The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (16 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The following morning Jamgön Kongtrül asked the monks if they had put his guests in the guest house; surprised, they replied that no one had turned up. The guru insisted that the expected guests had arrived and told them to make further enquiries. The four pilgrims were traced and Trungpa Tulku was recognized. The monks immediately took them to Jamgön Kongtrül and were astonished when the great teacher showed no sign of surprise at the manner in which the party had traveled. After the interview Trungpa Tulku had a long private talk with his guru, who arranged for him to occupy a house with his companions some fifteen minutes’ walk away, where an old monk would see to their wants. Trungpa Tulku immediately settled down to his studies, with his guru instructing him in meditation while the master of studies (

khenpo

) superintended his academic work.

For a year he was left alone, then his secretary and some monks came to see him bringing gifts and money. The secretary had a private talk with Jamgön Kongtrül and asked him to encourage their abbot to return to Surmang on completion of his studies; his guru agreed that he must go back some day, but not immediately, for he and also his attendant monks were making such progress that it would be wrong to disturb them; he added that the elderly bursar could now return to his monastery.

After the visitors had left, Trungpa Tulku gave away all the gifts they had brought, leaving himself and the two monks with hardly anything to eat, so that they were obliged to go round with their begging bowls. The two monks were naturally very upset over this, for while the bursar had been with them there had always been enough for their requirements and they could not understand this new phase. Trungpa Tulku, however, insisted that austerity was the right course and the only way to follow the Buddha’s example, as well as that of Milarepa. They must therefore beg until they had received the bare necessities of food to last out the winter. Moreover they had very little butter for their lamps; incense however was cheap and when blown upon produced a faint glow by which Trungpa Rinpoche was able to light up a few lines at a time of the book he was studying.

Now that the monks of Palpung and the people in the district knew of Trungpa Tulku’s presence, they kept coming to visit him which he found very disturbing to his meditations.

After three years Surmang expected their abbot to return, and again sent a party of monks to fetch him. This time Düldzin, the senior secretary’s nephew, came with them. They found the two monks who were with Trungpa Tulku very disturbed in mind; the austere way of living that had been imposed upon them was affecting their health. However, Trungpa wished to stay on at Palpung until his studies were completed, so it was decided that they should return to Surmang with the party and that Düldzin, at his own request, should remain to look after Trungpa. However, this arrangement did not prove altogether a success, for he gave Trungpa Tulku a lot of trouble. The two men had very different approaches to life: The abbot was a strict vegetarian and wanted everything to be as simple as possible, whereas Düldzin expected to have meat and disliked such plain living. Later Trungpa Tulku realized that these difficulties had been a lesson to him and that lamas had often to experience this sort of trouble and must learn to control their own impatience and accept the fact that their attendants could not be expected to live at their own high level of austerity.

At the end of a further three years, Jamgön Kongtrül considered that Trungpa Rinpoche had made such progress that he could be trusted to act as a teacher himself and to carry on the message of dharma to others. Trungpa, for his part, felt that if he was to carry on this work he required still more experience; he should travel to seek further instruction, as his guru had done, and live a life given up to meditation. However, Jamgön Kongtrül pointed out that he must compromise between taking such a path and his monasteries’ need for him to return to them. He said, “It must be according to your destiny; conformably with the will of your past nine incarnations your duty lies in governing your monasteries. This is your work and you must return to it. If you take full charge you can rule them in the way you feel to be right. You must establish five meditation centers, the first in your own monastery and the other four in neighboring ones. This will be a beginning; in this way your teaching will not confined to your own monks, but you will be able to spread it more widely.”

Trungpa Tulku followed his guru’s directions; the parting was a sad moment for them both, and after a farewell party he began his return journey on foot. Back at Surmang, he immediately set to work to establish a meditation center and to put the affairs of his monasteries in order. While he was thus engaged news came that Jamgön Kongtrül had died; however, in spite of this deep sorrow he carried on with his work of establishing the four other meditation centers, all of which continued to flourish until the Communists took possession of Tibet in my lifetime.

As Jamgön Kongtrül’s entrusted successor, the tenth Trungpa Tulku later became the guru of both Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen and Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung. At Surmang, he gained more and more followers and such was the example of the simplicity of his life that he was regarded as a second Milarepa.

When he was about fifty years old there was a border dispute between the Chinese and Tibetan governments and in the course of the fighting much damage was done to both Namgyal Tse and Dütsi Tel. Trungpa Tulku himself was taken prisoner; worn out by forced marches on an empty stomach and already weakened by his austere vegetarian diet, he became ill. His devotee, the king of Lhathok, succeeded in obtaining his release and managed to persuade him to take better care of himself by traveling sometimes on horseback instead of always going on foot. When he returned to Surmang there was much work ahead for him; the monasteries had to be rebuilt and at the same time he had to continue his teaching. In spite of the fact that he was growing old and was in poor health he only allowed himself three to four hours for sleep and gave his strength unstintingly to the work of rebuilding the monasteries. He always maintained that if one followed the true path financial help would be given when it was really needed. He accepted the destruction of the monasteries as a lesson in nonattachment which had always held a foremost place in the Buddha’s teaching. The lamas considered that their supreme abbot’s residence should be furnished with every comfort, but he himself insisted on complete simplicity.

Soon, Trungpa Tulku realized that he was approaching the end of his life. One day he had a dream that he was a young child and that his mother was wearing the style of headdress peculiar to northeastern Tibet. When a new robe was being made for him he told his secretary that it should be a small one; on the secretary asking why, he turned it away as a joke. Trungpa used to say that he felt sorry for his horse, for soon he would no longer be able to walk and would cause it more trouble; the secretary was disturbed at this remark, for he thought that this meant that his abbot was really losing his health.

In 1938 while on tour Trungpa suddenly said that he must get back to his monastery; however, he found it impossible to change his plans as he had received so many invitations from various devotees. When one of the king of Lhathok’s ministers asked him to visit him, he accepted, though this meant a long journey; the lama added that he might have to ask him to be one of the most important hosts of his lifetime. He arrived on the day of the full moon in a very happy mood, but did what was for him an unusual thing; on arriving at the house he took off his socks and his overrobe and, turning to his monks, told them to prepare for a very special rite. A meal was served, but he did not feel inclined to eat and having said grace, he told them to put the food before the shrine. Then he lay down saying, “This is the end of action.” These were his last words: Lifting himself up he took the meditation posture, closed his eyes, and entered samadhi.

His monks thought he was in a coma, and one doctor among them examined him, drawing some of his blood and burning herbs to revive him, but with no result. The monks stood by him all the time reciting sutras and mantras; he looked as if he was still alive and remained in the same meditation posture until midnight when there was a flash of light and the body fell over.

The eye of gnosis

.

I Go to My Guru

I

LEFT

D

ORJE

K

HYUNG

D

ZONG

with my predecessor’s story uppermost in my mind. I knew I must now discuss future plans with my secretary and bursar. When I brought the matter forward, they gave me my choice, but said that traditionally the tour round the district should be carried out; however, I had the right to do as I wished, so again I was thrown back on myself. It was much easier for me to talk to my tutor; I explained to him that what I really wanted to do was to receive further teaching under Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen. I wanted to make a complete break from the studies I had hitherto followed and to do something quite different; I added, once one sets out on a tour there are continual invitations from all sides, which protract it indefinitely; but since the monastic committee had been so kind and had given me such wonderful opportunities for studying, I would not like to say no to them.

At this time, I received two invitations, one from the distant monastery of Drölma Lhakhang, in Chamdo province, the other from the king of Lhathok; this latter would in any case be included in the traditional tour. My lamas were delighted at this chance of encouraging me to travel and make wider contacts. The representative from Drölma Lhakhang was worrying lest I should not agree to go, for the whole district wanted to see their abbot and the disappointment would be very great if this visit was refused. This made it very difficult for me, for if I accepted, I would also have to go on a lengthy tour, and if I did not go, these people would be upset. My own wish was to proceed straight to my guru; the only thing to do was to tell the monastic committee plainly that I must be free to go to Sechen before the end of the year. I said that I was very anxious not to go against their wishes, so we would have to make a compromise; finally it was arranged that the tour should take place, including a visit to the principality of Lhathok, for this was not so far away. I would not, however, visit Drölma Lhakhang; a disciple of the tenth Trungpa Tulku would have to go instead. Before setting out I asked my secretary to promise that on my return I could go to Sechen; he should also make all arrangements at Surmang for my intended absence.

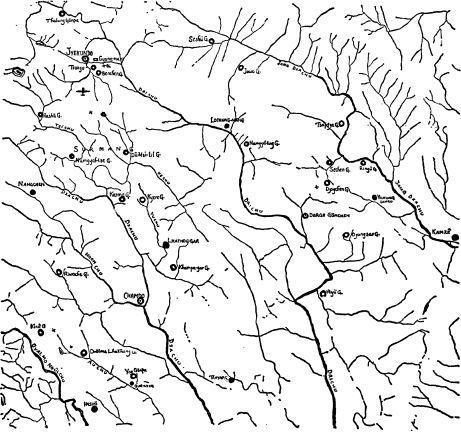

Map of Surmang area of Tibet

.

Our traveling party was organized with a good deal of pomp. There were thirty monks on horseback and eighty mules to carry the baggage. I was still only twelve and, being so young, I was not expected to preach long sermons; mostly I had to perform rites, read the scriptures aloud, and impart blessings. We started from the highlands and traveled down to the cultivated land; I was able to see how all these different people lived as we passed through many changes of scenery. Of course I did not see the villagers quite as they were in their everyday lives, for wherever we went all was in festival; everyone was excited and looking forward to the special religious services, so that we had little time for rest. I missed the routine of my early life, but found it all very exciting.

When we visited Lhathok, the king had to follow the established tradition by asking us to perform the religious rites according to ancient custom. We were lodged in one of the palaces, from where we could look down on a school that the Chinese had recently established. A Communist flag hung at the gate, and when it was lowered in the evenings the children had to sing the Communist national anthem. Lessons were given in both Chinese and Tibetan, including much indoctrination about the benefits China was bringing to Tibet. Singing and dancing were encouraged and I felt that it was a sign of the times that the monastery drum was used to teach the children to march. Being young myself I was keenly interested, though this distortion worried me; a religious instrument should not have been used for a secular purpose, nor for mere amusement. A detachment of Chinese officials sent from their main headquarters at Chamdo lived in the king’s palace together with a Tibetan interpreter, while various teachers had been brought to Lhathok to organize the school, which was one of many that the Chinese were setting up in all the chief places in Tibet. The local people’s reactions were very unfavorable. In the town the Communists had stuck posters or painted slogans everywhere, even on the walls of the monastery; they consisted of phrases like “We come to help you” and “The liberation army is always at the people’s service.”