Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (47 page)

With the invitation from Boulder and the news of the establishment of Tail of the Tiger, added to the growing inhospitableness of our situation in Scotland, Diana and I departed for America. My physical disability and her youth made the journey, and what lay ahead of us, all the more exciting. On the airplane from Glasgow to Toronto, we talked of conquering the American continent, and we were filled with a kind of constant humor. As we did not yet have a visa to enter the United States, we proceeded to Montreal, where we spent the next six weeks living in a small apartment. Students from Tail of the Tiger came up to visit, and I also responded to several requests to teach in Montreal. In May of 1970, we obtained our visa and entered the United States.

At Tail of the Tiger we found an undisciplined atmosphere combining the flavors of New York City and hippies. Here too people still seemed to miss the point of dharma, though not in the same way as in Britain, but in American free-thinking style. Everyone was eager to jump into tantric practices at once. Traveling to California on a teaching tour set up by Tail of the Tiger and Mr. Bercholz, I encountered many more free-style people indulging themselves in confused spiritual pursuits. The saving grace of this visit was the warm hospitality offered me by Mr. Bercholz and his colleagues in Shambhala Publications, which was located in Berkeley. At the same time, I realized that the energy behind people’s fascinations was beginning to lighten and that America held genuine possibilities for receiving the dharma. Meeting the students of other teachers was especially disappointing. These students seemed to lack any understanding of discipline, and purely to appreciate teachers who went along with their own neurosis. No one seemed to be presenting a way of cutting through the students’ neurosis. One outstanding exception to this situation was Shunryu Suzuki Roshi and his students, whose presence felt like a breath of fresh air. I would have more contact with them later.

Vidyadhara the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, February 1977

.

PHOTO: ANDREA CRAIG.

Vajra Regent Ösel Tendzin

.

PHOTO: BLAIR HANSEN.

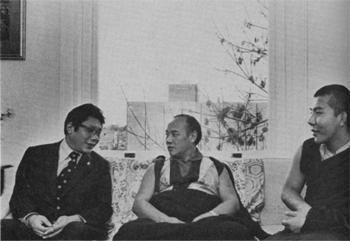

Left to right:

Trungpa Rinpoche, His Holiness the sixteenth Gyalwa Karmapa, and Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung

.

PHOTO: JAMES GRITZ.

Diana Mukpo riding dressage

.

I returned to Tail of the Tiger where I presented my first long seminar in this country, consisting of seventeen talks on Gampopa’s text

The Jewel Ornament of Liberation

. This was followed by a similar seminar on the life and teachings of Milarepa. During this period Diana returned to England to try and fetch my eight-year-old Tibetan son, Ösel Rangdröl tülku, who had remained behind in the care of Christopher Woodman. To our surprise, Mr. Woodman refused to let him go, deciding to hold him as a captive. A court case followed which resulted in Ösel being temporarily sent to live at the Pestalozzi Children’s Village in Sussex. Here I visited him for ten days in the autumn of 1970. It was not until the following year that we were able to bring Ösel to live with us in America.

From England, I flew directly to Denver, Colorado, where I was received by the University of Colorado group. They provided initial hospitality, putting me up in a cabin in Gold Hill, an old mining town in the mountains above Boulder. After a few weeks, I moved to a larger house in Four Mile Canyon near Boulder, where Diana joined me. Both of us took a strong liking to the city of Boulder, its fresh air, its manageable size, and of course its mountains. I began to teach and a community of students began to gather, renting a house on Alpine Street to which I gave the name Anitya Bhavan, “House of Impermanence.” Gradually the feeling of the students was changing and I saw definite potential for transforming them from homegrown dilettantes into genuine disciplined people.

As the enthusiasm for meditation practice and study grew, so did our membership. A group of students of Swami Satchidananda’s Integral Yoga Institute first hosted us, then joined us, and we took over their practice facilities on Pearl Street in downtown Boulder. One California disciple of Swami Satchidananda, a young American of Italian background, came to me with an invitation to attend a World Enlightenment Festival. He was known as Narayana, a colorful personality with lots of smiles, possessing the charm of American Hindu diplomacy. From the first, I felt some definite sense of connection with him.

In March of 1971 Diana gave birth to a son. Witnessing the birth, I was filled with a sense of delight and of the child’s sacredness. His Holiness the Dalai Lama gave him the name of Tendzin Lhawang, and I added Taktruk, meaning “tiger’s cub.” Later he was recognized by His Holiness Karmapa as the rebirth of one of his teachers, Surmang Tendzin Rinpoche.

The energy and openness of the students now began to unfold quite rapidly, and we formally established a meditation center in Boulder under the name of Karma Dzong, “Fortress of Action.” In addition, after a certain amount of searching, we purchased 360 acres of land west of Fort Collins, Colorado, which we called the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center. The first students who moved on to this land were a group of young and quite innocent hippies who called themselves “The Pygmies.”

During this period I traveled a great deal. On my second visit to California, I was able to spend more time with Suzuki Roshi, and this proved to be an extraordinary and very special experience. Suzuki Roshi was a Zen master in the Soto Zen tradition who had come to America in 1958 and founded the Zen Center, San Francisco, and Zen Mountain Center at Tassajara Springs. He was a man of genuine Buddhism, delightful and profound, full of flashes of Zen wit. In the example of his spiritual power and integrity, I found great encouragement that genuine Buddhism could be established in America. His students were disciplined and dedicated to the practice of meditation, and on the whole presented themselves as precise and tidy. Mrs. Suzuki also I found to be a wonderful woman who was very generous to both myself and Diana.

When Suzuki Roshi died in December of 1971, I was left with a feeling of great lonesomeness. Yet his death had the effect on me of arousing further strength; his genuine effort to plant the dharma in America must not be allowed to die. I did, however, feel especially keenly the loss of the possibility of exploring further the link between Tibetan and Japanese culture. Since coming to the West, I have become increasingly fascinated with aesthetics and the psychology of beauty. Through Suzuki Roshi’s spiritual strength and his accomplishments in the arts of the Zen tradition, I felt I could have learned much more in these areas.

During this period my presentation of the dharma to students was based on the practice of pure sitting meditation, the traditional shamatha-vipashyana technique presented by the Buddha. Students maintained a daily sitting practice, as well as taking intensive solitary and group meditation retreats. The other major element in my teaching was continual warnings against dilettantism, spiritual shopping, and the dangers of spiritual materialism. The enthusiasm and trust of students all over America continued to accelerate, with the result that local centers for study and practice sprang up in different parts of the United States and Canada. To all of these centers we gave the name Dharmadhatu, meaning “Space of Dharma.” Now, inspired by the strength of my encounter with Suzuki Roshi and by the genuine friendship of my own students, I decided to establish Vajradhatu, a national organization with offices in Boulder to oversee and unify the present and future Dharmadhatus. Narayana became an early member of Vajradhatu’s board of directors.

Alongside the traditional teachings and practice of Buddhism, one of my principal intents was to develop a Buddhist culture, one which would transcend the cultural characteristics of particular nationalities. An early step in this direction was the establishment of the Mudra theater group. It developed out of a notorious theater conference which we hosted in Boulder early in 1973 bringing together our students and members of various experimental theater groups from around the country such as the Open Theater, the Byrd-Hoffmann, and the Provisional Theater. Amid the variety of demonstrations and exchanges taking place among the participants, my personal style and uncompromisingness had both positive and negative effects; in any case, all of the participants became highly energized. Following this conference, I presented to our own Mudra theater group the notion of training body, speech, and mind rather than immediately embarking on conventional performances. I introduced a series of exercises based on Tibetan monastic dance and the oriental martial arts which focused on the principles of center and space and their mutual intensification and diffusion. Members of the Mudra group have maintained a regular practice over the years and are now at the point of presenting performances to the public, which they have begun with two short plays of my own composition.

The Mudra approach to theater has a parallel in the Maitri project, which also got under way at this time. The idea for it arose from a discussion that Suzuki Roshi and I had had concerning the need for a therapeutic facility for disturbed individuals interested in meditation. The Maitri approach to therapy involves working the different styles of neurosis through the tantric principles of the five buddha families. Rather than being subjected to any form of analysis, individuals are encouraged to encounter their own energies through a meditation practice employing various postures in rooms of corresponding shapes and colors. A major facility for these practices, the Maitri Center, is located on a secluded, ninety-acre farm outside of New York City.

In May of 1973 my third son, Gesar Arthur, was born. We named him after the two great warrior kings, of ancient Tibet and England. Later he was recognized by Khyentse Rinpoche and His Holiness Karmapa as the rebirth of my own root guru, Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen.

As students became more completely involved with practice and study, I felt there was a need for more advanced training in the tradition of Jamgön Kongtrül the Great and of the Kagyü contemplative order. A situation was needed in which a systematic and thorough presentation of the dharma could be made. Accordingly, I initiated the annual Vajradhatu Seminary, a three-month intensive practice and study retreat for mature students. The first of these seminaries, involving eighty students, took place at Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in the autumn of 1973. Periods of all-day sitting meditation alternated with a study program methodically progressing through the three yanas of Buddhist teaching, hinayana, mahayana, and vajrayana.