The chuckling fingers

“Other people may think they’d like to live their lives over, but not me—not if this last week is going to be in it. Out of what has just happened at the Fingers both Jacqueline and I got something worth keeping, but Heaven defend me from ever again having to stand helplessly by while it becomes more and more apparent to almost everyone but me that the person I love most in the world is murderously insane… .

“I never again want to know the panic of being up against evil coming out of a mind so much more skillful than mine that even the signs we did see—the acid in a bride’s toilet kit, the burned matchsticks under a bed, the word scrawled with a child’s blue chalk on a rock—all just bogged us deeper in terror and despair….”

Copyright © 1941 by Mabel Seeley

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

This One

For Janice

To the eternal glory of Minnesota there is such a place as the North Shore. Otherwise this story is entirely fictitious; there is no such estate as Fiddler’s Fingers, and the people I put there, the events 1 have happen there, are entirely imaginary.

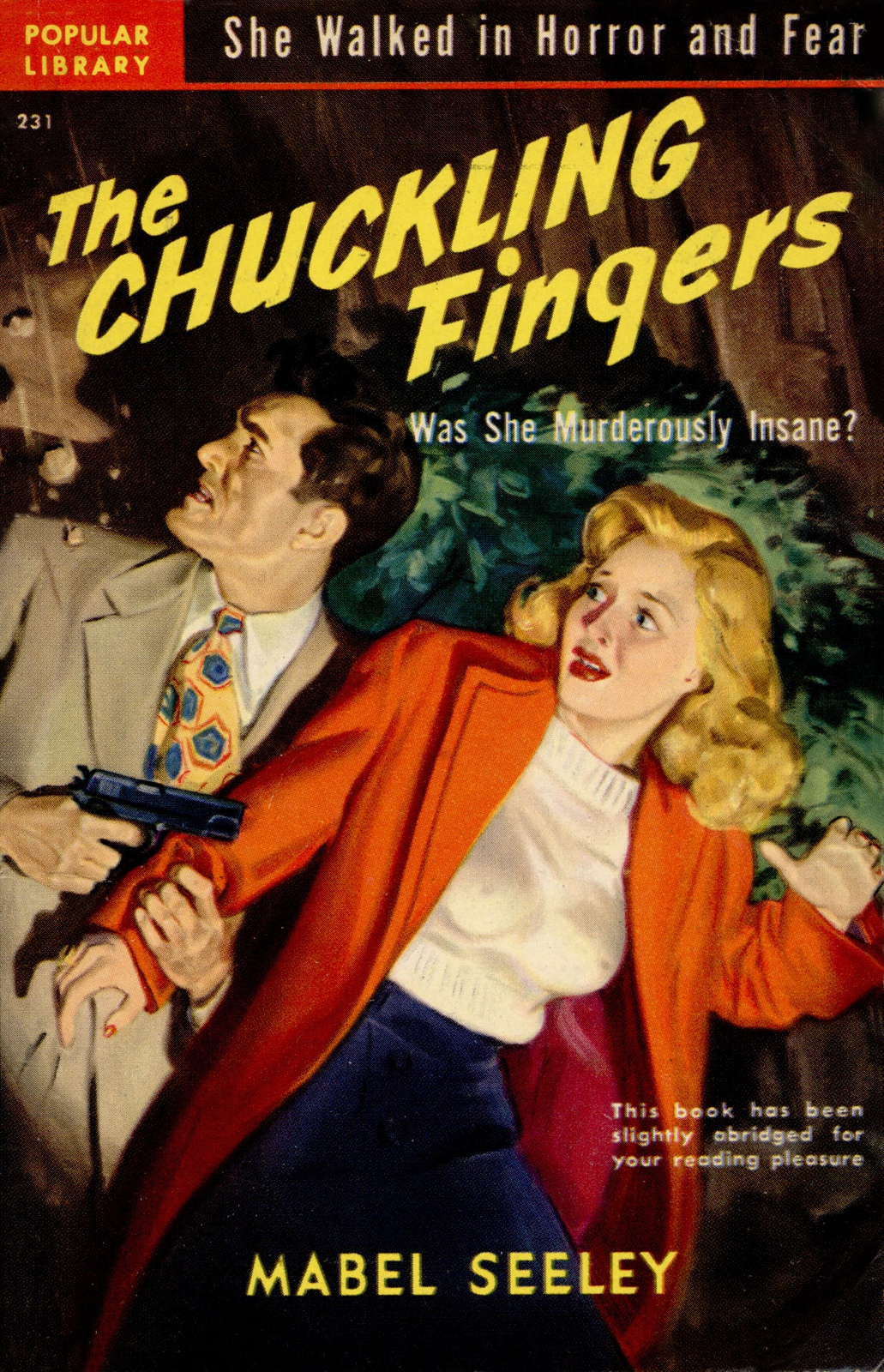

- Cover

- Dramatis Personae

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- About Mabel Seeley

- Bibliography

Fiddler’s Fingers, a remote and pine-grown private estate on the North Shore of Lake Superior.

Ann Gay

, stenographer in an insurance office, twenty-six. If trouble was a lake she’d dive into it head first.

Jacqueline Heaton

, Ann’s lovely cousin, whose second marriage precipitates crime.

Toby Sallishaw

, not-yet-three, Jacqueline’s daughter by her first marriage to Pat Sallishaw.

Bill Heaton

, lumberman, Jacqueline’s new husband, whose Heaton inheritance includes the Heaton luck.

Fred Heaton,

Bill’s brash nineteen-year-old son by his first marriage.

Myra Heaton Sallishaw

, Bill Heaton’s cousin, and mother of Jacqueline’s first husband, Pat Sallishaw.

Phillips Heaton,

who believes the world owes a Heaton a very good living. Myra’s brother.

Octavia Heaton

, so often unseen and unheard, younger sister of Myra and Phillips.

Jean Nobbelin

, Bill’s business partner, French Canadian.

Mark Ellif

, just out of college, engineer of one of the Heaton-Nobbelin pulpwood freighters.

Bradley Auden

, old friend of the Heatons, and owner of an estate east of Fiddler’s Fingers.

Carol Auden,

Bradley’s impulsive eighteen-year-old daughter. Her hair is red.

Cecile Granat,

man’s girl, but also something else.

Ed Corvo,

owner of the resort west of Fiddler’s Fingers.

Ella Corvo

, Ed’s wife.

Lottie Elvesaetter,

Ella’s sister, occasional maid at the Fingers.

Dr Rush,

physician and coroner, who has work on his hands.

Paavo Aakonen

, tenacious sheriff of Cook County.

OTHER PEOPLE may think they’d like to live their lives over, but not me—not if this last week is going to be in it. Out of what has just happened at the Fingers both Jacqueline and I got something worth keeping, but heaven defend me from ever again having to stand helplessly by while it becomes more and more apparent to almost everyone but me that the person I love most in the world is murderously insane. Heaven forbid that I ever again see a car moving like Frankenstein, of its own power and volition, carrying a secret burden into a lake, or that I ever again grasp an arm and feel that rigid marble chill or that I ever again have to look on while a blood-drenched shirt is ripped away from the terrible red hole a bullet makes in living flesh.

I never again want to know the panic of being up against evil coming out of a mind so much more skillful than mine that even the signs we did see—the acid in a bride’s toilet kit, the burned matchsticks under a bed, the word scrawled with a child’s blue chalk on rock—all just bogged us deeper in error and despair. I never again want to have a flying figure come hurtling at me from an unlit staircase or wake in the morning to find my bathrobe slashed or stand endless hours facing a door, fighting a vicarious fight. Any time in my life is going to be too soon for me to want to feel again that I’m a member of a looming last-man’s club, with death walking hooded in the night, relentless and remorseless and successful.

Someone, I suppose—some Heaton—will live on at Fiddler’s Fingers. But it’ll be all right with me to be away from that particular slash of water, that particular brush of wind, that near inhuman chuckle that came to sound like laughter at all law and right and civilization.

* * *

The funny thing is that even on the day I rushed up to the North Shore from Minneapolis I was expecting trouble. Not the kind of trouble I got—just nice, ordinary trouble I could smooth over in a wind. Smoothing over my beloved cousin Jacqueline’s troubles isn’t entirely new in my life; we’d lived together since she was four and I seven. This second marriage of hers to Bill Heaton was bound, I thought, to take adjustments, considering that she had a daughter of two and he had a son at the university. Undercurrents of restraint had run through Jacqueline’s recent letters, and then there ‘d been that out-of-the-blue note from Jean Nobbelin which had catapulted me in to ask my boss for a week’s vacation. Two days after I got Jean’s note—eleven-fifteen on the morning of the Fourth of July, to be exact—I was clinging to the guardrail of the North Shore bus as it slowed for its Grand Marais stop. My neck cricked so I could peer through a window, my feet ready to get me through the door the moment it opened. One glance at Jacqueline, I thought, would tell me what was wrong and how much.

That girl on the bus seems awfully simple and unsuspecting to me now.

Just before the bus jolted still I had an instant’s glimpse— against a backdrop of sun-dazzled white cement, filling station and blue lake—of what looked like a completely normal family group: Jacqueline in the fuzzy blue sweater and white slacks I’d given her for her Bermuda honeymoon, Bill all white flannels and almost terra-cotta skin and, down below, holding Jacqueline’s hand, the pink, small, bouncing mite that was Toby.

Then the bus door folded open, and there was nothing between us but a pushing fat woman with suitcases. In an instant I had Jacqueline’s shoulders in my hands.

That was when dismay slid all the way down my interior like a liquid silver fish.

Over Jacqueline, like a fever, was what looked like shivering expectation—no, worse than that, fright. Her eyes were full of it, eyes so lovely you couldn’t usually see anything except their loveliness, brown flecked against a green as dark as pine needles.

She laughed; she hugged me; she cried lightly, “Ann! We’re so delighted! Your wire surprised us so!”

She didn’t mean it.

I said stupidly, “What’s wrong?” Through all the insecurity of our childhood we’d been almost one person; even that brief and tragic first marriage of hers to Pat Sallishaw hadn’t separated us. But she was shut off from me now; she moved out of my hands, her eyes avoiding me.

“Wrong?” she repeated as if the word had no meaning. “But nothing’s wrong, darling. Here’s Bill and Toby… .”

Her head with its free-blowing dark hair was thrown stiffly back. I stood caught in so much bewilderment that for an instant I didn’t see or hear anything—foretaste of a state that was to become all too familiar.

Then there was a grab at my knees, and I had to tune in Toby, her hands pulling at my skirt, her small pink face impatient and demanding.

“Me! Me! I here!”

I bent to scoop her up.

Usually Toby can grab my attention and keep it—Toby, who’s not yet three and who has funny, wispy, colorless hair sticking out in all directions like tangled petals on an aster,

Toby, whose eyes are like Jacqueline’s, and who has the promise of Jacqueline’s exquisite, full, bursting mouth. Toby, who’s almost all that’s left now of those five months when Jacqueline was Pat Sallishaw’s wife.

The small arms gave me one immense return squeeze before the independent back inside the pink corduroy coveralls stiffened.

“I get down now,” Toby decided, and slid.

A long brown hand slid in over her head as I looked up to the grin on Bill Heaton’s warmly hued, imperious face.

“My turn.” He shook my hand hard, the grin intensifying. “Ever thought about going in for pole vaults, Ann? You stepped clean over one fat woman and three suitcases, getting out of that bus. I’ll bet I could get you in the next Olympics.”

I babbled something.

Sunlight was blazing back from the white concrete of the filling-station driveway on which he stood; some of that light seemed to come from his easy, commanding strength. I suppose every woman thinks there must be a man like Bill Heaton somewhere if she could only find him. But when I looked closely at the face that was all smooth, brown-red planes meeting at the bold ridges of his brow and nose and chin I saw what was hidden under his jocularity. The corners of his wide, generous mouth were tight, and his eyes—darker and warmer brown than his skin—had been looking at shock.

Suddenly instead of seeing them as they were now I saw them turning from the flower-banked altar in the living room of Myra’s Duluth house on the tenth of May to face the people who had come to see them married. They’d stood caught up in a kind of shining, supreme content.

Eight short weeks to make this change.

* * *

As we drove eastward the twelve miles from Grand Marais to Fiddler’s Fingers they made an effort to seem normal and casual, but I just felt more and more strongly that something strange was wrong. We sat all of us abreast in the one capacious seat of Bill’s low old topless car, Bill driving, Toby’s head bobbing at my elbow, Jacqueline at my right, staring almost silently straight ahead. With an impatient movement of his wide shoulders against the gray kid of the seat back. Bill began talking about the thousands of acres of cutover woodland he owned near Little Marais and near Hovland, about the crews he kept continually cutting the softwood as it reached the right size and the other crews who replanted. He bought wood from other pulp farmers, too, and what he could get from the government out of Superior National Forest; it was all dumped in Grand Marais Harbor to be loaded on his freighters, to go to Fort William and Duluth and Detroit, to become paper, matchsticks, laths, fence pickets.

I’d known he was a lumberman; I didn’t listen very hard. All my antennae hunted for the sources of disturbance. The countryside through which we passed drew little of my attention until after fifteen minutes of riding the car swung to the left, through the open wrought-iron gate of a tall spiked iron fence.

Jacqueline roused to speak almost the only words she’d said since we left Grand Marais.