The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa Collected Works: Volume Two (74 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa Collected Works: Volume Two Online

Authors: Chogyam Trungpa,Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

That’s how it actually begins with the ego situation as well. You exist; therefore I exist, to begin with, very simply. And the reason we know you exist is because we have no idea at all! The first thing is that you don’t exist; therefore others exist first. Ladies and gentlemen, I don’t want to confuse you further, nonetheless it is quite a tempting discussion. When others exist, that is what you see first, before you realize you are there. Before you think you are there, you begin to see other very strongly. And then, since there is other, there are possibilities that the other should be conquered, subjugated, or seduced. So those two possibilities of aggression and passion begin to develop. And the third possibility is that, when others exist, and you think you can’t match your fund with them, then you just ignore them completely, totally. Then ignorance begins to develop. “Couldn’t care less” begins to develop. So those three possibilities—passion, aggression, and ignorance—begin to develop. We begin to feel that we have something substantial to hold on to. That is what’s known as ego, so-called ego, which is based on a snowballing situation. There is nothing really such as ego, but there is a somewhat fictional idea of some kind based on reference point. Because of other, we begin to develop our selves. Therefore we begin to reject possibilities of gentleness and to develop one-up-manship, aggression, and what’s known as “macho-ness,” egohood. We begin to impose our possibilities of power over others: that when you see red, you should conquer the red; when you see blue, you should seduce the blue; and so forth. We begin to develop that particular system, which is completely unnecessary.

In turn, we begin to develop the notion that the sky, or heaven, is not vast enough. We begin to regard heaven as a pie, which we think we can cut up into pieces, eat it, chew it, swallow it, and taste it. In turn, we begin to shit it out, so to speak. So we cease to have greater vision of heaven altogether, sky altogether. Therefore we begin to fix our existence, based on either passion, aggression, or ignorance.

In order to overcome such egomaniac possibilities, we are talking in terms of developing greater vision. Nonetheless, in order to overcome ego, we have to undo our habitual patterns, which we have been developing for thousands of years, thousands of aeons, up to this point. Such habitual patterns may not have any realistic ground, but nonetheless, we have been accustomed to doing dirty work, so to speak. We are used to our habitual patterns and neuroses at this point. We have been used to them for such a long time that we end up believing they are the real thing.

In order to overcome that, to begin with, we have to see our egolessness. That’s quite a lengthy discussion we might have later on: seeing the egolessness of oneself and the egolessness of other, and how we can actually overcome our anxiety and pain, which in Buddhist terms is known as freedom, liberation, freedom from anxiety. That is precisely what nirvana means—relief. So as we will discuss other possibilities further, particularly the four types of obstacles, I would like to stop here. Maybe we could have some discussion. Thank you very much.

Question:

Sir, you mentioned that first there’s ego of other, and then ego of self develops. But don’t they arise simultaneously?

Vidyadhara:

Not necessarily. First there is other. It is like when you wake up in the morning. The first thing you are woken up by is the daylight. And if you fall in love with somebody, you see your sweetheart first; after that you fall in love. You don’t just fall in love to begin with, because you don’t have anyone to fall in love with. So there is always

other

to begin with; then you have your things going after that.

Q:

Well, how is it then that to realize egolessness of other, you work backward from the egolessness of oneself?

VCTR:

That’s because you have done the whole thing already. Therefore you begin to realize you are the starter, not necessarily from the point of view of logistics, particularly, but that you have a strong hold on the whole thing. You fall in love with somebody, the other; therefore you are as much in love with yourself. Therefore we start with

here

, to overcome other. It’s very basic and very ordinary. In other words, if you are not supposed to take sugar, you see sugar first, but then

you

stop taking it, which starts with you, right?

Q:

I guess I just feel that there has to be some sort of echo, some sort of trace there, even to react to other.

VCTR:

Well, in any case, that’s the point you perceive first: so first thought is other; second thought is this. Next the action is

that

, and then after that,

this

, which goes back and forth many times. But the first and only way to stop is to stop

this

.

Q:

Rinpoche, I’d like to ask a question about last night’s talk. When you spoke of basic goodness, fundamental goodness, and then went on to say that without white there’s not black, without blue there’s no red, and developed that dialectic; well, how about basic badness—the opposite of goodness? That brings to mind the Christian mystics’ belief, Thomas Merton and others, of a basic sort of badness—original sin.

VCTR:

That’s very interesting. When we talk about basic goodness, we are not talking about good as a goody-goody principle, but we are talking about the application and possibilities of fertility of any kind. Before even the notion of good or bad happens at all, there is basic goodness, which allows things to happen, allows things to manifest in their own right or at their own best. The basic point of the Catholic tradition of original sin and punishment, I regard as purely a teaching technique, rather than a presentation of totality or an evolutionary principle, particularly. I could quite safely say that the notion of original sin came about at the beginning by people being told that “You are made out of the image of God himself.” There are a lot of possibilities of going wrong with that, taking lots of pride and arrogance in that: “I’m made out of God.” Nonetheless, even though you are made out of God, you do something wrong. So there is original sin, first sin, which comes from arrogance. That seems to be fine.

Q:

Sir, when you were speaking of there being nothing—I think you said—the first thing was

other

, and then because of that, we have a sense of self. Is that still simple perception at that point, before you get into some kind of reverberation or echo back and forth? Is that the ego part or is it already ego at that point?

VCTR:

At the beginning? I don’t think there is any ego at the beginning at all. When we first perceive the other, even then there is no ego. But then you begin to perceive

yourself

because of the other—that is the beginning of ego.

Q:

Is it when you begin to perceive yourself, at that point?

VCTR:

Perceive oneself, yes. Linguistically, it goes: “am . . . I.” “Am” is the other, “I” is me, which is a question, as we use the English language—“Am I?” that actually works quite fine with that principle. So first is “am.” “Am what?” You may be able to liberate from that without saying “Am I?” Then you have just “am.” After that we become “I.” “Am

I

good?” “Am

I

bad?” It begins with a question, which is very interesting from the logic of philology, how the English language actually developed.

Q:

Sir, I just wanted to ask when that happened, because there are all kinds of implications for children, for babies. Are you saying that that happened at some time in our development, or before we were born?

VCTR:

Well, we can’t actually make sure children don’t have ego. That’s part of education. You have to have education and children have to have ego. We can’t actually make sure that children are egoless. That goes along with a natural process. They have to learn to say, “I” and “no” and “yes.” I think we can’t do anything very much about that.

Q:

But that state before recognizing

other

, is that something that we’ve ever had as people after we were born?

VCTR:

Well, as soon as the child sees

you

, that is

other

. Although you have been busy telling your child that there are other people so that children should be careful and not shit on them, not pee on them, that is something else, actually. That’s used for the sake of convenience. But the others are always there. When children begin to open their eyes, they are aware of others, always there. So we can’t really raise children in a very sneaky Buddhist style [laughter], so that they don’t have any egos left.

Q:

So we only really experience that egolessness through meditation practice . . .

VCTR:

That’s right, that’s the only way. First they have to know what not to have, to have what not to have, in order that they should have what they should have.

Q:

It seems then very obvious that you can’t get rid of ego, because you can’t get rid of something that doesn’t exist.

VCTR:

I beg your pardon?

Q:

You can’t really conquer something that doesn’t exist.

VCTR:

Well, by realizing it doesn’t exist, that

is

conquering, right?

Q:

But in the sense of an aggressive act of conquering.

VCTR:

Well, you can’t destroy it, particularly, but realizing it doesn’t exist as such is at the level of conquering. Because there is so much myth in it, we are more or less destroying the myth, which is regarded as conquering.

Okay, ladies and gentlemen, we could stop this point. I would like to encourage you to take sitting practice more seriously. Since we are getting into much deeper subjects from now onward, it will be very important for you to sit and find out for yourselves what it is all about. Thank you very much.

The Wheel of Life

ILLUSION’S GAME

T

HE WHOLE DHARMA

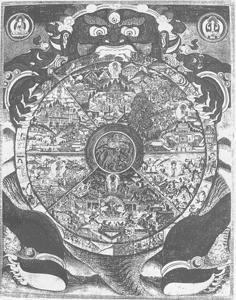

is the language of samsara. That is why this painting is called the wheel of life, or bhavachakra—the wheel of existence, or becoming (samsara). This wheel is the portrait of samsara and therefore also of nirvana, which is the undoing of the samsaric coil. This image provides a good background for understanding illusion’s game, based as it is on the four noble truths as the accurate teaching of being in the world. The outer ring of the nidanas describes the truth of suffering; the inner ring of the six realms describes the impetus of suffering; and the center of the wheel describes the origin of suffering, which is the path.

The wheel of life is always shown as being held by Yama (a personification meaning death, or that which provides the space for birth, death, and survival). Yama is the environment, the time for birth and death. In this case, it is the compulsive nowness in which the universe recurs. It provides the basic medium in which the different stages of the nidanas can be born and die.

The outer ring of the evolutionary stages of suffering is the twelve nidanas.

Nidana

means “chain,” or chain reaction. The nidanas are that which presents the chance to evolve to a crescendo of ignorance or death. The ring of nidanas may be seen in terms of causality or accident from one situation to the next; inescapable coincidence brings a sense of imprisonment and pain, for you have been processed through this gigantic factory as raw material. You do not usually look forward to the outcome, but on the other hand, there is no alternative.

The wheel of life

.

The death of the previous nidana gives birth to the next one within the realm of time, which is itself compulsive. Rather than one ending and another beginning, each nidana contains the quality of the previous one. Within this realm of possibility, the twelve nidanas develop.

The first stage is ignorance, avidya. This is represented by a blind grandmother who symbolizes the older generation giving birth to further situations, but itself remaining fundamentally blind. The grandmother also represents another element, the basic intelligence which is the impetus for stirring up endless clusters of mind/body material, creating such claustrophobia that the crowded situation of the energy sees itself. At this point, the sense of intelligence is undermined—nothing matters but the fundamental deception or loneliness. Simultaneously the overcrowded, clumsy discrimination (thingness, solidified space) is in the way. This is experienced as a subtle irritation combined with subtle absorption. This irritation extends to the grandchild but still remains the grandmother.

This absorption could be called fundamental bewilderment, the “samsaric equivalent of samadhi,” an indulgence in something intangible which is the bewilderment. The solidified space results from trying to confirm this intangible and is the beginning of self-consciousness at that level. You begin to discover that there are possibilities of clinging to intangible qualities as if they were solid. You feel as if there were desolation in the background. You have broken away from something and there’s an urge to create habitual patterns. There is a sense of discovery for you have found some occupation after a whole trip of exploring possibilities, but at the same time you sense the possibility of losing ground forever.