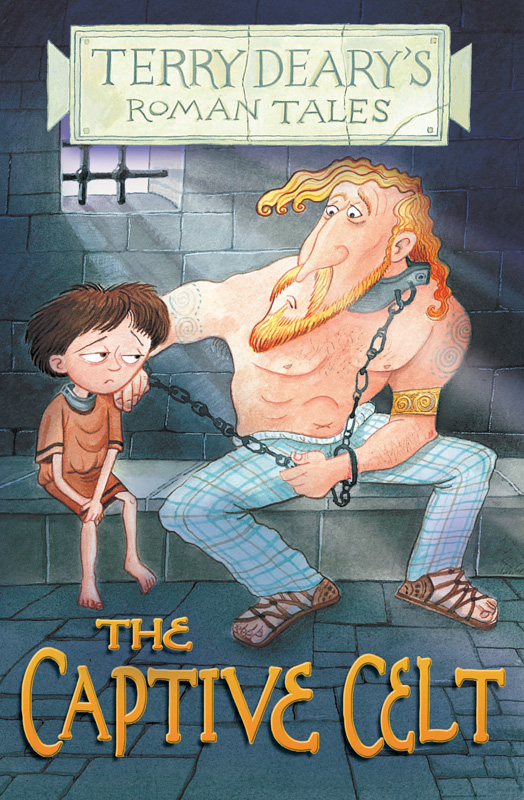

The Captive Celt

THE

CAPTIVE CELT

THE

CAPTIVE CELT

Illustrated by Helen Flook

A & C Black ⢠London

First published 2008 by

A & C Black Publishers Ltd

38 Soho Square, London, W1D 3HB

Text copyright © 2008 Terry Deary

Illustrations copyright © 2008 Helen Flook

The rights of Terry Deary and Helen Flook to be identified as the author and illustrator of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

eISBN 978-1-40813-879-3

A CIP catalogue for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means â graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems â without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

This book is produced using paper that is made from wood grown in managed, sustainable forests. It is natural, renewable and recyclable. The logging and manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Cox & Wyman Ltd.

Table of contents

Rome, AD 51

I am a slave. A pitiful, helpless boy, bullied by my master the senator's daughter, the cruel Livia.

I am a prisoner of Rome.

There is no winter in Rome ⦠not real winter like in Britannia, my home. And it was winter that defeated us, not just the Roman army. Winter and the shortest day of the year.

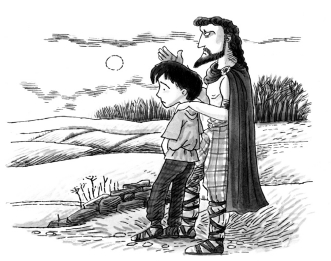

I remember what my father said. “The days are getting shorter â the sun is getting weaker. It happens every year. The grass will not grow and we will starve.”

“How can we make the sun stronger?” I asked.

“Give the gods a gift.”

“A gift?”

“A life.”

“A goat?” I had seen a goat sacrificed to the gods. The druids took their knives and cut its throat. They roasted the meat and ate it. I was given some of the scraps.

But this year, it would not be a goat.

“A man,” my father said.

“The Roman soldier? The one we captured?”

Father nodded.

The druids would never roast or eat a man. But they

would

kill him and give his life to our gods.

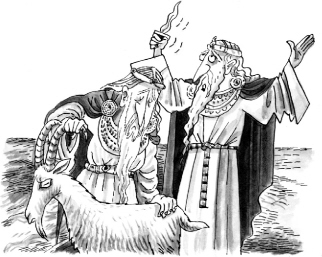

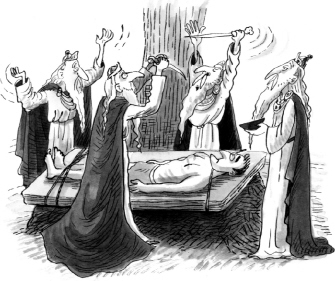

The whole village gathered on the path that led to the woods. The five druid priests in their white robes stood silent and still, though a wicked wind whipped at their hoods and blew through their beards.

The dark-skinned Roman soldier looked at us with scorn. He was not afraid to die.

The druids turned and walked slowly up the hill to the dark, bare trees. Our warriors led the way, guarding the prisoner. Children like me followed.

I tried to march like a warrior, but my little feet slipped in the muddy puddles. The only sound was the sighing of the wind in the trees and the crying of some of the babies the women carried.

“Why are you wearing your black war dress, Ma?” I asked.

“For luck,” she said. “This was the dress I was wearing when we attacked the Roman supply wagon.”

“Was that when we stole their corn?” I asked.

My mother nodded. “We ate well that night,” she said with a grim smile.

The druids stopped beneath a huge oak tree. The soldier was tied to a rough table raised on a bank of earth â the druid altar.

I watched wide-eyed and dry-mouthed for the knives to slice and the guts to spill. They said the druids could see the future from the way the guts fell to the ground.