The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (26 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Since the abbot was still a child, Khenpo Gangshar had a talk with the regent who was very interested in his teaching on nonviolence as it agreed with his own scholarly point of view. He took us round the monastery, and showed us the Buddha image which had been given to Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Geluk school, on his ordination; this had been made quite small so that he could always carry it with him. It had been preserved at Seshü and treated with the greatest veneration; one felt an atmosphere of holiness surrounding it. The assembly hall held three thousand monks sitting very close together, and the noise of the chanting from so great a number was tremendous. In the Geluk monasteries the study of logic plays an important part; after listening to lectures the monks congregate in the courtyard where they form debating groups according to the ages of the participants which can be from eight years upward; we were able to observe this method. When a monk put his question to another in the group, he stood up, stamped his foot, and clapped his hands to mark his points. When he succeeded, he swung his rosary from arm to arm, if defeated he swung it over his head. The monk questioned would return the attack sitting down. So the courtyard was extremely noisy and lively.

Unfortunately we could not stay for long at Seshü, and we resumed our journey in very cold weather, for the district lay at a high altitude; its farming highlanders live in tents.

When we were a day’s journey from Sechen we were told that after all the monastery had not been badly damaged and that some of the lamas were then visiting a monastery close to our route. We sent them a message and they came to meet us at Phu-khung. They told us how the Communists had shut them up in one of the shrine rooms handcuffed in such a way that they were unable to move and had given them hardly anything to eat or drink. The Communists had made a thorough search, but found nothing, and after angry expostulations from the villagers they had released the lamas and left the monastery. The monks were allowed to stay on, though the Chinese camped all around, and the lamas had to get permission from them every time they went outside the immediate area. Other neighboring monasteries had been completely destroyed, and the lamas were very upset by this. They did not want to leave Sechen, but feared what might still happen. They discussed all this with Khenpo Gangshar. He told them that conditions were unlikely to improve and that he could hold out little hope of his being able to persuade the Chinese to accept the Buddha’s teaching of nonviolence. He was afraid there would be no safety in any part of Tibet, but did not know how a whole group of monks could keep together anywhere outside.

Gangshar now advised me to go back to Surmang to continue our common work, but since his pleas with the Chinese officials had not seemed very successful, I was afraid that it would be dangerous for him to remain in Derge. We had only three more days together, during which he gave me his last teachings on meditation and some other general instructions; then I had to leave. I had had to part from my guru Jamgön Kongtrül and now my last support, the guru to whom he had passed me on, was to be taken from me. I was alone.

When my monks and I returned to Surmang we found everything apparently going well at the seminary and everyone was anxious to hear what Khenpo Gangshar had been able to accomplish. During my absence the Communists had summoned my secretary to a conference. They told him that our monastery must pay fifty thousand Chinese silver dollars in taxes and that all Indian and European goods must be handed over to them and no further one obtained; these included such things as wristwatches and also any photographs of the Dalai Lama which had been taken in India. They also said that in future I must attend the conferences in person.

It was now the end of 1958. We held our annual twelve-day devotional celebration to dispel past evils and to bring us new spiritual life in the forthcoming year. It was a joyous time and I did not mind the hard work which this entailed.

I had often spent the New Year festival very quietly at our retreat center and this year I did the same. I found the lamas there a little disturbed by the fact that they had broken their vows of remaining in seclusion as Khenpo Gangshar had enjoined. However they seemed to have advanced spiritually both through their contact with the khenpo and other people. I explained to them that going out of their center was not really against their vows, but part of their training, which had great meaning.

Returning to the monastery after the New Year, I spent several days discussing the situation with Rölpa Dorje Rinpoche, my regent abbot of Dütsi Tel. He seemed suddenly this year to have grown much older, and was very thoughtful. He said to me, “It seems that the Chinese are becoming more and more aggressive, and I know how brutal the Russian Communists were in Mongolia, destroying all the monasteries. Perhaps an old man like myself could escape through death; my health is no longer good, but I feel very anxious for the younger generation. If you can save yourselves, and I am thinking especially of you, the eleventh Trungpa Tulku who have received so much instruction and training, it would be worthwhile. For myself, I feel I should not leave the monastery without consulting Gyalwa Karmapa as the head of our whole monastic confraternity. As the Chinese attitude toward His Holiness the Dalai Lama and its government is still respectful, we have not lost hope that he will be able to restore order and protect the dharma.”

Image of Milarepa that belonged to Gampopa. A Surmang treasure

.

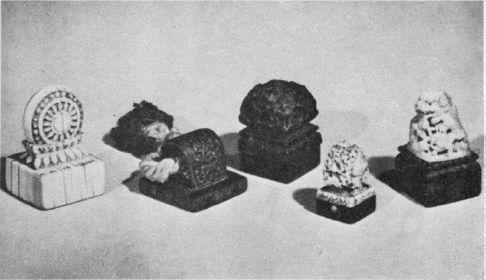

The seals of the Trungpa Tulkus. The large ivory seal was offered to the fifth Trungpa by the emperor of China

.

Headdress of a Khampa woman

.

PHOTO: PAUL POPPER, LTD.

A Khampa nomad peasant

.

PHOTO: PAUL POPPER, LTD.

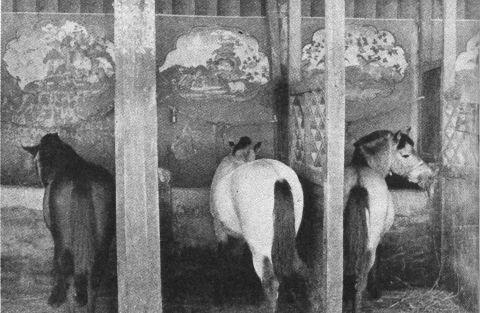

The Dalai Lama’s stables at Lhasa

.

PHOTO: PAUL POPPER, LTD.

I was now nineteen according to the European solar calendar, but by the Tibetan which dates from birth by the number of lunar months, I was considered to be twenty. Though I had been given the degree of khenpo, I still needed to be fully ordained as a bhikshu. Since I was now old enough I was able to request my regent abbot and four other bhikshus to ordain me; as I had already studied the canon of monastic discipline (Vinaya) they agreed that the ordination could take place. I was given the begging bowl which had belonged to the tenth Trungpa Tulku and the yellow robe of a bhikshu. I had to take 250 vows, some of which I had already made as a novice (shramanera). My ordination took place at the altar in front of the image of the Buddha. This qualified me to conduct the rite of Sojong to restore virtue and bring purification from wrongdoing which takes place on full moon and new moon days; but above all I felt a sense of maturity as a fully prepared member of the sangha.

Rölpa Dorje Rinpoche now left on a tour to visit his devotees in and around Jyekundo and I took charge of the seminary as its khenpo. I still felt inexperienced beside Khenpo Sangden and the kyorpöns who had spent many more years than I at their studies. However, my secretary and the older disciples of my predecessor were satisfied, and I felt that I was following in the tenth Trungpa Tulku’s footsteps. As I sat on Khenpo Gangshar’s throne, I had a deep sense of all he had given us; more and more I felt the need of his presence and of a wider knowledge of the dharma. The needs of the local people often required my presence to give teaching or to help the sick and the dying. As this meant leaving the monastery at all hours nearly every day, I realized that I must have an assistant khenpo who could give more individual attention to the students, and we agreed to ask Khenpo Sangden to fill this post; he also took over much of the lecturing. We were now studying

The Ornament of Precious Liberation

(

Tharpa Rinpoche Gyen

) by Chöje Gampopa.

1

The sister of the tenth Trungpa Tulku, who had looked after the dairy at Dütsi Tel had died, and my mother now took charge. This made her very happy as she loved animals, but it also involved looking after the herdsmen and arranging about their wages. After a time she found this too much for her and gradually handed over the work to an assistant. When I was living in my own residence outside the monastery she was able to stay with me and do my cooking. This was a great happiness for both of us.

In the spring I received an invitation from the neighboring province of Chamdo, some three days’ journey from Surmang, to come and lecture, for many of the people there were anxious to hear more of Khenpo Gangshar Rinpoche’s teachings. After a week there, a messenger came from our monastery to tell me that Rölpa Dorje was ill; immediately afterward a second messenger arrived to say that he was dying. I at once returned to Dütsi Tel, traveling day and night without stopping. My monks were waiting for me and some forty of us went together to the place where we now knew he had died.