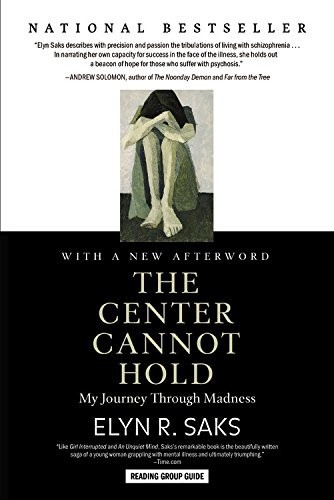

The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness

Read The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness Online

Authors: Elyn R. Saks

Tags: #Teaching Methods & Materials, #Biography, #General, #Psychopathology, #Health & Fitness, #Personal Memoirs, #Women, #Diseases, #Psychology, #Biography & Autobiography, #Schizophrenics, #Education, #California, #Social Scientists & Psychologists, #Mental Illness, #College teachers, #Schizophrenia, #Educators

THE CENTER CANNOT HOLD

ELYN R. SAKS

Contents

ITS TEN O'CLOCK on a Friday night. I am sitting...

WHEN I WAS a little girl, I woke up almost...

DURING THE SUMMER between my sophomore and

junior years in...

IN SPITE OF the fact that Nashville's Vanderbilt

University was...

AFTER GRADUATING FROM Vanderbilt University in

June of 1977, I...

SET AMONG THE green and gently rolling hills of

Oxfordshire...

ALL THROUGHOUT THOSE first long hours of my

second stay

I STUMBLED INTO Elizabeth Jones's office in a

desperate lunge...

FOUR YEARS AFTER coming to Oxford, I finally

completed my...

AS ALWAYS, MY family greeted me at the airport in...

I FULLY EXPECTED THAT someone from Student

Health would...

ONCE WE'D ARRIVED at YPI, the EMTs took me by...

FOR A PLACE that existed ostensibly to promote the

mental...

THE FIRST PATIENT I met once back at YPI was...

I RETURNED TO New Haven a few weeks before

classes...

DURING SECOND SEMESTER, we were free to choose

whatever classes...

AS THE END of law school drew near, I knew...

TAKING THE TEACHING job, even though it was not

at...

IN SEPTEMBER, I went back to my second year of...

I WAS BEGINNING to feel somewhat comfortable with

a few...

KAPLAN WAS ASKING me to surrender. That's the

way I...

THINGS WITH KAPLAN were not going well. No

matter what...

ONCE, BACK IN New Haven, White had told me that...

I WAS NEARLY forty years old, and for the very...

THE HUMAN BRAIN comprises about 2 percent of a

person's...

prologue

I

t's TEN O'CLOCK on a Friday night. I am sitting with my two

classmates in the Yale Law School Library. They aren't too happy

about being here; it's the weekend, after all—there are plenty of other

fun things they could be doing. But I am determined that we hold our

small-group meeting. We have a memo assignment; we have to do it,

have to finish it, have to produce it, have to...Wait a minute. No,

wait.

"Memos are visitations," I announce. "They make certain points. The

point is on your head. Have you ever killed anyone?"

My study partners look at me as if they—or I—have been splashed

with ice water. "This is a joke, right?" asks one. "What are you talking

about, Elyn?" asks the other.

"Oh, the usual. Heaven, and hell. Who's what, what's who. Hey!"

I say, leaping out of my chair. "Let's go out on the roof!"

I practically sprint to the nearest large window, climb through it,

and step out onto the roof, followed a few moments later by my

reluctant partners in crime. "This is the real me!" I announce, my arms

waving above my head. "Come to the Florida lemon tree! Come to the

Florida sunshine bush! Where they make lemons. Where there are

demons. Hey, what's the matter with you guys?"

"You're frightening me," one blurts out. A few uncertain moments

later, "I'm going back inside," says the other. They look scared. Have

they seen a ghost or something? And hey, wait a minute—they're

scrambling back through the window.

"Why are you going back in?" I ask. But they're already inside, and

I'm alone. A few minutes later, somewhat reluctantly, I climb back

through the window, too.

Once we're all seated around the table again, I carefully stack my

textbooks into a small tower, then rearrange my note pages. Then I

rearrange them again. I can see the problem, but I can't see its

solution. This is very worrisome. "I don't know if you're having the

same experience of words jumping around the pages as I am," I say. "I

think someone's infiltrated my copies of the cases. We've got to case

the joint. I don't believe in joints. But they do hold your body

together." I glance up from my papers to see my two colleagues staring

at me. "I...I have to go," says one. "Me, too," says the other. They seem

nervous as they hurriedly pack up their stuff and leave, with a vague

promise about catching up with me later and working on the memo

then.

I hide in the stacks until well after midnight, sitting on the floor

muttering to myself. It grows quiet. The lights are being turned off.

Frightened of being locked in, I finally scurry out, ducking through the

shadowy library so as not to be seen by any security people. It's dark

outside. I don't like the way it feels to walk back to my dorm. And once

there, I can't sleep anyway. My head is too full of noise. Too full of

lemons, and law memos, and mass murders that I will be responsible

for. I have to work. I cannot work. I cannot think.

The next day, I am in a panic, and hurry to Professor M., pleading

for an extension. "The memo materials have been infiltrated," I tell

him. "They're jumping around. I used to be good at the broad jump,

because I'm tall. I fall. People put things in and then say it's my fault. I

used to be God, but I got demoted." I begin to sing my little Florida

juice jingle, twirling around his office, my arms thrust out like bird

wings.

Professor M. looks up at me. I can't decipher what that look on his

face means. Is he scared of me, too? Can he be trusted? "I'm

concerned about you, Elyn," he says. Is he really? "I have a little work

to do here, then perhaps you could come and have dinner with me and

my family. Could you do that?"

"Of course!" I say. "I'll just be out here on the roof until you're

ready to go!" He watches as I once again clamber out onto a roof. It

seems the right place to be. I find several feet of loose telephone wire

out there and fashion myself a lovely belt. Then I discover a nice long

nail, six inches or so, and slide it into my pocket. You never know

when you might need protection.

Of course, dinner at Professor M.'s does not go well. The details

are too tedious; suffice it to say that three hours later, I am in the

emergency room of the Yale-New Haven Hospital, surrendering my

wire belt to a very nice attendant, who claims to admire it. But no, I

will not give up my special nail. I put my hand in my pocket, closing

my fingers around the nail. "People are trying to kill me," I explain to

him. "They've killed me many times today already. Be careful, it might

spread to you." He just nods.

When The Doctor comes in, he brings backup—another attendant,

this one not so nice, with no interest in cajoling me or allowing me to

keep my nail. And once he's pried it from my fingers, I'm done for.

Seconds later, The Doctor and his whole team of ER goons swoop

down, grab me, lift me high out of the chair, and slam me down on a

nearby bed with such force I see stars. Then they bind both my legs

and both my arms to the metal bed with thick leather straps.

A sound comes out of me that I've never heard before—half-groan,

half-scream, marginally human, and all terror. Then the sound comes

out of me again, forced from somewhere deep inside my belly and

scraping my throat raw. Moments later, I'm choking and gagging on

some kind of bitter liquid that I try to lock my teeth against but

cannot. They make me swallow it. They make me.

I've sweated through my share of nightmares, and this is not the

first hospital I've been in. But this is the worst ever. Strapped down,

unable to move, and doped up, I can feel myself slipping away. I am

finally powerless. Oh, look there, on the other side of the door, looking

at me through the window—who is that? Is that person real? I am like

a bug, impaled on a pin, wriggling helplessly while someone

contemplates tearing my head off.

Someone watching me.

Something

watching me. It's been waiting

for this moment for so many years, taunting me, sending me previews

of what will happen. Always before, I've been able to fight back, to

push it until it recedes—not totally, but mostly, until it resembles

nothing more than a malicious little speck off to the corner of my eye,

camped near the edge of my peripheral vision.

But now, with my arms and legs pinioned to a metal bed, my

consciousness collapsing into a puddle, and no one paying attention to

the alarms I've been trying to raise, there is finally nothing further to

be done.

Nothing I can do. There will be raging fires, and hundreds,

maybe thousands of people lying dead in the streets. And it will

all—all of it—be my fault.

chapter one

When I

WAS

a little girl, I woke up almost every morning to a

sunny day, a wide clear sky, and the blue green waves of the Atlantic

Ocean nearby. This was Miami in the fifties and the early

sixties—before Disney World, before the restored Deco fabulousness

of South Beach, back when the Cuban "invasion" was still a few

hundred frightened people in makeshift boats, not a seismic cultural

shift. Mostly, Miami was where chilled New Yorkers fled in the winter,

where my East Coast parents had come (separately) after World War

II,

and where they met on my mother's first day of college at the

University of Florida in Gainesville.

Every family has its myths, the talisman stories that weave us one

to the other, husband to wife, parents to child, siblings to one another.

Ethnicities, favorite foods, the scrapbooks or the wooden trunk in the

attic, or that time that Grandmother said that thing, or when Uncle

Fred went off to war and came back with...For us, my brothers and me,

the first story we were told was that my parents fell in love at first

sight.

My dad was tall and smart and worked to keep a trim physique. My

mother was tall, too, and also smart and pretty, with dark curly hair

and an outgoing personality. Soon after they met, my father went off

to law school, where he excelled. Their subsequent marriage produced

three children: me, my brother Warren a year-and-a-half later, then

Kevin three-and-a-half years after that.

We lived in suburban North Miami, in a low-slung house with a

fence around it and a yard with a kumquat tree, a mango tree, and red

hibiscus. And a whole series of dogs. The first one kept burying our

shoes; the second one harassed the neighbors. Finally, with the third,

a fat little dachshund named Rudy, we had a keeper; he was still with

my parents when I went off to college.

When my brothers and I were growing up, my parents had a

weekend policy: Saturday belonged to them (for time spent together,

or a night out with their friends, dancing and dining at a local

nightclub); Sundays belonged to the kids. We'd often start that day all

piled up in their big bed together, snuggling and tickling and laughing.

Later in the day, perhaps we'd go to Greynolds Park or the Everglades,

or the Miami Zoo, or roller skating. We went to the beach a lot, too;

my dad loved sports and taught us all how to play the activity du jour.

When I was twelve, we moved to a bigger house, this one with a

swimming pool, and we all played together there, too. Sometimes

we'd take the power boat out and water-ski, then have lunch on a

small island not far from shore.

We mostly watched television in a bunch as well—

The Flintstones,

The Jetsons, Leave It to Beaver, Rawhide,

all the other cowboy shows.

Ed Sullivan and Disney on Sunday nights. When the

Perry Mason

reruns began, I saw them every day after school, amazed that Perry

not only defended people but also managed to solve all the crimes. We

watched

Saturday Night Live

together, gathered in the living room,

eating Oreos and potato chips until my parents blew the health whistle

and switched us to fruit and yogurt and salads.