Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (25 page)

7. T

HE

P

USAN

P

ERIMETER,

A

UGUST

4

,

1950

Every day in all kinds of ways, Walker’s aide Joe Tyner believed, Ned Almond worked to make Walton Walker’s life a kind of hell. Mostly he took it, but there were the rare occasions when Walker’s anger at his treatment came through. Tyner remembered one occasion when Walker simply blew up. It was a year before the war started. There had been a dinner party at Almond’s house. Just before dinner, Walker took a quick glance at the table and discovered that there was a snub built into the way the seating was done. Military protocol dictated that Walker be seated at the place of honor. Instead, Almond had given it to Lord Alvary Gascoigne, the British ambassador to Japan and a man MacArthur seemed to like. Walker had quickly grabbed Tyner. “Get the car!” he said. “We’re getting out of here!” Tyner, realizing why his general was so angry and seeing the potential for a serious breach that could not be healed quickly, bought some time. “General, I’ve already released the driver,” he replied. Then he quickly found one of Almond’s aides. He explained the problem with the seating and informed him that his general, a very angry general, was about to leave. The seating was immediately redone, and Walker stayed; he had won a tiny battle, albeit in a losing war.

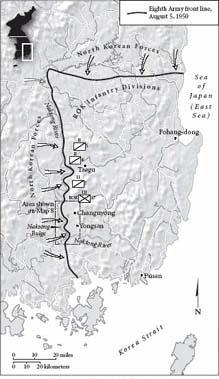

So it was that in those days, as America raced to build up its forces back home, Walker commanded an understrength army that was trying against great odds to slow down a formidable enemy force. As July turned into August, the battlefield began to change, to become one that favored Walker. The In Min Gun were driving the Americans and their South Korean allies into a tiny corner of the country where, with a great deal less terrain to defend, their lines of communication and supply finally started to stabilize. The North Koreans were giving Walker, by dint of their victories, an ever more compact battlefield where he could more readily summon his strengths and exploit his superior military intelligence and American firepower. At the same time, the North Korean lines of communication and supply, hopelessly extended, were increasingly vulnerable to air attack, even as the Americans were pouring more aircraft into the battle. The relentless pounding from American airpower was already taking its toll. Captured Communist soldiers told of mounting shortages of equipment, ammunition, and medical supplies, and experienced troops. Green troops were filling the slots not long ago held by veterans in some elite North Korean units. Day by day, there were still Communist advances, but each victorious moment seemed increasingly pyrrhic in nature.

More elite American and some other UN troops were now also on their way to what was known as the Pusan Perimeter. For the first time, if American troops stood and fought, they would know which units were on their flanks.

The real battle, Johnnie Walker was telling his commanders and his troops in those dark days, was one of trading distance for time, hoping to slow down the In Min Gun until more American and allied troops could arrive. The only question was: Could his shaky, understrength, exhausted forces hold out long enough on this new shorter battlefield for fresher American troops from elite units to arrive, and until—though he did not talk about it—MacArthur made his daring strike, his great gamble at Inchon now scheduled for September 15? In late July, as the last of his units crossed the Naktong River and began to develop positions there, Walker told some of them: “There will be no more retreating, withdrawal or readjustment of the lines or whatever you call it. There are no lines behind which we can retreat. There is not going to be a Dunkirk or Bataan. A retreat to [the port of] Pusan would be one of the greatest butcheries in history. We must fight to the end. We must fight as a team. If some of us die, we will die fighting together.”

Walker himself had been against Inchon as a landing spot: he thought it was too large a gamble and drained too many troops from his understrength defenders. His opposition in some ways sealed his fate with his superior—to be openly against Inchon was to be seen as disloyal to MacArthur, and added to the latter’s contempt for Walker. As much as anything else it was the numbers that bothered Walker: for six crucial weeks, the mission might deprive his already depleted forces, trying desperately not to be driven off the peninsula, of two valuable American divisions, plus much of that supporting air and naval power. Unfortunately for Walker, Inchon was not merely a plan for a breathtaking amphibious landing, it was a test of faith and loyalty, which everyone who served under MacArthur had to take. There was no middle ground. Walker’s position—he favored an amphibious landing at a spot not so far up the Korean shore—was not good enough. His dissent strengthened Ned Almond’s position. Almond became the driving force within the command, organizing the planning for Inchon, fighting off when need be the Navy’s senior commanders, including men expert on amphibious landings who had their own considerable doubts about such a dangerous landing in so spectacularly difficult a location.

Few men pass a loyalty test with such flying colors as Almond did then with MacArthur, or fail it as completely as Walton Walker did. With Inchon, Almond became ever closer to MacArthur, and would in fact, to the surprise (and anger) of the Joint Chiefs, be handed something almost unheard of in the Army: command of the Inchon amphibious force, which allowed him to wear two hats—commander of Tenth Corps, the landing force at Inchon, and chief of staff of the Far East command. Walker, the man whose command had just been split and a large slice of it given over to a sworn adversary, knew that in

some way he had failed in his commander’s eyes. “I’m just a defeated Confederate general,” he said.

While the Inchon planning went on feverishly in Tokyo, the Pusan Perimeter battlefield was turning out to be one of the bloodiest of this or any other war fought by Americans. It would rank right up there with the worst of Civil War battles and some of the terrible island-hopping campaigns in the Pacific. The pressure for victory was mounting on both sides as August began; the Americans rushed fresh forces to the contested, shrinking battlefield, and the North Koreans, aware that they had not, as Kim Il Sung had promised Stalin, gone all the way to Pusan in three weeks, felt the pressure to gain their final victory before the American buildup could take full effect. The American entry into the war had caught Kim by surprise, yet he still continued to overestimate the abilities of his own troops and underestimate the advantage superior weaponry would sooner or later give the Americans, and the hardships it would inflict on his troops. The battle slogans issued by the North Korean leadership to its commanders in the field reflected Kim’s view that the war had reached a critical point. “Solve the problem before August” and “August is the month of victory” became the newest political slogans, and reflected a growing fear that the war might turn into a stalemate or a defeat. But Kim still remained optimistic. His Chinese peers, however, were far more worried. In their eyes, the In Min Gun’s drive south had in the end failed and the tide of battle was about to turn. Kim was still talking victory—while the Chinese were increasingly sure that he had already been defeated. They were far more sophisticated about things like this and had been skeptical of Kim’s leadership from the start. In their mind, not only had the North Korean drive already been stopped, but the Americans were growing stronger, rushing more and better troops into the country along with more equipment. They were about to take the offensive. If that happened, and they were sure it would, then it would involve them in some way.

E

VEN BEFORE THE

Korean War began, the Truman administration had been operating in something of a crisis mode over two main issues. The first and less politically explosive was what a considerable number of the administration’s senior officials believed was a seriously inadequate defense budget, a feeling that America’s recently inherited global responsibilities were far greater than the country’s willingness to pay for them, and that there was a need to double that budget—at a minimum—and quite possibly triple it. So far, the president, a fiscal conservative, had stood against those increases. The other, far more volatile issue was the rapid deterioration of the bipartisan wartime political alliance, along with the decline of Chiang’s China and in time the question of whether someone, in the phrase then being used, had managed to lose China, if a nation can be lost. The issue of China—whether the Democrats had lost it—would hang over not merely the Truman administration but the Democratic Party for the next two political generations.

It was one of the enduring myths of American politics in the 1950s and 1960s that politics stopped at the water’s edge, as if the foreign policy of the United States were some kind of sacrosanct area, separated from and placed above the normal meanness and conflicting interests of domestic constituencies and the passions they engendered. Nothing was further from the truth. There had been considerable (if, on occasion, reluctant) bipartisanship during the war years, a bipartisanship that was in some ways involuntary, given the very considerable dangers posed by Germany and Japan, but it began to unravel almost as soon as the war ended. If anything, that very quality of wartime suppression, in which one party, out of power for a generation, had felt both voiceless and powerless, created a political force all its own and would finally lead to a serious, if belated, backlash against the party that had ruled for so long. There is no way to understand the mean season just beginning in American politics, and which formed the critical political backdrop to the Korean War—one wing of the opposition political party accusing the principal architects of both America’s victorious war effort and its postwar foreign policy of acting in concert with the country’s

enemies—without grasping the totality with which Franklin Roosevelt had transformed the political landscape during his singular four-term presidency, and thus the degree to which his economic and social revolution had transformed the country and, momentarily at least, marginalized the Republican Party.

Part of what had swept the Republicans away as a majority party was the sheer charismatic quality of Roosevelt himself and his extraordinary ability, far ahead of any other major politician in the nation, to exploit the newest technological instrument of the era—radio. His mastery of radio, his ability to use it in the most intimate manner imaginable to reach the electorate, had proved a stunning political asset. With it he transformed the very nature of the presidency by creating a direct, previously unknown emotional connection to the populace. No longer was the president an aloof figure, formal, distant, and unreachable, a man in some stiff, uncomfortable pose in an occasional photo in a daily newspaper; now there was a new one-way intimacy; in his new incarnation he was a friend of ordinary people, a warm and caring political figure who made house calls over the airwaves, as attuned to the needs and fears of Americans as the favored family doctor, who also made house calls. He did not, it appeared, even need to make speeches—rather they were called fireside chats.

My friends,

was how he would begin one of his radio talks, and as he did, he forged a brand-new connection with millions of voters. He was, in essence, the first media president, the creator of what became known as media politics, which would some thirty years later produce a television presidency.

The cumulative effect of the man—his voice, his unmatched political skills, the bitter Depression that had plunged so many Americans into misery and had catapulted him into office, his seemingly revolutionary New Deal economic and political programs, and of course the galvanizing effect of World War II—simply overwhelmed the Republicans, who had been associated with the forces of the very rich in an era of economic catastrophe. No other American president had served more than two terms, but Franklin Roosevelt, because of the special confluence of very different forces, had run four times and won. His New Deal legislation empowered the more vulnerable in the society and made unionization easier in the workplace. With that he became the head of a political party sympathetic to the needs and rights of labor in what was still very much a blue collar economy. He strengthened his hold on the country thanks to the political leverage offered by the approach of global war during the 1940 campaign, which helped give him his third term, and in 1944, as a wartime president, he won again, despite severely failing health, his physical decline carefully masked from the people. The combination of

two

transcending events—depression and war—had meant he could extend his remarkable

hold on the political scene long after the moment when, in normal political times, his fortunes would certainly have begun to ebb. To the Republicans, by 1944, it seemed that he had been president forever and might remain president forever. By the time of his third run, the approach of a world war had not only severely damaged the opposition party, but made it somewhat schizophrenic. Roosevelt, after all, was an internationalist, gradually preparing the nation for entry into a terrifying new global conflict, most assuredly on the side of embattled England, the nation’s closest ally.

On such matters, the Republican Party was badly split, caught in divisions that were deep, unhealable, and profoundly geographic. Part of its leadership represented a wing of the traditional internationalist elite, reflecting the views of Wall Street and State Street financiers, transatlantic men all. They believed that, like it or not, America could not sit on the sidelines in such a war, that it must choose—and must choose the side of the Western democracies. That placed much of the Republican leadership in the position of endorsing Roosevelt’s internationalism or supporting a slightly more conservative figure who seemed on many of the great issues of the era to sound very much like the president himself. But the other wing of the Republican Party was very different: it was essentially more grassroots; it reflected old, abiding, small-town American isolationist fears of being pulled into the constant squabbles and wars of a corrupt Europe, and worse, doing it for the British. These feelings were rooted primarily in the Midwest, where among the governing circles in many small towns and cities there was a fundamental hatred of almost everything Roosevelt was doing on the domestic scene, of his New Deal, which these critics passionately believed was, to use their favored word, socialistic. Within the party, this isolationist wing might well have been numerically greater than the internationalist wing, and it was surely significantly more influential at the local level, but it had lost out to the Eastern elite, the internationalist wing, at the 1940 convention, principally because of the rise of Hitler. Wendell Willkie, the barefoot lawyer from Wall Street, as he was called, was nominated, a major triumph of the internationalists. That had been bad enough, but the small-town Midwestern wing, the people who

knew

that they were the real Republicans and that the party should be theirs, and that their values were the truer ones because they were the more

American

ones, had lost again at the convention in 1944, this time to Tom Dewey, the governor of New York, and would eventually be beaten once more by Dewey in 1948. To the core Republican leadership in the heartland, the voice of their presidential candidates in all those elections had sounded too much like that of men unable to separate themselves from the Democrats, a thin echo first of Roosevelt and then of Truman. “If you read the

Chicago Tribune

, you’d know I’m a direct lineal descendant of FDR,” Dewey

once said of the paper that was the central media instrument and voice of the isolationists.

While that amazing Roosevelt run had taken place, the Republican right wing had raged impotently. The more it lost, the angrier it became. Each time, its representatives had come to the national conventions confident of their greater truths, only to see the nomination hijacked by an elite from the big industrial states backed up by a few powerful internationalist publishers, most notably Henry Luce, the head of

Time

and

Life,

a man then at the very peak of his media power. The residual bitterness from the 1940 and 1944 conventions was very real; it was hard to tell who the right wingers were angrier at, FDR and the Democrats or the internationalist wing of their own party. To them, the internationalists were fake Republicans, Eastern snobs, who had just enough skill to steal the nomination but never enough to win an election.

With World War II over and Roosevelt dead, the right wing finally believed it was regaining power, both within the party itself and nationally. The 1946 off-year election had given the right-wingers their first chance to strike back. Their cause, as they saw it, was nothing less than simple Americanism, or the protection of an America of sturdy old-fashioned values, which had produced people exactly like them, against the America of their enemies, which had produced people who favored what they saw as socialism or Communism or, in their minds, people whose lives were too heavily subsidized by the government. “The choice which confronts Americans this year is between Communism and Republicanism,” said B. Carroll Reece, the Tennessee congressman and chairman of the Republican Party, just before the election. Nebraska’s Senator Kenneth Wherry added: “The coming campaign is not just another election. It is a crusade.” And in some ways, and in some parts of the country, it was nothing less.

Harry Truman, the accidental president, the unlikely heir to the mighty Roosevelt presidency, was probably lucky indeed that 1946 was

not

a presidential election year, given the general unhappiness in the country, and the anxieties that lay just under the surface. Unlike its allies (and enemies) whose lands lay in ruins, the United States had emerged from the war as the sole global economic powerhouse, a nation rich in a world that was poor, its allies and adversaries alike ground down by fighting suicidal wars twice within twenty-five years. America, protected in that era by its two great oceans, untouched on its mainland by enemy bombs, had emerged infinitely more muscular than when it had gone in; the country had been dragged by exterior forces, kicking and screaming, to the zenith of its power. But there was a surprising degree of anxiety as well as stored up resentments just underneath the surface, most notably over dealing with the increasingly difficult and complex peace that the United

States had inherited and over accepting the great jump in global responsibility that came with the peace. The new threat of Soviet Communism—the fact that an ally had suddenly become an adversary—was just beginning to fall over American politics. To some of those who had been out of power there was little surprise in this—the Soviets had been an unlikely ally in the first place, and to some of them the war had been the wrong one from the beginning; we had once again fought to save the British. With the war over, not that many Americans were eager to take on these great new unwanted international obligations—and risks—that went with becoming a superpower and replacing imperial Britain as the leader of the Western alliance, nor were many necessarily thrilled to become, as the architects of foreign policy in Washington seemed to be demanding, part of Europe’s endless political-military struggles on a long-term basis. Many Americans wanted less, not more, of a connection with the European democracies.

And so the Republicans did very well in the congressional election of 1946. The wartime pressure to support the incumbent president—don’t change horses in midstream—had been a very successful Democratic slogan, but it was gone. The Republicans, running on a program of a 20 percent across-the-board tax cut, gained eleven seats in the Senate and fifty-four in the House. The Roosevelt coalition of Northern labor unions and big city machines combined with conservative Southern oligarchs looked like it might be coming apart, replaced by what the Republicans hoped was a return to old-fashioned American normalcy. “The United States is now a Republican country,” said Senator Styles Bridges of New Hampshire, soon to be a major player in what would be known as the China Lobby. Some of the newly elected Republicans had campaigned not so much against the Democratic Party as against Communism and subversion. The election added to the party’s senatorial ranks Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, Bill Jenner of Indiana, John Bricker of Ohio, Harry Cain of Washington, and James Kem of Missouri. Some of them, joining up with conservatives already in the Senate, like Kenneth Wherry, were to turn out to be obsessive on the subject of Communists and subversion in our own government, a wonderful new issue that tended to neutralize their vulnerability on economic matters. “Bow your heads folks, conservatism has hit America. All the rest of the world is moving Left, America is moving Right,” wrote T.R.B. after the election in

The New Republic,

then a traditionally liberal magazine.

In play was nothing less than the issue of America’s role in the postwar world. Was it willing to accept the global leadership of the Western democracies? And how much in terms of sheer dollars—in terms of taxes—would this cost? On this issue the leadership of both parties was uncertain. Neither party

was in any rush to pay the economic price demanded of a nation that was going to lead the West. The Republican Party, the more virulently anti-Communist, was, if anything, in a greater rush to disarm, more willing to depend on the nation’s nuclear monopoly, and warier of accepting a role in building up a badly damaged Europe, one dangerously vulnerable, it was believed, to internal Communist subversion. The truth was that on the eve of the Korean War, America’s defense posture was a shambles. Its defense budgets had been slashed; its armed forces were far too small; and its weaponry and equipment—the most advanced in the world only five years earlier—was increasingly inferior. The top people concerned with what was already coming to be known as the country’s national security were seriously divided over how much was enough. At the moment that the North Korean Army crossed the thirty-eighth parallel, Secretary of State Dean Acheson, already under virulent attack from the Republican right wing for being, as it was said, soft on Communism, was trying as deftly as possible to maneuver a new, dramatically elevated commitment to defense spending through the bureaucracy. Though Acheson had already become the most influential member of the president’s top national security team, by no means was this attempt a guaranteed success.