The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (8 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

10

. From

True Command: The Teachings of the Dorje Kasung,

forthcoming from Trident Publications.

11

. Ibid.

12

. Ibid.

13

. Excerpts from this talk were edited into the chapter by that name in

Shambhala

.

14

. Chögyam Trungpa also taught more advanced levels of Shambhala Training, and here too, the atmosphere was unmistakably radiant.

15

. Even today, Level Five is still regarded as the level where a student can first meet Trungpa Rinpoche’s mind. I am grateful to Fabrice Midal for pointing out the importance of Level Five for students today, when he reviewed this manuscript for me.

16

. At this time, I was newly appointed as the editor in chief of Vajradhatu Publications, Previously, I had worked at Shambhala Publications as an in-house editor for about five years. With my training and background as a trade book editor, I was very interested in working on books for the general public when I came to Vajradhatu.

17

. This was co-taught by the Vajra Regent, Ösel Tendzin. Rinpoche would teach one night; the Regent the next. Rinpoche and the Regent taught a number of such seminars, both at Naropa and in various meditation centers around North America.

18

. Additional material for that chapter came from a talk at the Vajradhatu Seminary and from remarks made by Rinpoche during his presentations of Level Five of Shambhala Training.

19

. I had given the manuscript to many senior students of Trungpa Rinpoche’s and had already incorporated their feedback at this point. However, this was someone who was inadvertently overlooked but very motivated to read the manuscript.

20

. Larry Mermelstein pointed out to me that in 1978, the last time that the “Vajra Politics” course was taught, Karl Springer, the instructor and a member of the Board of Directors of Vajradhatu, presented the topic in “a tour-de-force . . . the real beginning of articulating a Shambhala view [of politics].” Larry Mermelstein, note to Carolyn Rose Gimian, December 2002. See also the discussion of Karl Springer’s role in the political development of Vajradhatu, which follows.

21

.

Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly

1, no. 1 (Fall 2002): 57.

22

. One’s primary delek would be located in the town where one lives, but one might also be part of a delek at the Seminary, Kalapa Assembly, or other residential practice and study programs. According to a 1981 article in the

Vajradhatu Sun,

the first time that Rinpoche introduced the delek system was actually at the 1981 Kalapa Assembly.

23

. “Vajracarya Addresses Delegs,”

Vajradhatu Sun

(February/March 1982).

24

. Ibid.

25

.

Vajradhatu Sun

(August/September 1982).

26

. In Tibetan,

dradül

literally means “enemy subduer.”

S

HAMBHALA

The Sacred Path of the Warrior

EDITED BY

C

AROLYN

R

OSE

G

IMIAN

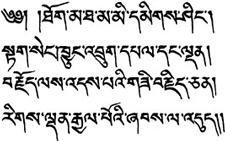

Dawa Sangpo, the first king of Shambhala

.

THANGKA BY NGÖDRUP RONGAE. PHOTOGRAPH BY GEORGE HOLMES.

T

O

G

ESAR OF

L

ING

He who has neither beginning nor end

Who possesses the glory of Tiger Lion Garuda Dragon

Who possesses the confidence beyond words

I pay homage at the feet of the Rigden King

Editor’s Preface

C

HÖGYAM

T

RUNGPA

is best known to Western readers as the author of several popular books on the Buddhist teachings, including

Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, The Myth of Freedom,

and

Meditation in Action

. The present volume,

Shambhala,

is a major departure from these earlier works. Although the author acknowledges the relationship of the Shambhala teachings to Buddhist principles and although he discusses at some length the practice of sitting meditation—which is virtually identical to Buddhist meditation practice—nevertheless, this book presents an unmistakably secular rather than religious outlook. There are barely a half-dozen foreign terms used in the manuscript, and in tone and content this volume speaks directly—sometimes painfully so—to the experience and the challenge of being human.

Even in the name with which he signs the Foreword—Dorje Dradül of Mukpo—the author distinguishes this book from his other works.

Shambhala

is about the path of warriorship, or the path of bravery, that is open to any human being who seeks a genuine and fearless existence. The title

Dorje Dradül

means the “indestructible” or “adamantine warrior.” Mukpo is the author’s family name, which was replaced at an early age by his Buddhist title, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In chapter II, “Nowness,” the author describes the importance that the name Mukpo holds for him and gives us some hints of why he chooses to use it in the context of this book.

Although the author uses the legend and imagery of the Shambhala kingdom as the basis for his presentation, he states quite clearly that he is not presenting the Buddhist

Kalachakra

teachings on Shambhala. Instead, this volume draws on ancient, perhaps even primordial, wisdom and principles of human conduct, as manifested in the traditional, preindustrial societies of Tibet, India, China, Japan, and Korea. In particular, this book draw its imagery and inspiration from the warrior culture of Tibet, which predated Buddhism and remained a basic influence on Tibetan society until the Communist Chinese invasion in 1959. Yet, whatever its sources, the vision that is presented here has not been articulated anywhere else. It is a unique statement on the human condition and potential, which is made more remarkable by its haunting and familiar ring—it is as though we had always known the truths contained here.

The author’s interest in the kingdom of Shambhala dates back to his years in Tibet, where he was the supreme abbot of the Surmang monasteries. As a young man, he studied some of the tantric texts that discuss the legendary kingdom of Shambhala, the path to it, and its inner significance. As he was fleeing from the Communist Chinese over the Himalayas in 1959, Chögyam Trungpa was writing a spiritual account of the history of Shambhala, which unfortunately was lost on the journey. Mr. James George, former Canadian High Commissioner to India and a personal friend of the author, reports that in 1968 Chögyam Trungpa told him that “although he had never been there [Shambhala], he believed in its existence and could see it in his mirror whenever he went into deep meditation.” Mr. George then tells us how he later witnessed the author gazing into a small hand-mirror and describing in detail the kingdom of Shambhala. As Mr. George says: “There was Trungpa in our study describing what he saw as if he were looking out of the window.”

In spite of this longstanding interest in the kingdom of Shambhala, when Chögyam Trungpa first came to the West, he seems to have refrained from any mention of Shambhala, other than passing references. It was only in 1976, a few months before beginning a year’s retreat, that he began to emphasize the importance of the Shambhala teachings. At the 1976 Vajradhatu Seminary, an advanced three-month training course for two hundred students, Chögyam Trungpa gave several talks on the Shambhala principles. Then, during his 1977 retreat, the author began a series of writings on Shambhala, and he requested his students to initiate a secular, public program of meditation, to which he gave the name “Shambhala Training.”

Since that time, the author has given well over a hundred lectures on themes connected with Shambhala vision. Some of these talks have been given to students in the Shambhala Training program, many of them have been addressed to the directors, or teachers, of Shambhala Training, a few of the lectures were given as public talks in major cities in the United States, and one group of talks constituted a public seminar entitled “The Warrior of Shambhala,” taught jointly with Ösel Tendzin at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, in the summer of 1979.

To prepare this volume, the editors, under the author’s guidance, reviewed all of the lectures on the subject matter and searched for the best, or most appropriate, treatments of particular topics. In addition, the author wrote original material for this book, notably the discussion of the dignities of meek, perky, and outrageous that appears in chapter 20, “Authentic Presence.” He had already composed the material on inscrutability as an essay during his 1977 retreat, and the discussion of the other three dignities was written for this book in a style compatible with the original article.

In deciding upon the sequence of chapters and the logical progression of the topics, the original lectures were themselves the foremost guide. In studying this material the editors found that the Shambhala teachings present, not only the logic of the mind, but also the logic of the heart. Based as much on intuition as on intellect, these teachings weave a complex and sometimes crisscrossing picture of human experience. To preserve this character, the editors chose to draw the structure of the book out of the structure of the original lectures themselves. Of necessity, this sometimes resulted in paradoxical or even seemingly contradictory treatments of a topic. Yet we found that the overall elegance and integrity of the material were best served by retaining the inherent logic of the original presentation, with all its complexities.

Respect for the integrity of the original lectures was also the guiding principle in the treatment of language. In his presentation of the Shambhala principles, the author takes common words in the English language, such as “goodness,” and gives them uncommon, often extraordinary, meanings. By doing so, Chögyam Trungpa elevates everyday experience to the level of sacredness, and at the same time, he brings esoteric concepts, such as magic, into the realm of ordinary understanding and perception. This is often done by stretching the English language to accommodate subtle understanding within seeming simplicity. In our editing, we tried to retain and bring out the author’s voice rather than suppress it, feeling that this approach would best convey the power of the material.

Before work on

Shambhala

began, many of the author’s talks had already been edited for use by students and teachers in the Shambhala Training program. These early editorial efforts by Mr. Michael H. Kohn, Mrs. Judith Lief, Mrs. Sarah Levy, Mr. David Rome, Mrs. Barbara Blouin, and Mr. Frank Berliner are gratefully acknowledged; they considerably reduced the task of preparing this book.