The Carnival at Bray (13 page)

Read The Carnival at Bray Online

Authors: Jessie Ann Foley

But still.

Who dies at twenty-six? This isn't a cancer ward or a soldier in a strange country. This isn't a car going a hundred miles an hour on an icy road, a deer stepping out into the highway just as you turn the curve. A heart defectâwhat a sneaky and clinical way to die.

At first, Laura had suggested going home for the funeral by herself. “We don't have the money for four plane tickets,” she said. She looked so broken, slumped on Colm's couch sipping directly from a bottle of West Coast Cooler, that Maggie almost let it go without an argument. But her own grief was so consuming that trying to sympathize with Laura was like sleepwalking through someone else's dream.

“I'm going,” Maggie said, taking the empty bottle from her mother's shaking hands. “I loved him more than anybody.”

And maybe because Laura knew that was true, she relented. She put two flights on the credit card, and just like that, the very next evening, Maggie was sitting at her grandmother's house in front of the TV while Nanny Ei and Laura sat at the kitchen table, a box of tissue between them, picking out the readings for Kevin's funeral mass.

American television programming fell over her like an old blanket. She sat and flipped absently through the channels. There was

Cheers.

There was

Golden Girls.

There was local news about streets and neighborhoods she'd known all her life. Up and down she went, from CBS to NBC to ABC to WGN and back again. She thought of Eoin. Even in all the shock and heartbreak of the past twenty-four hours, her thoughts still returned, again and again, to that kiss. It now seemed so long ago. When would she see him again? Did he know that everything had changed for her? Was it okay to think about somethingâanythingâthat made her happy now that Uncle Kevin was dead? If he was up in heaven this very moment, and knew that in spite of her sorrow she still thought of kissing Eoin, would he feel betrayed?

“Nanny Ei?”

Her grandmother looked up from the mass booklet and took off her reading glasses.

“Yeah, honey?”

“Would it be okay if I went and sat in Kevin's room for a little bit?”

Nanny Ei looked at Laura.

“Do you think that's a good idea, Mags?” Laura asked.

“I won't touch anything.”

“I don't see the harm in it,” Nanny Ei said. “After all, you were one of the few people he actually allowed in that lair of his.”

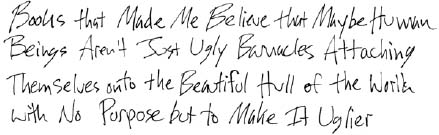

She could feel them watching her as she turned the knob on Kevin's door. The smell of his bedroom was thick with cigarettes and Old Spice deodorant. A small stick of incense sat on the windowsill with its long, white ash still intact. His bed was neatly made. Nanny Ei had smoothed the coverlet and tucked in the sheets after he had died in it and they had taken him away. His walls were covered with music posters: Nirvana, Soundgarden, Urge Overkill. Dinosaur Jr., Jimi Hendrix, Bob Dylan. The corners of the room were stacked high with books. Kevin had never been a good student and had barely graduated from high school, but he was a frequent visitor to the Mayfair branch of the Chicago Public Library, which was staffed by an old Belarusian who claimed to have been an English professor back in Minsk. They often went out drinking together, Kevin and Paviel, and the old librarian would give him book recommendations: the Russian greats, of course, but also the American writers who captured, as he put it, “the Spirit of Fuck You”: Ginsberg and the Beats, Whitman, Vonnegut, Richard Wright. Kevin had once made Maggie a handwritten list entitled “Summer Reading Recommendations to Keep Young Nieces Off the Streets.” It contained subcategories:

Maggie had tried to read one of these recommendations

âTropic of Cancer,

which was listed under the category

She had only been able to get through the first chapter. Now, on the nightstand next to his bed, she found a copy of

On the Road

with a pen stuck in the middle to mark where he'd left off. It was a book Kevin had talked about often, and it had appeared on her summer reading list under the simple category

Essential Reads

. Maggie sat on his bed and opened to the page where he'd stopped reading. A sentence was underlined in neat black ink:

I was surprised, as always, by how easy the act of leaving was, and how good it felt.

Maggie read the sentence a few times, wondering why he had marked it, whether he'd been thinking of Christmas morning at Colm's house, when he stood at the end of her bed and said good-bye to her. The words on the page blurred with her tears.

Before she left the room, Maggie went back and stood before his open closet, full of flannel shirts from the Salvation Army on Elston Avenue.

Those clothes are for homeless people,

Nanny Ei had scolded.

I can buy you nice new clothes at Kohl's. When you get your clothes at the Salvation Army, it's no different than stealing from the poor.

She leaned forward, put her face in the fabric, and breathed her uncle in. She felt him stronger than ever, then: waving to her from the wooden throne of his lifeguard tower, throwing his arm around her as they walked down Martello Terrace, leaning over the bar to talk to Eoin's aunt Rosie as if he'd known her all his life.

She thought of him standing next to her at the Metro, screaming along to the lyrics at the Smashing Pumpkins show:

tell me all of your secrets / cannot help but believe this is true

â¦

I cannot help but believe this is true.

She lifted one of the shirts from its hanger. It was gray and black plaid, the flannel pilled and threadbare: lived in. He'd often worn it, unbuttoned, over a ratty white T-shirt. She folded it and folded it again, stuffed it under her sweater, and snuck back into the front room. Her mom and Nanny Ei were still huddled over the funeral readings. Maggie knelt down next to the couch and opened her duffel bag. She lifted out the black dress she'd brought for the wake and placed the flannel at the bottom of the bag, gently, as if it still contained him, as if beneath the worn front pocket, she could still hear his heartbeat.

Before the wake, Maggie painted Nanny Ei's toenails. It was a ritual the two had shared since Maggie was in fifth grade and Uncle Kevin had forgotten to salt the icy back steps during a nasty cold spell. Nanny Ei had slipped a disc falling down the stairs and hadn't been able to bend down properly ever since. Laura had suggested she start getting pedicures, but Nanny Ei had dismissed nail salons as cesspools of foot fungus, and Maggie had been given the job. She didn't mind, though, because Nanny Ei didn't have old lady feet. They were delicate and softâsize fiveâpapered in thin white skin, and they smelled like the lemon bath salts she liked to soak her feet in while she watched reruns of

M*A*S*H.

“Honey, do me a favor,” Nanny Ei said as she stuck her foot out and Maggie began brushing a coat of fuchsia on her baby toe. “Stay away from those bum friends of Kevin's at the wake.”

“Okay, Nanny,” Maggie nodded, fixing a smudge with the edge of her thumb.

“I mean it, missy.” Nanny Ei pulled her foot away so Maggie had to stop what she was doing and look up. “The last thing I

need to worry about before I bury my son is Taco or Rockhead or any of those other degenerates chatting it up with my beautiful granddaughter.”

Maggie sighed and pulled Nanny Ei's foot back into her lap.

“Stop being crazy. Those guys are, like, ten years older than me.”

“Exactly! Perverts and degenerates, every last one of 'em. Except maybe that Sullivan boy.”

“Nanny! Kevin hasn't hung out with Sully since he quit Selfish Fetus to go to law school!”

“Is that right?” Nanny squinted at her newly pink big toenail. “Well, if that bastard thought he was too good for Kevin, he still better show his face at the wake. You

always

go to the wake, Maggie. Even when you don't want to.

Especially

when you don't want to.”

She began to cry then, suddenly, and Maggie finished painting her toenails in silence.

The parking lot of Cooney's funeral home was freshly plowed, and mountains of dirty snow were pushed up as high as the chain-link fence. Nanny Ei turned off the ignition and they sat for a moment, listening to the car tick. Finally, Laura took a deep breath and looked at Maggie in the rearview mirror. Her eyes were puffy, but her hair was tied back into a neat bun and she wore a new shade of dark red lipstick.

“Are we ready, you guys?” She reached back and squeezed Maggie's hand. Maggie squeezed it back.

“Mom?”

“Yeah, babe?”

“You look really pretty.”

Laura's eyes filled immediately with tears. Maggie realized, with a stabbing sense of guilt, how cruel she'd been to her mother since the move to Ireland. She reached into her coat pocket and

closed her fist around Kevin's broken compass. If anything good had come of his dying, it was that they had all chosen, at least for now, to forgive each other.

They were the first ones to arrive, followed shortly by Maggie's uncle Dave, his wife, and their three boring children. As the oldest child in the family, Uncle Dave was everything that Kevin wasn'tâMaggie had never seen him wear anything other than khakis and a golf poloâand for this reason, she had never trusted him. He had escaped into the Navy, married a wide-hipped woman named Marjorie, and now worked as a mortgage broker in Oklahoma City. He had three daughtersâCaelynn, Taylor, and Kimberly, who were all around Maggie's age. They all wore headbands and cardigans and spoke with voices bleached of any regional accent. They only came to town once a year, and when they saw Nanny Ei, they hugged her with cold affection and called her “Grandma.” Maggie was glad her cousins were there, though, because it was easier to concentrate on how much she hated them than to face the wave of agony that lapped at her heart when she saw the open coffin at the front of the room.

At first, she could not go look at him. Nanny Ei and Laura went up to the coffin together. They crouched on the velvet kneeler, held hands, and cried. They prayed. They whispered to him. Nanny Ei reached out and stroked his hair and put a rosary in his interlaced fingers.

When they were finished, Uncle Dave and Marjorie approached the coffin, and Maggie stared at the clean bottoms of Marjorie's ugly shoes. Then the daughters went up, all three together. They squeezed together on the kneeler, leaning over to stare at Kevin's face. Taylor, the youngest, whispered something and Caelynn and Kimberly snorted with sudden laughter. They crossed themselves hastily and scurried back toward their seats, while Maggie cracked her knuckles and glared at them, daring them to smile or laugh just one more time.

Before the doors opened for the public viewing, Nanny Ei came over and sat next to Maggie on one of the vinyl chairs near the back of the room.

“If you want to go up and say good-bye to him, I can come with you,” she said.

Maggie nodded and let Nanny Ei take her hand and lead her up to the coffin. She felt like a very small childâfrightened, weepy, everything in the world both new and strange.