The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (63 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

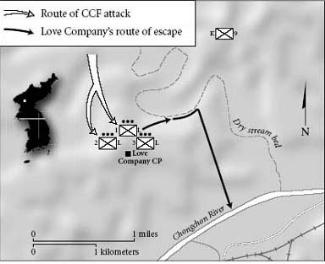

They were quite far east, almost the farthest east of any unit of the Eighth Army, except for King Company, which was supposed to be a mile and a half east of them. There were about 170 men in Love Company when it was hit, about forty-five of them in Takahashi’s platoon. King Company was probably the same size. Farther east, protecting the eastern flank of the Eighth Army, was a South Korean corps. When Takahashi and the other junior officers had been told at one of their final briefings that the ROKs would handle their right flank, a lot of eyes were raised to the ceiling. To the men who had been doing the fighting over the last three months, it could all too easily mean an instantaneous collapse and then a virtual highway leading directly into their own units. It was one of the many issues that divided the Dai Ichi, where men did the planning, from Korea itself, where men did the fighting.

A lot of things made Takahashi uneasy that night. First off, they could not make contact with King Company. It was supposed to be out there, in the vast, wide-open, unexplored dark space that abutted them, but they had no radio connection and the patrols they had sent out had not made any contact. That of itself was shocking; it meant a large enemy unit could easily slip between them—if King was out there at all. Later, Dick Raybould heard that the Chinese attack came through an area where King had placed an outpost of three men; those men, he was told, seeing how many Chinese there were, had not fired, fearing they would be killed instantly. So no warning shots were heard.

At about 8

P.M.

, two Asian soldiers rushed into Takahashi’s platoon area with their hands up. They seemed in a panic and were shouting a few words of broken English about a huge army headed that way, some of them apparently on horseback. Slam Marshall later wrote that the two men were ROKs, but Takahashi always believed otherwise. They were wearing quilted uniforms of a kind he had never seen before, and there was the language problem: most Koreans spoke a good deal of Japanese, having lived under their colonial regime, and that gave Takahashi relatively easy linguistic access to them; but these men did not speak Japanese. They seemed to be communicating in some kind of international sign language. They were telling Takahashi’s men to get out, that

they were all going to be killed. It was very disquieting, and later Takahashi decided they were Chinese soldiers trying to panic his men.

Takahashi was sure by then that they were going to be hit, and that it would come from his left, and he shifted his machine guns accordingly. The attack began around 11

P.M.

After the first burst of firing, a voice yelled out, asking if they were King Company. It was the Chinese, Takahashi was certain, speaking English. Apparently they had confused the two companies. Then the big attack came. His own men, Takahashi realized from the start, were very badly outnumbered. Later it was believed that at least a Chinese battalion, and quite possibly a regiment, had struck at exactly the point where his Second Platoon was positioned. The Chinese overran their position quickly. What was terrifying was not just the fact that so many Chinese were coming right at them, but that they could hear the sounds of so many others going right past them, and knew therefore that their escape routes were being cut off. Takahashi had a good man on a machine gun to his left, a sergeant named Bly, and he knew it was hopeless when Bly yelled that he couldn’t hold his position. “There’s too many of them!” he shouted out.

From the moment the battle began, Takahashi never spoke with another officer from Love Company. He knew he was absolutely on his own. If they were going down, he decided, they would go down as a unit. That was where Dick Raybould, who had met Takahashi only the day before, first saw him in action, and he was deeply impressed: here was a brave, steady officer trying to rally his men in a hopeless moment. What impressed Raybould was how cool Takahashi was. Neither of them knew that Captain Vails had already been hit and was probably dead. All Raybould could see was this slim little man trying to rally a doomed unit. “Fall back on me! Fall back on me!” he kept shouting. “Hold together! Rally on me!” It was what a born leader does in the worst of times, Raybould thought. Takahashi’s platoon was virtually destroyed, but amazingly enough the few men left from his platoon and some from other platoons were following him, retreating to a higher point on the mountain. Takahashi was aware that he was losing men by the minute, but at least they were making a stand. They had held that position for probably a little under an hour, and then they fell back to higher ground. There his men and the men from the First Platoon made their last stand.

13. C

HINESE

A

SSAULT

O

N

L

OVE

C

OMPANY,

N

OVEMBER

25–26, 1950

It was as if they had been assigned not so much to a battle but to a fate. To hold the Chinese off any longer, they would have needed a lot of grenades and flares and a lot more ammo. Sergeant First Class Arthur Lee, a platoon sergeant and one of Takahashi’s best men, was handling a machine gun just to his left. If Takahashi was going to die taking on what appeared to be the entire Chinese Army, he was glad it was next to Lee. They nodded to each other, the nod seeming to acknowledge that they were both going to die up there, but at least they were going to die like soldiers. They were trying to talk, and to pinpoint the precise place where the Chinese were located, when suddenly the only sound coming from Lee was a gurgle. He had been hit in the throat and was drowning in his own blood. The others fought on, and the Chinese made charge after charge, getting closer to their little knoll all the time, until they finally pushed the Americans off the hill. Almost every man was killed. They had held out against fearsome odds for several hours, but Love Company, which had been a good, solid, competent unit the day before, was gone. Takahashi told the handful of men left to get out as best they could. He tried to lift Lee, but he was already dead. Later, Takahashi and Raybould understood that Love and King companies had been on point not merely for the division, or the corps, but for the entire Eighth Army, and had taken the full brunt of the Chinese attack, that holding the Chinese off for a few hours had been something of a miracle, and it was hardly less of a miracle that anyone made it out of there alive. But that understanding, with the small amount of mercy it offered, came much later.

The final glimpse Raybould had of the fighting on top of that mountain was of Chinese soldiers tackling the last remaining Americans. Raybould tried

to take some men with him, but most of them wanted to follow a softer part of the incline that led down the mountain. Raybould was sure that was where the Chinese would be waiting, so he slipped over to a place where the drop was much steeper. The key to surviving, he kept telling himself, was to take his time, not panic, descend slowly, and never give an enemy soldier a silhouette. He eventually met up with some stragglers from King Company and made it back to the Chongchon.

Gene Takahashi was trying to get down the hill when four or five Chinese soldiers surrounded him and took him prisoner. First they took his watch and his cigarettes. He tried to argue for the watch, a graduation present from his mother, but one Chinese soldier put a gun to his head, ending the argument. Then they indicated through sign language that he was to shout out to bring in other prisoners. Takahashi did—shouting in Japanese for others not to come in. Next they took him back to their battalion headquarters. There everyone seemed fascinated by a man with Oriental features wearing an American uniform. He seemed to make them nervous; perhaps he represented a sign that Japan was entering the war. By that time they had also captured Clemmie Simms, the company master sergeant, a strong, highly professional NCO, the very core of a professional Army, who had, Takahashi remembered, only three months to go before retirement.

Later, it would strike Gene Takahashi that he was the rarest of men, someone who had been imprisoned in wartime by two of the greatest nations in the world, the United States and China, though the Chinese imprisonment was quite brief. The Chinese started marching Simms and him away from the battle, probably heading them north. Fearing they might be shot at the foot of the hill, they tried to work out signals for an escape. He started singing a recruit’s cadence song, a kind of early rap song, substituting for the usual words instructions on how and when to break away from their captors. At the right moment Simms jumped his man, Takahashi pushed his, and they made their break. As he ran, Takahashi heard gunfire near where Simms had been. He did not see Simms again. Eventually, long after the war was over, Simms’s name did show up—on a list of men who had died in a Chinese prison camp in March 1951.

Gene Takahashi was confused and frightened because he was behind Chinese lines—and he was ashamed of himself as well because he had lost so many men and then had been captured. He moved cautiously and carefully, only at night, until he finally bumped into American troops near Kunuri two days later. There he found the rest of his unit, but there was almost nothing left of it.

WHAT BRUCE RITTER

remembered from those days was how the sheer terror of the Chinese assault could open up and reveal what was inside a man in a way that no man should ever be opened up. It was like peering inside another man’s soul: all the bravado and the veneer were gone, and all the things that most men like to hide from those around them were all too nakedly there for inspection. Some men he fought with behaved with valor and honor in those crucial moments, far beyond what anyone had a right to expect, risking their lives, for instance, to carry off wounded men they had never met before; while a platoon leader who had seemed a perfectly decent officer melted down right in front of him, in a moment of total cowardice.

Ritter was a radio operator with Able Company of the First Battalion of the Thirty-eighth Regiment, which was also part of the Second Division. His was a difficult, exceptionally dangerous job. The North Korean snipers liked to single radiomen out; they had killed three in his unit in a short space of time. The radio had a long antenna, a beacon of sorts for the enemy, invented, it seemed to Ritter, only to signal to their best shots exactly where fire ought to be concentrated. His fellow soldiers always tended to keep their distance from him. Ritter was sure that he was not put on this planet to carry a radio; he was five-ten and weighed 120 pounds at the time. The 300 radio he carried was heavy—it weighed, they liked to say, thirty-eight pounds at the beginning of the day and about sixty by the end. Ritter was twenty-three at the time, having celebrated his birthday a few weeks earlier, during the battle of the Naktong, and still a lowly PFC; promotion had come all too slowly, in part, he suspected, because he was so skinny that he just did not look like much of a soldier. He had done an earlier tour in the country, spoke some of the language, and could be thrown into the breach as a minimalist interpreter. But about the time a company commander discovered how valuable he was, the officer would either be killed or promoted.

On that first day of the offensive, most of the division was back at Kunuri, and he figured his reinforced company, perhaps 230 men, was about twenty-five miles to the north. Their jumping-off place had been a village called Unbong-dong. They were supposed to go about six miles over two days to Hill 1229, more a mountain actually. But they had been taking fire from the middle of the first day and that had slowed them down. They had been short a rifleman, and so Ritter had been turned into a rifleman, not a radio operator, and his chances of living had increased exponentially. About a third of the way to their objective, the incoming fire got so heavy they stopped and took up a position on the back side of Hill 300. The ground was frozen hard and their foxholes were neither deep nor well dug. They began rotating in one-hour shifts—an hour’s sleep, if you were lucky, followed by an hour on watch. They

were the extreme edge of the division, with the battalion strongpoint about three miles behind them.

When the Chinese struck near midnight—shocking them with the blowing of bugles, the shrillness of whistles, so many enemy soldiers suddenly right in their midst—the company managed to hold for about forty-five minutes before the retreat began. Moving back was hard; it was the worst of conditions—nighttime, with a great many wounded to carry out. Ritter remembered slipping back to another hill and someone trying to set up a perimeter, but there were too many Chinese, and once again they had to pull back. He thought perhaps another forty-five minutes had passed, and their losses were grievous.

They began to straggle back after that to where they hoped the battalion was. By then he was part of a makeshift unit, perhaps twenty or twenty-five men from different companies. Ritter knew no one in his new group, and it was unclear if anyone was in charge. Scenes like this were taking place throughout the Eighth Army that night. In the chaos, stumbling back in the dark, the sounds of the Chinese weapons ever closer, Ritter found himself with an even smaller group, four Americans and two KATUSAs, carrying one wounded soldier on a blanket with no handles and thus no good way to grip it in the terrible cold.