The City Son

Authors: Samrat Upadhyay

Copyright © 2014 by Samrat Upadhyay

All rights reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. References to real people, events, establishments, organizations, or locales are intended only to provide a sense of authenticity, and are used ficticiously. All other characters, and all incidents and dialogue, are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Upadhyay, Samrat.

The city son / Samrat Upadhyay.

p. cm

ISBN 978-1-61695-381-2

eISBN 978-1-61695-382-9

1. Young women—Nepal—Fiction. 2. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PR9570.N43U63 2014 823′.92—dc23 2013045388

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

v3.1

For Babita and Shahzadi

Contents

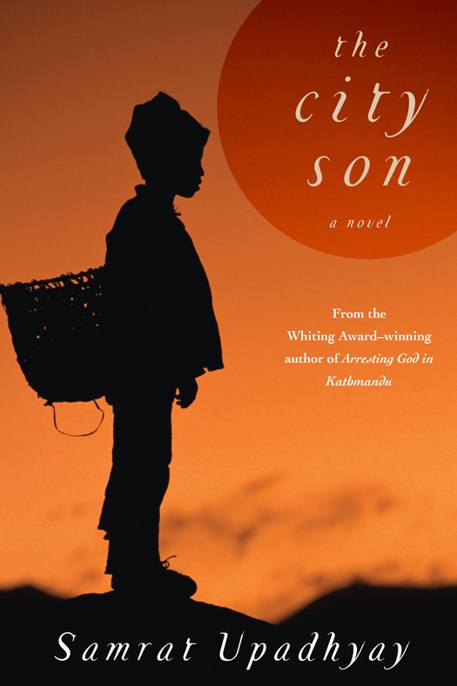

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

PART 1

CHAPTER ONE

A

STRANGER COMES

to the village and delivers the news.

Didi hears a woman’s voice in her yard. She’s upstairs, going through the boys’ old clothes, deciding which ones she wants to keep and which ones to pass down to a neighbor’s children. Her first thought when she hears the woman’s voice is that something has happened to her husband in the city. Then she knows it’s something else. She stands still, holding in her hands a pair of dark blue shorts, too tight for her older son, Amit. “Is anybody home?” the woman cries out again. Didi goes to the window.

“Are you the woman named Sulochana?”

Didi nods.

“I have to talk about an important matter.”

The woman identifies herself as belonging to the next village, then she makes some connections—throws out some names—that form a vague picture in Didi’s mind about who she is. A sickly feeling has started in Didi’s stomach. She doesn’t want to hear this woman. I should shut this window, she thinks, and I can go back to sorting my boys’ clothes. But there is no going back.

“Sometimes I feel like my heart is going to break,” the Masterji wrote in a letter not too long ago, “at the thought of not being able to come home again this year. My heart is going to shatter into pieces—that’s what I feel. But this separation is not for long, Sulochana. Next year I am sure to visit.” Didi had squinted at the words, mumbling them to herself for coherence; she had studied only up to seventh grade. At home he never called her by her name, but in all his letters he addressed her as “Sulochana.” In the evening when the boys had come home, she’d told them, “Next year. He can’t come this year—too many students. That’s what you get for having a brilliant father.” She’d formed her own picture of the name her husband had amassed in the city: people greeted him when he strolled the streets. Each dawn when the air was fresh and vibrant, he made rounds of the temples. His forehead smeared with

tika

, he returned to his neighborhood, drank tea in his favorite shop before going to the school where he taught in the morning session. He returned home around noon and soon thereafter received

his first students, to whom he gave his private tutoring. Sons and daughters of high-ranking officials lined up at his door to seek his assistance.

“The other day, the prime minister’s wife came to see if I could tutor her nephew,” he’d written. “I told her that she ought to have sent someone to fetch me, but she said that she didn’t want to disturb me when I was hammering away and chiseling the shape of young minds. Hadn’t the king himself often said that the youth of today are the nation builders of tomorrow? She observed the four students I was tutoring at the moment, all of whom were staring at her slack jawed, and said that four nation builders were already in the making. Sulochana! The prime minister’s wife! What did I do to deserve this luck? Sometimes I feel that I don’t even deserve you and the boys. How patient you have been with me in this absence, this

peeda

of our long separation.”

Peeda

: she loved the word he used for his torture.

Peeda

was what she felt, too, except she never expressed it.

The sickly feeling carries a smell that rises from her stomach to her mouth. It’s like the odor of an animal. The shorts she holds in her hands have a urine spot that has not completely washed away. What’s going to happen to my boys? she reflects. But it’s too late, and she knows it. She’s not at the start of this momentum; she’s already in the middle of it. The boys are going to suffer. Other people, unknown faces she hasn’t yet met, are going to suffer—people who are now suddenly connected to her.

“Are you going to invite me in?” the woman asks.

“Whatever you need to say, feel free to say from the yard.”

“The matter is a bit too delicate for the open air.”

“It’s okay.”

“

Kasto kura nabujheko bhanya

. It’s for your sake I’m urging privacy.”

“I perfectly understand. Either tell me right here or go your own way.”

The woman looks annoyed, but then she begins to speak. Her manner of speaking is singsongy, as if she were reciting a favorite ditty from her childhood.

The woman finishes speaking her main bit, pauses, then continues, “I wouldn’t have gone through the trouble of coming here and talking to you had I not been told that you have been kept in the dark about this for years now. How is that possible? I asked myself. How is it that a wife would not know about this big a secret her husband has kept in the city? What kind of wife would not know this? Then I had to see for myself what kind of wife. Now that I have seen you, I know you don’t deserve it. What woman does? You have given your life to your husband, haven’t you, Sulochanaji? And look at the news that I have brought you.

“I’ve seen the boy walk hand in hand with his mother in the market. The boy has immaculately smooth skin and perfectly dimpled cheeks and large, curious eyes. His mother is also exceptionally beautiful. Like an actress in a film, that kind of beauty. A city kind of beauty,

sahariya

type, the type one finds in magazines. Her face is longish and perfectly shaped. She is petite, loves to wear red. Apsara is her name. Yes, a nymph—that’s what her parents named her. She was a student of his. She came to his flat for tutoring so she could pass the SLC and college exams. Then one day she didn’t return home. Her parents disowned her; her brother came to thrash your husband. But she told everyone her place was with him in that sparse flat in the crumbling house in the busy intersection of the city’s core.

“When I saw her she was dressed in a shimmering red sari as though she had been wedded that very day. The whole street was glowing because of her. People stopped to look at her, then at her son. You know where this was? Right in the Asan market. Soon you’ll know what kind of place Asan is. It’s very close to Bangemudha, where your husband lives, near the large wooden lump studded with coins. People say nailing coins into that wood has a palliative function, but I can’t remember what it cures. Stomachache? Toothache? This is the type of neighborhood where small bands of men with flowers in their hair and cymbals and drums pass through—amazing how only three or four men with their instruments make the sky throb. Not too long after the boy was born, your husband decided that the one-room flat wasn’t big enough, and now they’ve moved to a small house with a separate kitchen and an indoor bathroom. It’s not a bad place. The rent is more expensive than the previous flat, but then your husband is also getting more students to tutor now.

“In the Asan market that day, the boy’s mother was smiling at everyone. The boy was sucking on an ice cream. His beauty made my heart ache, Sulochanaji. I was told that the boy’s mother never wore anything other than bright red—bright red sari, bright red blouse with dhoti—as though it were the festival of Teej all year long. When she was pregnant with the boy, she put a big red

tika

on her forehead, I was told, and with her rouge and her red

sindur

smeared on the parting in her hair, she was like a radiant flame. There are these dental shops in Bhedasingh with their horrendous wares—hammers and wrenches and pliers and whatnots—near where your husband lives. When she passed by, those dentists came to the doors of their shops to admire her. They teased her, despite their wives looking from the windows above.

‘Sahuni,’

they said—they called her

sahuni

, even though she didn’t operate any shops—’where are you off to so early in the morning, wearing such nice clothes?’

“ ‘

Ooo tyahi samma jana lageko

. I have to buy a thing or two.’

“ ‘And you are leaving poor Masterji by himself?’

“ ‘He is tutoring his students.’

“The wives of these dentists also called out to her, ‘So,

sahuni

, when is the big guest coming?’ Apsara wasn’t showing at that time, but somehow the whole neighborhood guessed, correctly, that the boy was on his way. The eyes of these dental wives followed her as she moved on. They wondered about the Masterji’s family back in the village. They invited Apsara up for tea and sweets and plied her

with questions. She feigned ignorance when the dental wives asked about the wife and sons in the village.”

Since she has been talking for so long, the messenger’s mouth is dry, and she holds on to the hope that Didi will offer her some water. But Didi has already left the window. It’s twilight. The woman thinks she should be on her way back. Drunks appear on the village pathways after dark; there have been cases of rape. Just as the woman is about to turn away from the house, Didi appears at the door.

CHAPTER TWO