He would find what he was looking for shortly after saying goodbye.

Traveling on 84, Bundy was heading in an easterly direction through Idaho. The distance between Nampa, where he telephoned Liz (collect, no doubt), and Boise was just a hair over twenty-two miles, which would place him in the middle of Boise in just over thirty minutes. Prior to entering the city, however, on "the outskirts of Boise"' as Bundy remembered it, he spotted a young female with a green backpack hitchhiking at the top of the onramp of the freeway. Although he wasn't in the city proper, this portion of 84 ran through a neighborhood filled with "ranch style suburban houses ... in view,"' he said. It was early evening when Bundy pulled his beige VW Beetle, packed with his belongings for the move, into the emergency lane and motioned the young woman over to his car. With his good looks and winning smile, Bundy was everything a hitchhiker's driver should be. Without the slightest bit of trepidation, she returned the smile, opened the passenger door, and was soon chatting away with her handsome chauffeur on what would be the last ride of her life. Bundy would stop for gas the third time that day within the Boise city limits.

For the next three to four hours they kept on 1-84, which in those days was under construction, some stretches a modern highway and some an older and narrower road. This setup provided the perfect opportunity for what Ted Bundy had in mind, as it gave him easy access to the nearby river from one of the many turn-off roads connecting to the older highway. He had been eyeing the body of water as they talked, and it would be one of these cut-offs that Bundy would, under some pretense, travel down, while his unsuspecting passenger, perhaps for the first time, began to feel that initial twinge of fear. It was at this point he very carefully grabbed the crowbar from underneath the passenger's seat. Slowly raising it off the floor (but not so high as to be seen by her), he looked around, and seeing nothing but the blackness of night around them, he quickly brought the heavy iron instrument crashing into the right rear portion of her skull. This single blow did an incredible amount of damage to her cranium, knocking her unconscious. She was, however, still alive, just as Bundy desired. And while he wouldn't have the same kind of leisurely time with this victim as he had with the Hawkins girl and some of the others, he quickly stopped his vehicle, dragged the quivering body to a spot not far from his car, and stripped her of all her clothes. Highly aroused, he would have sex with her (perhaps anal), and would complete the act of murder through strangulation during the act of sodomy. Not wanting to leave so beautiful a sight, he may have stayed with her for a brief time, as he wanted to savor what he'd created. He could become especially excited viewing women in this fresh state of death,3 and before leaving her he would likely have had at least one, if not two, additional acts of copulation with the corpse.

Unlike previous occasions, however, he would not be taking her head for later pleasuring, nor could he return to her for additional acts of necrophilia, as he often preferred. And so, with a definite sense of regret, Bundy slid the body into the water, followed by all of her clothing, taking as much care as possible not to slip on the riverbank as he made his way back through the darkness with only a flashlight.

When questioned by investigators some fourteen years later, Bundy said after killing her he burned her identification and could no longer recall her name. He estimated she was between sixteen and eighteen years old, and said she had light brown hair, probably lived in Boise, and may have had Wyoming as her destination. The backpack, he said, did not go into the river like everything else, but was carried to Salt Lake City, where it was tossed out his car window in a spot where various dumps were located. It wasn't unusual, he said, to see discarded items scattered about the roadway in this area. The backpack, it seemed, would be quite at home in such a location.

Bundy's rooming house at 565 First Avenue, near the University of Utah. Bundy maintained an upstairs apartment, and may have carried some of his victims either up the stairs or by way of the fire escape to what one detective believed was his "lair."

It can be assumed that after killing the hitchhiker, Bundy proceeded on his way at the normal speed he was used to traveling. Nobody had been anywhere near him when he murdered the young woman, and it is also likely that no one paid any attention when he picked her up on the outskirts of Boise or when he refilled his tank in the city. So there was absolutely no need to hurry, except perhaps for the normal reasons, such as being exhausted from the day's drive. Nevertheless, he gassed up for the last time in Burley, Idaho, sometime after midnight, as his gas receipt bears the date of September 3, 1974. With approximately another 185 miles to go, his arrival time in Salt Lake couldn't have been earlier than 3:00 A.M., and was probably closer to 4:00 A.M. or later.

However early in the morning it was, he trudged up the steps to his second floor apartment at 565 First Avenue, and telephoned Liz, telling her how much he loved the place. The diabolic entity that had brought heartache, fear and terror to Washington State had quietly arrived in the heart of Utah in the wee hours of the morning, and while much of the city slept, the malig nancy was already setting up shop. Being able to kill with such ease whenever the urge prompted him was birthing a feeling close to omnipotence. As a hunter of young females, he was growing more self-assured with each passing day. His work (minus his slip of the tongue at Lake Sam) thus far had been flawless, and the madness which he unleashed at the first of the year would now be visited on the unsuspecting young women in this family-oriented and close-knit Mormon society. He would replicate here, he believed, what he had accomplished in Washington. Fresh from his latest kill, Bundy drifted off to a deep and satisfying sleep.

Five days after he left for Utah, the bodies of Denise Naslund and Janice Ott were discovered lying on a hillside just east of Issaquah, not more than ten miles southeast of Lake Sammamish State Park. Found with them was a third set of bones that would remain unidentified for many years. The discovery was made by a hunter walking up what was at one time a logging road, which connects to an older paved road angling off of 1-90. This connecting roadway is known to the locals as the old Sunset Highway. The entire area is ideal for disposing of bodies, as it offers seclusion at every turn. Not only is Interstate 90 flanked by woods on both sides, but the older highway is encased in trees as well. Anyone seeking privacy would have no trouble operating in this environment after dark, and had the remains not been placed so close to this road, they might have gone undiscovered for years, and possibly forever.

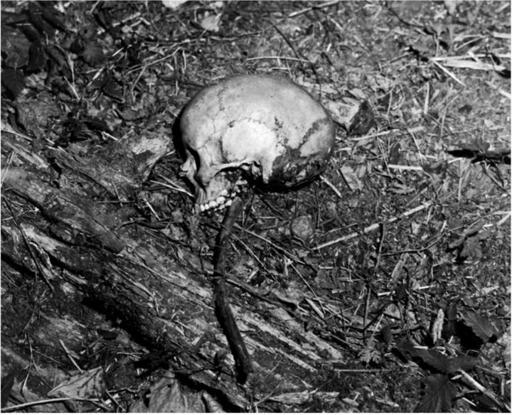

Elzie Hammons was a thirty-six-year-old construction worker by trade, and a grouse hunter by habit. He and a neighbor, seventy-one-year-old Elza E. Rankin, had returned to this spot after having bagged two birds in this same location during the previous year's hunt. "I was just walking through the brush on a grown-over road-years ago there had been an old logging road there," Hammons told a reporter for The Seattle Times. "The skeleton was right there on the ground."4 The skull, detached and hairless, lay nearby.

Hurrying back to where Rankin had parked his jeep, Hammons found him engaged in a conversation with a couple of teenagers who had come to the area to do some target shooting. When Hammons blurted out what he'd found, one of the boys, nineteen-year-old Jeffery Hartfield, let out a chuckle and assured him it was only an animal. Inviting them to come and see for themselves, Hammons began retracing his steps. Within moments they spotted something that Hammons had originally missed. "We found the clump of long black hair. It looked fresh and shiny ... about two feet long."' Suddenly, no one was laughing anymore. The hair belonged to Denise Naslund.

Skeletally speaking, there wasn't much left in its original form. As Bundy had anticipated, the creatures of the woods had fed on the dead, scattering the remains over a wide area. Authorities would use the painstaking help of volunteers to meticulously comb the rugged ground for every last bit of human bone and hair; a task both difficult and time-consuming. The brunt of the work would fall to an organization known as ESAR, or Explorer Search and Rescue. This dedicated group of some fifty teenagers led by adults would prove invaluable to Detective Robert Keppel, who watched them perform their meticulous, inch-by-inch search of the hillside for the next seven days. On hands and knees they worked by grids through the thick underbrush, keeping their eyes focused on the spot just before them as they concentrated on the task at hand. It was the kind of effort Keppel knew was beyond the desire of any cop to perform.' According to Keppel, the Issaquah crime scene would yield some four hundred pieces of evidence; a veritable "cache of human remains," he said. "We'd literally unearthed a graveyard, a killer's lair, where he'd taken and secreted the bodies of his victims."7

The skull of Denise Naslund, found by two hunters combing a hillside just east of Issaquah, less than ten miles from Lake Sammamish (courtesy King County Archives).

Although the skull and other remains of Denise Naslund would be located at the Issaquah site, the recovered remains of Janice Ott and the third victim would not include their skulls. Years later, Bundy would whisper to Keppel that the third victim was Georgann Hawkins and that her head had been buried on the hillside. However, with all the human debris collected by the ESAR contingent, it never occurred to Keppel that the killer may have, for whatever reasons, intentionally buried certain parts of his victims. Due to the physical changes which had evolved in the land during the fifteen years Bundy carefully guarded this secret, subsequent searches yielded nothing. The skull of Georgann Hawkins remains a part of the Issaquah crime scene to this very day.