The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (48 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

And then we come to the vajrayana type of devotion in which you have given up fascination. You have identified with the path and the phenomenal world becomes an expression of the guru. There is a sense of devotion to the phenomenal world. You finally identify with the teachings and occasionally you act as a spokesman for them. Even to your own subconscious mind you act as their spokesman. If we are able to reach this level, then any events which occur in life have messages in them, have teachings in them. Teachings are everywhere. This is not a simple-minded notion of magic in the sense of gadgetry or trickery, but it is an astounding situation which you could interpret as magic. There is cause and effect involved. The events of your life act as a spokesman constantly and you cannot get away from this guru; in fact you do not want to because you identify with it. Thus the teachings become less claustrophobic, which enables you to discover the magical quality of life situations as a teaching.

Generally, devotion is regarded as coming from the heart rather than the head. But tantric devotion involves the head as well as the heart. For instance, the

Tibetan Book of the Dead

uses the symbolism of the peaceful deities coming out of your heart and the wrathful deities coming from your head. The vajrayana approach is a head approach—head plus heart together. The hinayana and mahayana approaches to devotion come from the heart. The tantric approach to life is intellectual in some sense because you begin to read the implications behind things. You begin to see messages that wake you up. But at the same time that intellect is not based upon speculation but is felt wholeheartedly, with one-hundred-percent heart. So we could say that the tantric approach to the messages of the all-pervading guru is to begin with intellect, which is transmuted into vajra intellect, and that begins to ignite the intuition of the heart at the same time.

This is the ideal fundamental union of prajna and shunyata, the union of eyes and heart together. Everyday events become self-existing teachings. Even the notion of trust does not apply any more. You might ask, “Who is doing this trusting?” Nobody! Trust itself is trusting itself. The mandala of self-existing energy does not have to be maintained by anything at all; it maintains itself. Space does not have a fringe or a center. Each corner of space is center as well as fringe. That is the all-pervading devotion in which the devotee is not separate from the object of devotion.

But before we indulge too much in such exciting and mystical language, we have to start very simply by giving, opening, displaying our ego, making a gift of our ego to our spiritual friend. If we are unable to do this, then the path never begins because there is nobody to walk on it. The teaching exists but the practitioner must acknowledge the teaching, must embody it.

EIGHT

Tantra

A

LONENESS

T

HE SPIRITUAL PATH

is not fun—better not begin it. If you must begin, then go all the way, because if you begin and quit, the unfinished business you have left behind begins to haunt you all the time. The path, as Suzuki Roshi mentions in

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind,

is like getting on to a train that you cannot get off; you ride it on and on and on. The mahayana scriptures compare the bodhisattva vow of acceptance of the path to planting a tree. So stepping on the path involves you in continual growth, which may be tremendously painful since you sometimes try to step off the path. You do not really want to get into it fully; it is too close to the heart. And you are not able to trust in the heart. Your experiences become too penetrating, too naked, too obvious. Then you try to escape, but your avoidance creates pain which in turn inspires you to continue on the path. So your setbacks and suffering are part of the creative process of the path.

The continuity of the path is expressed in the ideas of ground tantra, path tantra, and fruition tantra. Ground tantra is acknowledging the potential that exists within you, that you are part of buddha nature, otherwise you would not be able to appreciate the teachings. And it acknowledges your starting point, your confusion and pain. Your suffering is truth; it is intelligent. The path tantra involves developing an attitude of richness and generosity. Confusion and pain are viewed as sources of inspiration, a rich resource. Furthermore, you acknowledge that you are intelligent and courageous, that you are able to be fundamentally alone. You are willing to have an operation without the use of anesthetics, constantly unfolding, unmasking, opening on and on and on. You are willing to be a lonely person, a desolate person, are willing to give up the company of your shadow, your twenty-four-hour-a-day commentator who follows you constantly, the watcher.

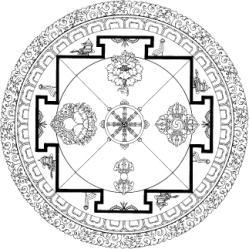

Mandala of the five buddha-wisdoms. These are the basic attributes of how enlightened mind perceives and manifests in the phenomenal world through the manner of the five wisdoms: wisdom of all-encompassing space, mirrorlike wisdom, wisdom of equanimity, discriminating-awareness wisdom, and wisdom of accomplishing all actions.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

In the Tibetan tradition the watcher is called

dzinba (’dzin pa),

which means “fixation” or “holding.” If we give up the watcher, then we have nothing left for which to survive, nothing left for which to continue. We give up hope of holding on to something. That is a very big step toward true asceticism. You have to give up the questioner and the answer—that is, discursive mind, the checking mechanism that tells you whether you are doing well or not doing well. “I am this, I am that.” “Am I doing all right, am I meditating correctly, am I studying well, am I getting somewhere?” If we give all this up, then how do we know if we are advancing in spiritual practice? Quite possibly there is no such thing as spiritual practice except stepping out of self-deception, stopping our struggle to get hold of spiritual states. Just give that up. Other than that there is no spirituality. It is a very desolate situation. It is like living among snowcapped peaks with clouds wrapped around them and the sun and moon starkly shining over them. Below, tall alpine trees are swayed by strong, howling winds and beneath them is a thundering waterfall. From our point of view, we may appreciate this desolation if we are an occasional tourist who photographs it or a mountain climber trying to climb to the mountain top. But we do not really want to live in those desolate places. It’s no fun. It is terrifying, terrible.

But it is possible to make friends with the desolation and appreciate its beauty. Great sages like Milarepa relate to the desolation as their bride. They marry themselves to desolation, to the fundamental psychological aloneness. They do not need physical or psychological entertainment. Aloneness becomes their companion, their spiritual consort, part of their being. Wherever they go they are alone, whatever they do they are alone. Whether they relate socially with friends or meditate alone or perform ceremonies together or meditate together, aloneness is there all the time. That aloneness is freedom, fundamental freedom. The aloneness is described as the marriage of shunyata and wisdom in which your perception of aloneness suggests the needlessness of dualistic occupation. It is also described as the marriage of shunyata and compassion in which aloneness inspires compassionate action in living situations. Such a discovery reveals the possibility of cutting through the karmic chain reactions that recreate ego-oriented situations, because that aloneness or the space of desolation does not entertain you, does not feed you anymore. Ultimate asceticism becomes part of your basic nature. We discover how samsaric occupations feed and entertain us. Once we see samsaric occupations as games, then that in itself is the absence of dualistic fixation, nirvana. Searching for nirvana becomes redundant at that point.

So at the beginning of the path we accept our basic qualities, which is ground tantra, and then we tread the path, which could be hot or cold, pleasurable or painful. In fruition tantra, which is beyond what we have discussed, we discover our basic nature. The whole process of the spiritual path, from the Buddhist point of view, is an organic one of natural growth: acknowledging the ground as it is, acknowledging the chaos of the path, acknowledging the colorful aspect of the fruition. The whole process is an endless odyssey. Having attained realization, one does not stop at that point, but one continues on, endlessly expressing buddha activity.

M

ANDALA

We found that in the mahayana or bodhisattva path there is still some kind of effort involved, not necessarily the effort of the heavy-handed ego, but there is still some kind of self-conscious notion that “I am practicing this, I am putting my effort into this.” You know exactly what to do, there is no hesitation, action happens very naturally, but some solid quality of ego is still present in a faint way. At that stage a person’s experience of shunyata meditation is very powerful, but still there is a need to relate to the universe more directly. This requires a leap rather than a disciplined effort, a generosity in the sense of willingness to open yourself to the phenomenal world, rather than merely being involved with a strategy of how to relate with it. Strategy becomes irrelevant and the actual perception of energy becomes more important.

One must transcend the ego’s strategies—aggression, passion, and ignorance—and become completely one with those energies. We do not try to remove or destroy them, but we transmute their basic nature. This is the approach of the vajrayana, the tantric or yogic path. The word

yoga

means “union,” complete identification, not only with the techniques of meditation and skillful, compassionate communication, but also with the energies that exist within the universe.

The word

tantra

means “continuity.” The continuity of development along the path and the continuity of life experience becomes clearer and clearer. Every insight becomes a confirmation. The symbolism inherent in what we perceive becomes naturally relevant rather than being another fascinating or interesting imposition from outside, as though it were something we had never known about before. Visual symbolism, the sound symbolism of mantra, and the mental symbolism of feeling, of energy, all become relevant. Discovering a new way of looking at experience does not become a strain or too potent; it is a natural process. Complete union with the energy of the universe and seeing the relationships of things to each other as well as the vividness of things as they are is the mandala principle.

Mandala

is a Sanskrit word that means “society,” “group,” “association.” It implies that everything is centered around something. In the case of the tantric version of mandala, everything is centered around centerless space in which there is no watcher or perceiver. Because there is no watcher or perceiver, the fringe becomes extremely vivid. The mandala principle expresses the experience of seeing the relatedness of all phenomena, that there is a continual cycle of one experience leading to the next. The patterns of phenomena become clear because there is no partiality in one’s perspective. All corners are visible, awareness is all-pervading.

The mandala principle of complete identification with aggression, passion, and ignorance is realized by practice of the father tantra, the mother tantra, and the union tantra. The father tantra is associated with aggression or repelling. By transmuting aggression, one experiences an energy that contains tremendous force. No confusion can enter into it; confusion is automatically repelled. It is called “vajra anger” since it is the diamondlike aspect of energy. Mother tantra is associated with seduction or magnetizing which is inspired by discriminating wisdom. Every texture of the universe or life is seen as containing a beauty of its own. Nothing is rejected and nothing is accepted but whatever you perceive has its own individual qualities. Because there is no rejection or acceptance, therefore the individual qualities of things become more obvious and it is easier to relate with them. Therefore discriminating wisdom appreciates the richness of every aspect of life. It inspires dancing with phenomena. This magnetizing is a sane version of passion. With ordinary passion we try to grasp one particular highlight of a situation and ignore the rest of the area in which that highlight is located. It is as if we try to catch a fish with a hook but are oblivious to the ocean in which the fish swims. Magnetizing in the case of mother tantra is welcoming every situation but with discriminating wisdom. Everything is seen precisely as it is, and thus there is no conflict. It does not bring indigestion. Union tantra involves transmuting ignorance into all-pervading space. In ordinary ignorance we try to maintain our individuality by ignoring our environment. But in the union tantra there is no maintenance of individuality. It is perception of the whole background of space, which is the opposite of the frozen space of ignorance.