The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (59 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

If you can be as open as that, then you will learn something without fail—this can be guaranteed, not because I am such an authority to say so, but because it is a fact. This has been tested over thousands of years; it has been proved and practiced by all the great adepts of the past. It is not something which has been achieved only by Buddha himself, but there is a long tradition of examining, studying, and testing by many great teachers, like the long process of purifying gold by beating and hammering and melting it down. Still, it is not enough to accept this on anyone’s authority. One must go into it and see it for oneself. So the only thing to do is to put it into effect and start meditating on the subject of prajna, which is very important here, for prajna alone can deliver us from self-centeredness, from ego. Teachings without prajna would still bind us, as they would merely add to the world of samsara, the world of confusion. One may even practice meditation or read scriptures or attend ceremonies, but without prajna there would be no liberation, without prajna one would be unable to see the situation clearly. That is to say that without prajna one would start from the wrong point, one would start by thinking, “I would like to achieve such-and-such, and once I have learned, how happy I will be!” At this stage prajna is

critical insight

, which is the opposite of ignorance, of ignoring one’s true nature. Ignorance is often represented symbolically as a pig, because the pig never turns his head but just snuffles on and on and eats whatever comes in front of him. So it is prajna which enables us not merely to consume whatever is put in front of us, but to see it with critical insight.

Finally we come to gompa, meditation. First we had theory, then contemplation, and now meditation in the sense of samadhi. The first stage of gompa is to ask oneself, “Who am I?” Though this is not really a question. In fact it is a statement, because “Who am I?” contains the answer. The thing is not to start from “I” and then want to achieve something, but to start directly with the subject. In other words one starts the real meditation without aiming for anything, without the thought, “I want to achieve.” Since one does not know “Who am I?” one would not start from “I” at all, and one even begins to learn from beyond that point. What remains is simply to start on the subject, to start on what

is

, which is not really “I am.” So one goes directly to that, directly to the “is.” This may sound a bit vague and mysterious, because these terms have been used so much and by so many people; we must try then to clarify this by relating it to ourselves. The first point is not to think in terms of “I,” “I want to achieve.” Since there is no one to do the achieving, and we haven’t even grasped that yet, we should not try to prepare anything at all for the future.

There is a story in Tibet about a thief who was a great fool. He stole a large sack of barley one day and was very pleased with himself. He hung it up over his bed, suspended from the ceiling, because he thought it would be safest there from the rats and other animals. But one rat was very cunning and found a way to get to it. Meanwhile the thief was thinking, “Now, I’ll sell this barley to somebody, perhaps my next-door neighbor, and get some silver coins for it. Then I could buy something else and then sell that at a profit. If I go on like this I’ll soon be very rich, then I can get married and have a proper home. After that I could have a son. Yes, I shall have a son! Now what name shall I give him?” At that moment the moon had just risen and he saw the moonlight shining in through the window onto his bed. So he thought, “Ah, I shall call him Dawa” (which is the Tibetan word for moon). And at that very moment the rat had finished eating right through the rope from which the bag was hanging, and the bag dropped on the thief and killed him.

Similarly, since we haven’t got a son and we don’t even know “Who am I?” we should not explore the details of such fantasies. We should not start off by expecting any kind of reward. There should be no striving and no trying to achieve anything. One might then feel, “Since there is no fixed purpose and there is nothing to attain, wouldn’t it be rather boring? Isn’t it rather like just being nowhere?” Well, that is the whole point. Generally we do things because we want to achieve something; we never do anything without first thinking, “Because . . .” “I’m going for a holiday

because

I want to relax, I want a rest.” “I am going to do such-and-such

because

I think it would be interesting.” So every action, every step we take, is conditioned by ego. It is conditioned by the illusory concept of “I,” which has not even been questioned. Everything is built around that and everything begins with “because.” So that is the whole point. Meditating without any purpose may sound boring, but the fact is we haven’t sufficient courage to go into it and just give it a try. Somehow we have to be courageous. Since one is interested and one wants to go further, the best thing would be to do it perfectly and not start with too many subjects, but start with one subject and really go into it thoroughly. It may not sound interesting, it may not be exciting all the time, but excitement is not the only thing to be gained, and one must also develop patience. One must be willing to take a chance and in that sense make use of willpower.

One has to go forward without fear of the unknown, and if one does go a little bit further, one finds it is possible to start without thinking “because,” without thinking “I will achieve something,” without just living in the future. One must not build fantasies around the future and just use that as one’s impetus and source of encouragement, but one should try to get the real feeling of the present moment. That is to say that meditation can only be put into effect if it is not conditioned by any of our normal ways of dealing with situations. One must practice meditation directly without expectation or judgment and without thinking in terms of the future at all. Just leap into it. Jump into it without looking back. Just start on the technique without a second thought. Techniques, of course, vary a great deal, as everything depends on the person’s character. Therefore no generalized technique can be suggested.

Well, those are the methods by which wisdom, sherab, can be developed. Now, wisdom sees so far and so deep, it sees before the past and after the future. In other words wisdom starts without making any mistakes, because it sees the situation so clearly. So for the first time we must begin to deal with situations without making the blind mistake of starting from “I”—which doesn’t even exist. And having taken that first step, we will find deeper insight and make fresh discoveries, because for the first time we will see a kind of new dimension: We will see that one can in fact be at the end result at the same time that one is traveling along the path. This can only happen when there is no “I” to start with, when there is no expectation. The whole practice of meditation is based on this ground. And here you can see quite clearly that meditation is not trying to escape from life, it is not trying to reach a utopian state of mind, nor is it a question of mental gymnastics. Meditation is just trying to see what

is

, and there is nothing mysterious about it. Therefore one has to simplify everything right down to the immediate present practice of what one is doing, without expectations, without judgments, and without opinions. Nor should one have any concept of being involved in a battle against “evil” or of fighting on the side of “good.” At the same time one should not think in terms of being limited, in the sense of not being allowed to have thoughts or even think of “I,” because that would be confining oneself in such a small space that it would amount to an extreme form of shila, or discipline. Basically there are two stages in the practice of meditation. The first involves disciplining oneself to develop the first starting point of meditation, and here certain techniques, such as observing the breathing, are used. At the second stage one surpasses and sees the reality behind the technique of breathing, or whatever the technique may be, and one develops an approach to actual reality through the technique, a kind of feeling of becoming one with the present moment.

This may sound a little bit vague. But I think it is better to leave it that way, because as far as the details of meditation are concerned I don’t think it helps to generalize. Since the techniques depend on the need of the person, they can only be discussed individually; one cannot conduct a class on meditation practice.

M

UDRA

Early Poems and Songs

The publishers wish to express their sincere thanks to the following for permission to quote from various works: Herbert V. Guenther,

The Life and Teaching of Naropa

(Oxford University Press); and Charles Tuttle & Co.,

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

, by Paul Reps (for use of the Oxherding illustrations by Tomikichiro Tokuriki).

T

O MY GURU

J

AMGÖN

K

ONGTRÜL

R

INPOCHE

Homage to the Guru of Inner Awareness

The body of the dharma is in itself peace,

And therefore it has never emerged from itself;

And yet light is kindled in the womb,

And from the womb and within the womb the play of blessings arise;

That is to say, the energy of compassion begins its ceaseless operation.

One who follows the Buddha, dharma, and sangha is aware of emptiness; that knowledge of emptiness and of loving-kindness which is without self is called the great perfection of equanimity, by means of which one has sight of this very world as the mandala of all the buddhas.

May this guide you and be your companion in your pilgrimage to liberation; led by the light of wisdom, may you attain to the form of the Great Compassionate One.

I

T IS A GREAT PLEASURE

that I can share some of my experiences with the world. The situation presents itself with publishing a small book called

Mudra

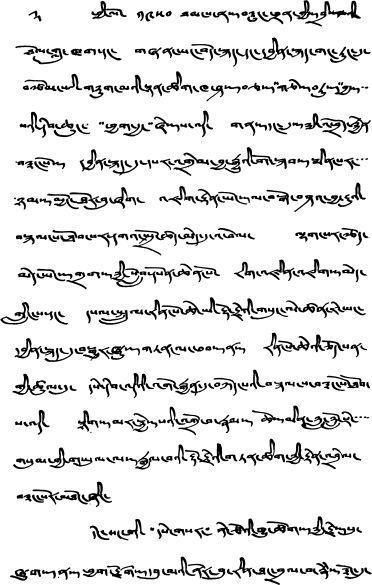

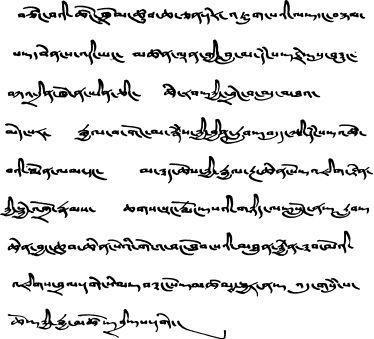

which is a selection of some of my songs and other spontaneous poems which I wrote since 1959 in Tibetan and English. I feel particularly blessed that I was able to include some works of authentic teachers: Jigme Lingpa and Paltrül Rinpoche, which I have translated into English. As the crown jewel, this book carries these translations at its beginning. They are the vajra statement which frees the people of the dark ages from the three lords of materialism and their warfare.

It is the great blessing of the victorious lineage which has saved me from the modern parrot flock who parley such precious jewels like mahamudra, maha ati, and madhyamika teachings on the busy marketplace.

May I continuously gain health throughout my lives from the elixir of life which is the blessing of this lineage.