The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (73 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

His cables were now full of the most pessimistic of predictions. Unless he got vastly more troops, his forces would soon be forced to withdraw into beachhead bastions. The Chiefs were unnerved by the rising tone of pessimism—indeed panic—in these cables. Bradley later went through some of them, angrily writing comments in the margins, and added quite bitterly of that period that MacArthur had “treated us as if we were children.”

THE ENTRANCE OF

the Chinese and the terrible UN defeats in the North did not make America more cautionary. Rather it sharpened the existing political divide, made the China Firsters more hawkish, cast few doubts among the faithful about MacArthur’s decisions, and subjected the administration to even more pressure, sending Truman’s popularity spiraling still further downward. For those in the China Lobby it was absolute proof that American policy in Asia had failed; to Henry Luce it showed that he had been right on China all along as Acheson had been wrong. Now perhaps, Luce hoped, the administration would be more resolute in Asia. As one of Luce’s biographers, Robert Herzstein, wrote, Luce had always seen Korea not “as a police action, or a quagmire, but as one promising front in the war to liberate China.” Now the publisher was more aggressive than ever. John Shaw Billings, a senior Luce editor who kept a careful record of Luce’s thoughts and feelings, noted in his diary on December 5, even as the rout from Kunuri was still taking place, “Luce wants the Big War, not now perhaps, but sometime.” Luce was more convinced than ever that his vision of a major confrontation in Asia was right and that Communism could be rolled back—if the administration did not get in the way. At the same time, as their belief in the eventual and inevitable confrontation between the Communists and the West grew more certain, Luce

and some of the senior people around him began to worry about the location of their offices, just in case the Communists dropped an atomic bomb. The Time-Life offices were about two miles from Manhattan’s Union Square, considered the city’s atomic epicenter. There was serious talk of moving the headquarters several miles farther away to Manhattan’s Upper West Side, and some people even talked about moving the headquarters to Chicago. Nor eventually did MacArthur’s weak showing before the joint Senate committees affect Luce, who wanted to make him

Time

’s Man of the Year for 1951 but was talked out of it by his editors.

A NUMBER OF

the men who were part of decision-making in Washington remembered the weeks that followed the Chinese entry as the darkest period of their governmental service, a moment of paralysis. They were under constant attack, and the man who should have been helping out and leading the resurgence of their military forces had become their leading critic. Every bit of news, it seemed, was bad. There was a horrible vacuum in leadership and no one in Washington seemed to be able to fill it.

Particularly upsetting was the fact that these were not the flawed troops the United States had thrown into Korea back when the war began: these were the best the country had, and yet they had been hammered badly; and now the Americans were fighting the most populous nation in the world, whose underarmed forces suddenly seemed invincible. It was a horrendous equation: the war was much bigger, the enemy more powerful, the domestic political support for it greatly diminished, and becoming slimmer by the day. In general, those who worked in that administration are now regarded as among the ablest men of a generation. The phrase “The Wise Men” has been applied to them in the title of an admiring, best-selling book. But all of them, even as they had sensed during October and November that something terrible was about to happen, had been silent, frozen in place, while MacArthur continued to stretch his orders. They and the civilians who had gone to Wake Island had never asked MacArthur the tough questions when it mattered, in no small part because the political tide was moving away from them. They, who had never trusted him, had acted as if he were some kind of prophet, authorized to speak not merely for his own command but for the Chinese commanders as well. Now, as he unraveled in Tokyo, they once again seemed powerless to do anything about him or the command.

It was not just the Joint Chiefs and the senior political people like Dean Acheson who failed to restrain MacArthur at that juncture, it was also the most respected public official of the era, George Catlett Marshall, who had just

moved over after an enviable tour as secretary of state and an all too brief retirement to become secretary of defense. Of the senior group, he was the most knowledgeable and experienced, an icon of icons, more like a father figure than a peer to most of the men serving Truman. He was the quietest and most modest great figure of an era: he never raised his voice, never gave angry commands, never threatened or bullied people. His strength came from his sense of purpose and duty, which were absolute; his almost unique control of his own ego; and his ability to separate what mattered from what did not. Because of his awesome self-discipline and stoic personal qualities it was easy to underestimate Marshall’s full value. He was often seen as being primarily skilled as a great management man, and what he did

not

get credit for was his sheer intellectual firepower, something he was quite content to mask. George Kennan might have been a more classic example of a gifted intellectual figure working in a bureaucracy, and Acheson, with his cutting wit and his formidable verbal skills, a more forceful figure in any public debate, but Marshall quietly possessed a rare mind of uncommon intellectual strength, with an exceptional sense of the consequences of deeds. In some ways he was self-taught during that long and difficult career, but he had used every position he ever held, no matter how lowly and disappointing, to understand the forces at play around him. What he had come up with was the rarest of things, and the hardest thing in the world to seek, and that was wisdom. His was the most pragmatic kind of intelligence, never flashy, and he always made clear that a deeply held sense of duty was more important than sheer brilliance; far fewer men talked of Marshall’s brilliance than they did of MacArthur’s, but in a quiet, reserved way, Marshall tended to get the larger forces of history at play in his era right, as MacArthur often did not. His decline in that period was a grievous loss for the Truman team.

At this critical juncture, as in the days after Unsan, Marshall was surprisingly passive. It was probably his weakest moment in a long and distinguished career. Why he failed puzzled some of the others. Perhaps, thought some of his admirers, his long and unhappy personal relationship with MacArthur, one that went all the way back to World War I, was part of the problem. Perhaps, they thought, Marshall was a little more loath to set limits as he might have for another officer, for fear of becoming the caricature that MacArthur had created of him. But it had to be more than that. Was it the very nature of the job itself as Marshall saw it—that the job of secretary of defense was to support the commander, or the uniformed Chiefs, and not to impose his own will on men in uniform? In effect, did it mean that he was much freer to stand up to MacArthur when he was a senior figure at State than when he was at Defense? Or was he

uneasy about usurping the powers of the Joint Chiefs? Had, in effect, his very strength, his modesty, his sense of a proper hierarchy, become a weakness? Certainly that was part of it. But finally it is important not to lose sight of the fact that the George Marshall of 1950 was not the George Marshall of World War II, that the crushing hours and burdens of both the war and the postwar era had taken their toll, that his health was slipping and he was simply not as strong a man physically or intellectually as he had been in that earlier incarnation. What made it worse was his standing among them: they instinctively deferred to him, took their signals from him, and now there were no signals.

MacArthur’s mood swings, some of the Washington people thought, were reflected in his estimates of the size of the Chinese forces facing him. Typically, he had gone almost overnight from grave underestimation to significant overestimation. The numbers he and Willoughby liked to use for Chinese troop strength before they struck were piddling, perhaps sixty thousand in country. Now MacArthur told Joe Collins, who had come to visit him, that he faced

five hundred thousand men

on the battlefield and his airpower was hamstrung in dealing with them because of the Manchurian sanctuaries.

The impotence of Washington angered one senior officer, Lieutenant General Matt Ridgway, more than all the others. He had been uneasy with MacArthur’s drive north from the moment it began. The dangers were too great, the ordinary infantrymen placed at too much risk. There seemed to be too little thought of the consequences. Now, with the front collapsing on them, the troops still at risk, and no clear strategy at hand, Ridgway was appalled by the failure of MacArthur to rise to the occasion. He was equally appalled by the lack of purpose and command in Washington, the willingness of the men one rank above him to be part of this strange vacuum of leadership.

Of all the senior military men in Washington, Ridgway became the most outspoken as MacArthur seemed to unravel. Ever more bad news kept coming in, and no one in Washington was standing up to take charge. The Joint Chiefs continued to make the most tentative suggestions to MacArthur, who treated their recommendations with complete contempt, while demanding more and more troops—he seemed to want four additional divisions, divisions they simply did not have. The good thing about the success of Inchon, they had all believed just a few weeks earlier, was that they were going to get a division back for Europe. The last thing they wanted, with American military strength stretched so thin elsewhere, was to pour more troops into the Korean theater. “We want to avoid getting sewed up in Korea” was the way George Marshall had once noted it at a meeting. Then he added the crucial kicker: “But how could we get out with honor?”

There were, Ridgway thought, too many meetings where nothing was being

decided, where everyone was sitting around waiting for someone else to do something. The other generals, Ridgway wrote, were still “in an almost superstitious awe of this larger than life military figure who had so often been right when everyone else had been wrong.” On Sunday, December 3, the senior national security and military men, including the Joint Chiefs, Acheson, and Marshall, all sat through yet another long meeting where, in Ridgway’s mind, they were once again unable to issue an order, to correct, in his words, a situation going from “bad to disastrous.” Finally, Ridgway asked for permission to speak and then—he wondered later whether he had been too blunt—said that they had all spent too much damn time on debate and it was time to take some action. They owed it to the men in the field, he said, “and to the God to whom we must answer for those men’s lives to stop talking and to act.” When he finished, no one spoke, although Admiral Arthur Davis, who had replaced Al Gruenther as the director of the JCS staff, handed him a note saying, “proud to know you.” Then the meeting broke up. Ridgway started talking to Hoyt Vandenberg, the Air Force chief of staff, whom he had known since he was an instructor and Vandenberg a cadet back at West Point.

“Why don’t the Chiefs send orders to MacArthur and tell him what to do?” Ridgway asked his old friend.

Vandenberg shook his head. “What good would that do? He wouldn’t obey the orders. What can we do?”

At this point, Ridgway, in his own words, simply exploded. “You can relieve any commander who won’t obey orders, can’t you?” Ridgway would never forget the look on Vandenberg’s face: “His lips parted and he looked at me with an expression both puzzled and amazed. He walked away then without saying a word and I never afterward had occasion to discuss this with him.”

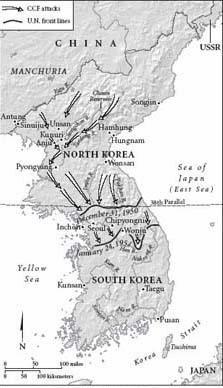

IN THE MEANTIME,

MacArthur’s army was in full-scale retreat. The Big Bugout, some called it. The retreat covered some 120 miles in ten days, even though the Chinese, momentarily at least, had little offensive capacity to press any advantage. That rush south represented the total disintegration of a fighting force, as Max Hastings wrote, “resembling the collapse of the French in 1940 and the British at Singapore in 1942.” They were fleeing, one British officer wrote later, “before an unknown threat of Chinese soldiers—as it transpired, ill-armed and on their feet or horses.” As the surviving men of the Second Division pulled back, they passed huge bonfires visible from miles away, as vast stores of equipment, supplies that had still been coming into the country when the great offensive started, were destroyed, lest the gear be captured by the Chinese. Some of the men were still in their summer-weight uniforms, and hearing that winter uniforms, which had finally arrived in country, were being burned, they tried to get near the stores of equipment, only to be turned away at gunpoint by MPs.