The Chisholms (15 page)

“I’ve never been to Baltimore,” she said. “What sort of place is it?”

“Oh, it’s very nice,” Sarah said.

Silence.

They were sitting together inside the Comyns wagon, sunlight illuminating the cover so that everything within took on a golden glow. The wagon was packed even more tightly than the Chisholms’ own. They sat on stools the carpenter himself had made, swaying with the roll of the wagon, bouncing whenever it hit a ridge or a rut. The baby was asleep on Sarah’s lap. This morning she’d suckled the child in the privacy of her own wagon; Minerva guessed the carpenter had spoken to her about showing her teats to all and any.

“Big city, is it?” Minerva said.

“Oh, yes,” Sarah said.

“About the size of Louisville?”

“I guess,” Sarah said.

Silence.

“Did you live in the city itself?” Minerva asked. “Or outside of it?”

“Yes.”

“In it?”

“Yes.”

Silence.

“Husband have a shop there?”

“Yes,” Sarah said.

“Must be interestin being married to a man can fashion things with his own two hands.”

“Yes, it is,” Sarah said.

“Hadley puts his hand to making a table or chair, it comes out all catty-wampus.”

“Oh, yes,” Sarah said, and laughed.

“My Gideon’s the one has a sure hand with a hammer and nail,” Minerva said. “You haven’t met him; he’s off with his brother in Illinois. Man stole my eldest son’s horse, big raindrop gelding, beauty of a horse. Just rode off with it one night. I miss him somethin fierce,” she said, and found herself confiding to Sarah that Gideon was her favorite, had been from the minute the granny woman laid him puny and wet across her belly. Loved them

all

to death, she did, but for Gideon she felt something special, a kind of...

joy,

she supposed it was, every time she saw him. She knew it was wrong worrying about them the way she did; they were both grown men and knew how to take care of themselves. But they’d been gone more’n three weeks already. Last time she’d seen them was on the twentieth of May, Gideon waving from his saddle, big grin on his face.

all

to death, she did, but for Gideon she felt something special, a kind of...

joy,

she supposed it was, every time she saw him. She knew it was wrong worrying about them the way she did; they were both grown men and knew how to take care of themselves. But they’d been gone more’n three weeks already. Last time she’d seen them was on the twentieth of May, Gideon waving from his saddle, big grin on his face.

“I guess that’s the nature of it, though,” Minerva said. “Worrying over your children even when they’re all growed up.”

“Oh, yes,” Sarah said.

Minerva decided she was a twit.

When they stopped for their nooning that day, it seemed a break in the routine, though it was itself a part of it. The sky had been blown flawlessly clear by the storm the night before; they could see everywhere around them for miles and miles. A stream surprised the landscape here. They watered the animals and drank themselves, and then filled the barrels and kegs. Bobbo and the Comyns boys started the cooking fires, and the women fried the meat and boiled the vegetables they’d bought in Independence. There was the smell of coffee and of warmed corn bread. After the noonday meal, they dozed. The voices of Annabel and Willoughby’s eldest girl broke the golden stillness.

“Do you get it now?”

“No, I don’t.”

She had stringy brown hair and eyes like a cat’s, yellow with flecks of green. Must’ve been her mother’s eyes; Willoughby’s were as brown as Christmas pudding. Her name was Julia.

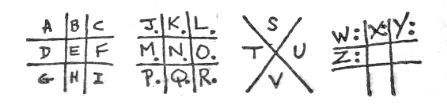

“It’s a cipher, is all,” Annabel said.

“But what use is it?”

“Say I want to send you a letter in Lancaster—”

“I don’t live in Lancaster no more.”

“Just say. And I wanted to tell you something secret.”

“What would you want to tell me?”

“Well... I don’t know,” Annabel said. “Say I wanted to cuss or somethin.”

“Would

you?”

you?”

“Course not, we’re just sayin. So I’d whip out the cipher here and write it all in code, and nobody but you or me’d be able to read it.”

“Let me see it again,” Julia said.

Annabel showed her the scrap of paper.

“Say you wanted to make an A,” Annabel said.

“Yeah, how’d you do it?”

“You see those lines around the A there?”

“What lines?”

“The one under it, and the one comin down to meet it. You just draw them two lines

instead

of the A,” Annabel said. “Them two lines take the

place

of the A — you get it?”

instead

of the A,” Annabel said. “Them two lines take the

place

of the A — you get it?”

Julia studied the cipher again. “But then it’d be the same for J, wouldn’t it?”

“No, the J’s got a dot.”

“Oh,” Julia said. “Yeah.”

“You get it now?”

“Yeah,” Julia said, nodding.

“It’s good, ain’t it?”

“It’s

real

good,” Julia said. “Where’d you learn it?”

real

good,” Julia said. “Where’d you learn it?”

“Everybody back home knows it,” Annabel said.

What had appeared dull in southern Illinois seemed exciting now in retrospect. There, at least, a ridge, a knoll, a hillock rose occasionally to startle the unexpecting eye. Here, there was a wide road trodden level, the land on either side of it as flat as the road itself, stretching toward a horizon visible wherever one turned.

The effect was stultifying.

The wagons moved at the center of a perfect circle, the circle unchanging, the landscape eternally the same, the mules and the oxen and the horses plodding ahead but succeeding only in moving the circle intact, center and circumference, so that there was a sense of standing still rather than progressing.

They came fourteen miles that second day. The day before, they’d come sixteen by the chart. They were bone-weary when they formed the circle again at sunset. They made their fires, they posted their guards. They ate. They slept. In the morning, they moved on again.

They were emigrants, they supposed.

You look forward to nooning, Bobbo thought.

Damnedest thing ever.

Get off your horse, stretch your bones, eat some good hot food. Sit around afterward doing nothing. Just looking all around. Dozing. Looking again. Over there in the back of the Oates cart was Timothy’s Indian wife. Never budged out of that cart. Sat there day and night, you’d think her backside was glued to it. Appeared every bit as sorrowful as the widower, staring out over the prairie. Always looked west. Bobbo followed her gaze one time. Thought maybe she was seeing something he couldn’t make out. Wasn’t nothing out there. Not a damn thing.

Timothy’d brought her some food, and now he was taking his sketch pad and a boxful of pencils from the cart. Way he talked about painting and drawing made it sound like it was

work.

Like plowing a field or shoeing a horse. Bobbo couldn’t understand that. Friend of his, Roger Colby back home, was always drawing pictures, too, some of them pretty enough to frame. Bobbo himself couldn’t draw a straight line, but he admired people who could do that sort of thing. Draw pictures, a dogwood tree or something. But work? Hell, it wasn’t

work.

Still hadn’t seen any of Timothy’s pictures, didn’t know whether the man could really draw or was just wasting his own good time and God’s, too. He was sitting on a big rock now, watching every move the carpenter made. Trying to get a likeness, Bobbo supposed.

work.

Like plowing a field or shoeing a horse. Bobbo couldn’t understand that. Friend of his, Roger Colby back home, was always drawing pictures, too, some of them pretty enough to frame. Bobbo himself couldn’t draw a straight line, but he admired people who could do that sort of thing. Draw pictures, a dogwood tree or something. But work? Hell, it wasn’t

work.

Still hadn’t seen any of Timothy’s pictures, didn’t know whether the man could really draw or was just wasting his own good time and God’s, too. He was sitting on a big rock now, watching every move the carpenter made. Trying to get a likeness, Bobbo supposed.

There was the widower Willoughby, sorrowful as could be. Never knew when he wa9 going to break into tears. Last night just before supper, Annabel said something about the nice stitching on the pinafore his toddler was wearing. Willoughby put his face in his hands and started crying. Must’ve been his wife had made the pinafore. Went back to his wagon, climbed up on the seat, sat there with his face in his hands, weeping. Wouldn’t touch a bite of food. His daughter Julia went over to him and touched him on the shoulder.

“Pa?” she said.

“Yes, darlin.”

“Pa?”

“Yes, darlin, that’s all right, darlin.”

Timothy was still trying to draw a picture of the carpenter. Be a miracle if he got anything at all down on paper, way Comyns ran around like a man half his age. Maybe

had

to move fast to keep that titty young wife of his happy on her back. Bobbo got up from where he was sitting, and wandered over to Timothy. His head bent over his pad, he kept scribbling away with the pencil. Bobbo stood directly in front of him, trying to sneak a look around the edge of the pad. Didn’t want the man to think he was nosy.

had

to move fast to keep that titty young wife of his happy on her back. Bobbo got up from where he was sitting, and wandered over to Timothy. His head bent over his pad, he kept scribbling away with the pencil. Bobbo stood directly in front of him, trying to sneak a look around the edge of the pad. Didn’t want the man to think he was nosy.

“How many miles you expect we’ll cover today?” he asked.

“Oh, fourteen, fifteen,” Timothy said, without looking up.

“Has Willoughby talked to you about maybe turning back?”

“He has.”

“Do you think he will?”

“I’m hoping not,” Timothy said.

“Seems a man

talking

about it so much is a man going to do it. Don’t it appear that way to you?”

talking

about it so much is a man going to do it. Don’t it appear that way to you?”

“Maybe,” Timothy said. “What do you think of this?” he asked suddenly, and turned the pad so Bobbo could see it.

Jonah Comyns was there on paper exactly.

Quick sure pencil strokes delineated the long angular body with its massive chest and shoulders, the oversize hands and thick fingers. A thatch of hair sprouted from the head of the drawn image as wildly and as randomly as did Comyns’s real hair. Here, too, were the quirky eyebrows and fiercely burning eyes, the nose that could split a log, the thickish lips, and something more — Timothy had captured on paper the restless energy of the man. Looking at the pencil sketch, Bobbo was certain it would leap off the page at any moment, run scurrying to tend to the animals or the fire, shout an order to a son.

He did not know he could be so moved by pencil marks on paper. Speechlessly, he stared at the drawing, and realized that Timothy was waiting for his reaction.

“It’s the most beautiful thing I ever seen,” Bobbo said.

There was an instant’s silence. Timothy looked up sharply into Bobbo’s face, searching it for insincerity. Then, so softly Bobbo almost couldn’t hear him, he said, “Thank you.”

Sarah Comyns was nursing her baby when the Indian appeared.

They’d camped the night of the thirteenth on the bluffs overlooking the Kansas River, three to four miles wide there, the river valley thick with timber, the hills rising from a prairieland as green as Minerva’s eyes. In the morning, they moved on to a nooning place where the river was boiling yellow. Their rest period seemed in contrast more peaceful than it normally did, the stillness of the camp exaggerated by the incessant roar of the river. The men were talking about how they planned to get to the other side. Timothy suggested that they take off the wheels and float the wagons across like barges. But there were no hides to nail to the bottoms, and Comyns was afraid they’d sink without waterproofing. Hadley thought they should build themselves a raft. There was plenty timber to cut, and fashioning a raft was a simple thing enough. The women had washed the dinnerware and put it up already; Minerva and the girls were resting now in the shade under the trees. Inside the Comyns wagon, Sarah briskly removed a breast from within the unbuttoned yoke of her bodice, reacquainted her baby’s mouth with the oozing nipple, and then cupped breast in hand, kneading it, her eyes closed as the baby began to suck. When lazily she opened her eyes again, the Indian was staring in at her from the rear of the wagon.

He was at least five feet ten inches tall, his face an oval with prominent cheekbones, eyes almost the color of his skin, long black hair falling to his shoulders. He said something to her, Sarah didn’t know what and didn’t care. She yanked her squirting breasts loose from her baby’s mouth and began screaming. The Indian turned and ran from the wagon. He got no more than ten feet toward the woods beyond when Jonah Comyns dragged him kicking to the ground. There was a pistol in Comyns’s hand. He put it at once to the Indian’s head. In that moment, Timothy came running around the corner of the wagon. “Hold your fire!” he yelled, and clamped both hands onto the carpenter’s wrist.

“Let go!” Comyns shouted. “I’ll shoot the bastard dead!”

Inside the wagon, the baby began shrieking. The Indian was babbling frantically now, the pistol flailing closer and closer to his head, Timothy desperately trying to hear his words over the baby’s squawling and Comyns’s shouting. The widower Willoughby came running toward the wagon with his suspenders hanging, a rifle in his hands, his face pale. The youngest Comyns boy ran up and began dancing a frightened little jig.

“Let him be!” Timothy shouted. “He wants to ferry us across the river!”

From inside the wagon, Sarah said, “He spied me naked.”

The Indian was a Delaware.

He had come as spokesman for his tribe, searching for someone with whom he might negotiate, and had peered into the nearest wagon only to find himself face to face with a crazed white woman. Now that everyone had calmed down, he explained that his tribe, together with their partners the Shawnee, had constructed a raft sturdy enough to transport the party across the river. This for a price the white man would surely recognize as reasonable. He said all this in Algonquian — which Timothy understood but incompletely. He gathered the Delaware’s name was Ferocious Storm, but it might well have been Fearful Storm, or indeed Fear of Storms; the Indian spoke quite rapidly, never once deferring to Timothy, who was trying to converse in a tongue not his own.

Other books

Jilted by Ann Barker

Ultimate Desire by Jodi Olson

The Darkfall Switch by David Lindsley

Black Pearl by Peter Tonkin

We Are Here by Cat Thao Nguyen

Travel Bug by David Kempf

Try a Little Tenderness by Joan Jonker

Hit and Run by Cath Staincliffe

Seduced by the Enemy (Blaze, 41) by Jamie Denton

Feathers by Peters, K.D.