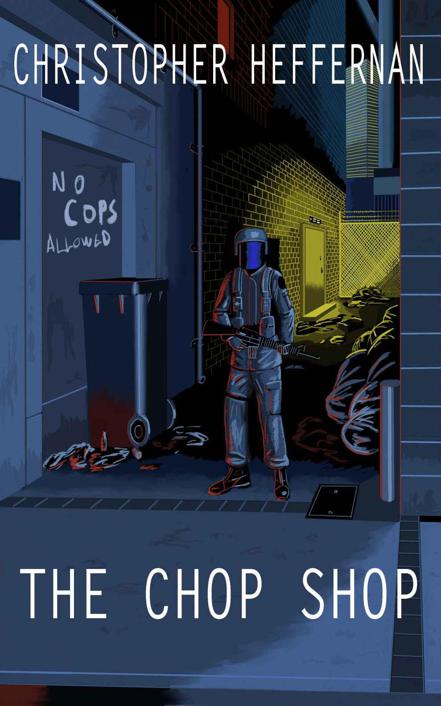

The Chop Shop

Authors: Christopher Heffernan

The Chop Shop

By Christopher

Heffernan

Text copyright ©

Christopher Heffernan

All Rights Reserved

Michael tensed

up, leaning over the side of the bath to grab the pistol on the floor. He

checked the safety and climbed out. A patch of mould growth spread over the

plastic blinds, which he tweaked open and peered down onto the street below.

A platform of

dark concrete blocked his view of the sky, lit by the flashes of searchlights

as they swept back and forth across the ruins of Lower London. Hazardous waste

dripped past the window from a leaking sewage pipe hundreds of meters above.

His car still sat in its parking space, newly adorned with the remains of

broken bottles and surrounded by chain fence and barbed wire.

Michael removed

the plank of wood propped up against the door handle. He walked into the

lounge, still clutching the gun in his clammy hands and switched off the alarm

clock. His heart rate quickened as he removed the second plank from the front

door. A draft crept under the door and turned his toes cold.

Memories of the

previous night resurfaced in his consciousness. Michael raised the gun, gritted

his teeth and opened the front door. The hallway was empty, complete with the

scent of the same decomposing body from one of the empty flats. Fresh gang tags

marked the wall opposite him, sprayed on with pink paint.

He sighed to

himself and shut the door. It was seven-twenty in the morning, and it was going

to be a very bad day. He moved to the shadows to dress in his suit, and then

used the hand-pump to force water through the purifier and into the waiting

glass. He popped three tablets from their blister packs, each one shaped

differently, and dropped them into the water. He shook the glass gently and

watched as they dissolved into a white haze.

Michael drank it

down to the last drop. He had decided it tasted like rat poison left to melt on

the tongue, only instead of killing him, it kept him alive.

He slipped on

his belt holster and let the .45 lodge within the depths of the leather. Three

pockets carried spare magazines. It was seven-forty when he finally stepped out

of the flat with a plastic carrier bag of foil wrapped sandwiches, still cold

from the night they'd spent in the fridge.

A searchlight

swept past the shattered window at the end of the hall, and he felt a gust of

chill wind blow against his face and ruffle his tie. The stench of death was

stronger in the air now, so strong that he gagged. One converted warehouse,

forty flats, thirty-eight of them deserted, and one home to the corpse of an

old man. He wondered which ailment had killed him, and then decided that he

didn't really want to know.

Now he was the

only living thing for nearly two hundred meters in every direction. He lingered

in the hall for a moment, wondering if there was anything worth salvaging from

the flat. Probably not.

He walked

through puddles of water formed by leaking pipes, reflecting the crimson glow

of LEDs, and took the stairs down. The sight of ruined cars greeted him. They

had turned to rust, those parts which had not be scorched black by fire,

untouched for a decade since the war ended.

Bleached

skeletons sat slumped in the remains of their seats, as tattered newspapers

drifted down the road, riding on the wind. Michael went around to the back

where his car sat in its security pen.

He fumbled with

the orange and brown padlock and opened the gate. Broken glass bottles crunched

beneath his shoes as he slid into the driver's seat of the navy blue car. A

mangy fox strolled past the fence, pausing to look up at him before it

continued on with its head bowed low.

Michael keyed

the ignition. The radio came on after the engine, playing him the last five

seconds of an old song he'd heard a dozen times before. It changed to the news.

A female reporter launched into a monologue about the Basingstoke Butcher and a

rise in cases of uncontrolled cannibalism amongst the surviving population.

Then she started

on a story about an airliner crashing under mysterious circumstances. He

sighed, turned the radio off and drove onto the road.

His hands were

clammy with sweat as he remembered the war and those memories of Berlin; long

nights of burning ruins and smoke that blocked out radioactive green skies,

moving through sewers that shook under the weight of tanks above ground, and

all those people convulsing and vomiting as they died from nerve gas.

He remembered

lying still under corpses, pretending to be dead, with only a gas mask between

him and the nerve agents. Russian gunships loitered in the air, hunting for

survivors with their thermal sights. He'd feel the vibrations of approaching

tanks in the rubble, waiting for the helicopters to move on, and then he'd see

the soldiers approaching, dressed from head to toe in CRBN equipment. They'd

move slow, marching alongside the tanks, sometimes stopping to kick over debris

and corpses as they checked for survivors.

He'd wait, trembling

from fear, and they'd always come closer. He'd reach for the detonator, flick

the switch and watch as they vanished in a flash of fire and smoke. Then he'd

have to run, and it was the part he always hated the most, praying he'd get

back to the manhole cover before the survivors found him.

It was late

enough in the morning now for people to walk the streets in small groups.

People with jobs, sometimes drug dealers or car clamping gangs. Sometimes he

saw other cars or a bus. An aerial drone flew past at low altitude.

Croydon pillar

emerged from the darkness, towering over nearby buildings; a mass of concrete,

steel and advanced composite materials, with navigation lights that flashed

from top to bottom.

Michael turned

the corner. Croydon police station occupied the compound to the south, where a

security checkpoint stopped him a hundred meters away. Concrete blocks walled

off the approach, guarded by a machine gun nest and an infantry fighting

vehicle.

A policeman

stepped forward as Michael lowered the door window. He raised the visor on his

helmet, face hidden by balaclava and dressed in a black combat uniform sporting

the Assurer corporate logo on its sleeve.

“Morning,

Detective. You know the drill.”

Michael reached

inside his coat's interior pocket and fished for the identity card. He listened

to another policeman complaining about security for a construction team. His

accomplice laughed with a cocaine snort and suggested that they should have

shot them all and dumped the bodies in the ditch. Law enforcement through

superior firepower.

He couldn't find

his card. The policeman leaned closer, and his eye twitched, out of focus for a

moment before it returned to normal. He blinked it away. One of the others was

selling drugs to a trio of addicts inside a doorway.

“Give me a

minute. It's here somewhere,” Michael said.

The policeman

sniffed to clear his nose and shifted his rifle to the other hand. “It's okay,

take your time. I've been here all night; I'm not going anywhere soon.”

Michael checked

his other pockets. He found the card in his trouser pocket. The policeman took

the card, held it up so the hologram caught the light, and then swiped it

through the card reader he held. A red light flashed. The reader gave a buzzing

sound.

“Shit,” the

policeman muttered. He turned to the others. “John, it's broken again. Come and

fix it.”

Michael sighed

and slumped in his seat. He could see some of Croydon station's array of

armoured vehicles just beyond the checkpoint. A trio of policemen patrolled the

parking area. Somebody was screaming, and one by one the policemen turned to

look. People burst through the station's main entrance. A woman fell, and the

people behind trampled her to death.

Croydon station

exploded in a flash of flame. The fire consumed it, lashing out at those

fleeing before it was snuffed out by an advancing wave of black smoke that sent

the checkpoint guards stumbling to the ground. Bits of metal, concrete, bone,

and flesh rained down on them.

A severed arm

landed on his windscreen. It still moved back and forth, given life by the

rumble of the car engine. The dust cloud swallowed him alive.

Michael stopped

his car at the checkpoint. The policeman tapped his knuckles on the window

until he lowered it. “ID.”

Half a dozen

others watched him. Two sat behind sandbag emplacements, gripping the handles

of machine guns. Michael handed over his identity card. The policeman ran it

through his scanner, and the light flashed green.

He glanced up at

Michael. “The replacement? We've been expecting you, Mr Ward. Go on through.

Park in section A. The desk officer will get you to where you need to be.”

One of the

others slid back the chain fencing and raised the barrier. The sign once said,

“Richmond Station,” but had since been changed with thick, red paint, so that

it now read, “The Chop Shop.”

The paint had

trickled before it had dried, and it seemed as though the sign had been

bleeding. He drove forward, finding the surrounding houses boarded up with wood

and metal. One had collapsed inwards on itself, now a mess of whitewashed

brick, broken glass and shattered roof tiles, taking part of the adjoining

buildings with it.

The winds sucked

pieces of rubbish across the street like tumble weed, and distant tower blocks

loomed over urban decay. Past the checkpoint was the old high street, formerly

a bastion of economic prosperity with four takeaways, a café and a launderette.

Tables and

chairs were still set out. The umbrella shades had rotted, leaving rusted metal

spokes exposed to the open air like spider legs, and beneath them skeletons

slumped in their seats, still garbed in the remains of their clothes. Their

bone smiles suggested they were still laughing from a joke shared a decade ago.

One of the

takeaways was called

The Chop Shop

, and Richmond station piggy-backed onto

it like an architectural tumour of metal and glass, induced by a toxic case of

lax planning laws. The rest of the area had been bulldozed, concreted over, and

walled off to make room for police facilities.

He parked his

car where the policeman had told him to. A perimeter wall topped with razor

wire and patrolled by lone policemen separated the compound from the rest of

the world. Concrete bunkers shaped like angular aircraft hangers housed the

armouries. One policeman stood beside a doorway, oblivious to the no smoking

sign bolted to the wall as he puffed away on a cigarette.

Two more stood

guard by the main entrance, cradling rifles as their postures sagged with the

weight of boredom. Michael left his car and entered the building, setting off

weapon scanners as he passed through. One of the policemen leaned around the

corner to stare at him. A finger inched over the trigger guard of his rifle.

He handed his

identity card and .45 over to the policeman hidden behind a screen of armoured

glass in the security booth and passed through again. Silent. The policeman

slid them back over the counter, nodding towards the reception area.

“Go on through.”

Plastic trees

decorated the corners of the reception area. A television screen hung from the

wall, displaying footage of the nine o'clock news. The chairs were losing their

covers to wear, and clumps of yellowed foam spilled out of the gaps like human

fat.

A man stood in

the middle of it all, a little over six feet tall, holding a roll-up between

two fingers as he exhaled smoke through the nose. He had grey hair and a

moustache, dressed in black police fatigues, with the trousers bloused at the

boots.

Michael

exchanged a stare with him. The man's lips curled upwards at the corners. He

stubbed the cigarette out in a glass ashtray that hadn't been emptied for

months and approached. Up close, Michael could see a weariness in the man's

expression. They shook hands.

“I'm pretty sure

I know who you are,” the man said in a Scottish accent. He glanced at his

watch. “You're also one minute and thirty-five seconds late, but seeing as it's

your first day here, I'll cut you some slack. Come with me. We'll get you

briefed and set up.”

The man swiped

his security card through the reader and led Michael through a corridor once

pristine white, but now yellowing and beginning to turn brown. “I'm Major

Harris, commander of Richmond station, but we like to call it the Chop Shop.”

“I saw the sign

out front, sir.”

They stopped at

a pair of lifts. Harris slapped the button. “These things take a while.

Everything breaks here sooner or later.”

Two policemen

stood guard a little further on, backs turned.

“I don't

understand it, Corporal. The corpses never fit the body bags. It's like trying

to lift a sack that keeps sagging.”

The corporal nodded

knowingly. “It's what I like to call the bacon effect. You go to your local

supermarket, and sometimes on those rare and precious occasions, they have a

supply of bacon. Long and streaky bacon rashers, and you think to yourself,

'yum, that bacon sure looks tasty. There's enough of it to fulfil my dietary

requirements for today, and I really want to buy it,' right?"

“I suppose so.”

“You remember

the last food riot and decide that starving for four days on the trot is

unpleasant, so you buy it at the rigged price, get home and put it in your

frying pan. The smell makes you salivate; your stomach rumbles. Disaster

strikes. Suddenly those huge rashers of bacon that looked so tasty start to

shrink and shrivel up. Now they look tiny, and you feel like you've been ripped

off. You're angry. Do you know why that happens? It's because the supermarkets

pump it full of water.”

“I never really

gave it much thought.”

The corporal

shrugged. “Well, Private, the exact same principle applies to people. Like

bacon rashers, we are mostly made of water, and when we are incinerated by fire

the moisture is removed from our bodies. We shrink and shrivel up until we look

like an anorexic on a sun bed. Body bags are made for stabbings and shootings,

not cases where Jimmy accidentally blows up the entire estate because he smells

gas and forgets to turn the pilot light off. So you see, it's the bacon

effect.”