The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (68 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Perceiving the energies of the buddha families in people and in situations, we see that confusion is workable and can be transformed into an expression of sacred outlook. The student must reach this understanding before the teacher can introduce the tantric deities, or yidams. Every yidam “belongs” to a buddha family and is “ruler” of the wisdom aspect of that family. The buddha family principles provide a link between ordinary samsaric experience and the brilliance and loftiness of the yidams’ world. By understanding the buddha family principles, we can appreciate the tantric deities as embodiments of the energies of sacred world and identify ourselves with that sacredness. With that understanding we can receive abhisheka, or empowerment; we are ready to be introduced to Vajrayogini.

A

BHISHEKA

By receiving the abhisheka of Vajrayogini, the student enters the mandala of Vajrayogini. Through this process, Vajrayogini becomes one’s yidam—the embodiment of one’s basic being or basic state of mind.

Abhisheka,

which is Sanskrit, literally means “anointment.” The Tibetan

wangkur

means “empowerment.” The principle of empowerment is that there is a meeting of the minds of the student and vajra master, which is the product of devotion. Because the student is able to open fully to the teacher, the teacher is able to communicate directly the power and wakefulness of the vajrayana through the formal ceremony of abhisheka. In reviewing the history of the Vajrayogini transmission in the Karma Kagyü lineage, the directness of this communication becomes apparent.

VAJRAYOGINI’S SYMBOLIC MEANING

T

HE

V

AJRAYOGINI

S

ADHANA IN THE

K

ARMA

K

AGYÜ

L

INEAGE

The abhisheka of Vajrayogini is an ancient ceremony which is part of the

Vajrayogini Sadhana,

the manual and liturgy of Vajrayogini practice. There are many sadhanas of Vajrayogini, including those according to Saraha, Nagarjuna, Luyipa, Jalandhara, and Shavari. In the Karma Kagyü tradition, one practices the sadhana of Vajrayogini according to the Indian siddha Tilopa, the forefather of the Kagyü lineage.

According to spiritual biographies, after studying the basic Buddhist teachings for many years, Tilopa (998–1069

C.E.

) traveled to Uddiyana, the home of the dakinis, or female yidams, to seek vajrayana transmission. He gained entrance to the palace of the dakinis and received direct instruction there from Vajrayogini herself, who manifested to him as the great queen of the dakinis. It may be rather perplexing to speak of encountering Vajrayogini in anthropomorphic form, when she is discussed throughout this article as the essence of egolessness. However, this account of Tilopa’s meeting is the traditional story of his encounter with the direct energy and power of Vajrayogini.

Naropa (1016–1100), who received the oral transmission of the Vajrayogini practice from Tilopa, was a great scholar at Nalanda University. Following a visit from a dakini who appeared to him as an ugly old hag, he realized that he had not grasped the inner meaning of the teachings, and he set out to find his guru. After encountering many obstacles, Naropa found Tilopa dressed in beggar’s rags, eating fish heads by the side of a lake. In spite of this external appearance, Naropa at once recognized his guru. He remained with him for many years and underwent numerous trials before receiving final empowerment as the holder of his lineage.

From Naropa, the oral tradition of the Vajrayogini practice passed to Marpa (1012–1097), the first Tibetan holder of the lineage. Marpa made three journeys from Tibet to India to receive instruction from Naropa. It is said that, during his third visit to India, Marpa met Vajrayogini in the form of a young maiden. With a crystal hooked knife she slashed open her belly, and Marpa saw in her belly the mandala of Vajrayogini surrounded by a spinning mantra wheel. At that moment, he had a realization of Vajrayogini as the Coemergent Mother, a principle that will be discussed later. This realization was included in the oral transmission of Vajrayogini, which has been passed down to the present day.

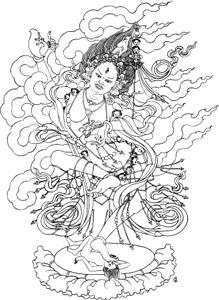

Vajrayogini: The Sovereign of Desire.

Marpa gave the oral instructions for the Vajrayogini practice to the renowned yogin Milarepa (1040–1123); he in turn transmitted them to Gampopa (1079–1153), a great scholar and practitioner who established the monastic order of the Kagyü. Chief among Gampopa’s many disciples were the founders of the “four great and eight lesser schools” of the Kagyü tradition. The Karma Kagyü, one of the four great schools, was founded by Tusum Khyenpa (1110–1193), the first Karmapa and a foremost disciple of Gampopa. Since that time, the Karma Kagyü lineage has been headed by a succession of Karmapas, numbering sixteen in all. Tüsum Khyenpa handed down the oral transmission of the

Vajrayogini Sadhana

to Drogön Rechenpa (1088–1158); from him it was passed to Pomdrakpa, who transmitted it to the second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi (1206–1283). Karma Pakshi passed the Vajrayogini transmission to Ugyenpa (1230–1309), who gave it to Rangjung Dorje (1284–1339), the third Karmapa. It was Rangjung Dorje, the third Karmapa, who composed the written form of the sadhana of Vajrayogini according to Tilopa and the oral instructions of Marpa, which is still practiced today. It is this sadhana that is the basis for this discussion of the Vajrayogini principle.

The first Trungpa was a student of the siddha, Trung Mase (fifteenth century), who was a close disciple of the fifth Karmapa, Teshin Shekpa (1384–1415). When Naropa transmitted the teachings of Vajrayogini to Marpa, he told him that these teachings should be kept as a transmission from one teacher to one student for thirteen generations, and then they could be propagated to others. This transmission is called chig gyü, the “single lineage” or “single thread” transmission. Because of this, the Kagyü lineage is frequently called the “hearing lineage.” Trung Mase received the complete teachings on Vajrayogini, Chakrasamvara, and the Four-Armed Mahakala, and these became a special transmission that he was to hold. Since Trung Mase belonged to the thirteenth generation, he became the first guru to transmit this particular lineage of mahamudra teachings to more than a single dharma successor, and in fact he taught it widely. The first Trungpa, Künga Gyaltsen, was one of Trung Mase’s disciples who received this transmission. As the eleventh Trungpa Tulku, I received the Vajrayogini transmission from Rölpa Dorje, the regent abbot of Surmang and one of my main tutors.

Since 1970, when I arrived in America, I have been working to plant the buddhadharma, and particularly the vajrayana teachings, in American soil. Beginning in 1977 and every year since then, those of my students who have completed the preliminary vajrayana practices, as well as extensive training in the basic meditative disciplines, have received the abhisheka of Vajrayogini. As of 1980 there are more than three hundred Vajrayogini sadhakas (practitioners of the sadhana) in our community, and there are also many Western students studying with other Tibetan teachers and practicing various vajrayana sadhanas. So the Vajrayogini abhisheka and sadhana are not purely part of Tibetan history; they have a place in the history of Buddhism in America as well.

T

HE

C

EREMONY OF

A

BHISHEKA

The abhisheka of Vajrayogini belongs to the highest of the four orders of tantra: anuttaratantra.

Anuttara

means “highest,” “unsurpassed,” or “unequaled.” Anuttaratantra can be subdivided into three parts: mother, father, and nondual. The Karma Kagyü lineage particularly emphasizes the teachings of the mother tantra, to which Vajrayogini belongs.

Mother tantra stresses devotion as the starting point for vajrayana practice. Therefore, the key point in receiving the abhisheka is to have one-pointed devotion to the teacher. By receiving abhisheka, one is introduced to the freedom of the vajra world. In the abhisheka, the vajra master manifests as the essence of this freedom, which is the essence of Vajrayogini. He therefore represents the yidam as well as the teacher in human form. Thus, when one receives abhisheka, it is essential to understand that the yidam and the guru are not separate.

In the tradition of anuttaratantra, the student receives a fourfold abhisheka. The entire ceremony is called an abhisheka, and each of the four parts is also called an abhisheka, because each is a particular empowerment. The four abhishekas are all connected with experiencing the phenomenal world as a sacred mandala.

Before receiving the first abhisheka, the student reaffirms the refuge and bodhisattva vows. At this point the attitude of the student must be one of loving-kindness for all beings, with a sincere desire to benefit others. The student then takes a vow called the samaya vow, which binds the teacher, the student, and the yidam together. As part of this oath, the student vows that he or she will not reveal his or her vajrayana experience to others who are not included in the mandala of Vajrayogini. The student then drinks what is known as the samaya oath water from a conch shell on the shrine, to seal this vow. It is said that if the student violates this oath the water will become molten iron: it will burn the student from within and he will die on the spot. On the other hand, if the student keeps his vow and discipline, the oath water will act to propagate the student’s sanity and experience of the glory, brilliance, and dignity of the vajra world. The notion of samaya will be discussed in greater detail after the discussions of the abhisheka itself.

After taking the samaya oath, the student receives the first abhisheka, the abhisheka of the vase (kalasha abhisheka), also known as the water abhisheka. Symbolically, the abhisheka of the vase is the coronation of the student as a prince or princess—a would-be king or queen of the mandala. It signifies the student’s graduation from the ordinary world into the world of continuity, the tantric world.

The abhisheka of the vase has five parts, each of which is also called an abhisheka. In the first part, which is also called the abhisheka of the vase, the student is given water to drink from a vase on the shrine, called the tsobum. The tsobum is the principal abhisheka vase and is used to empower the student. The text of the abhisheka says:

Just as when the Buddha was born

The devas bathed him,

Just so with pure, divine water

We are empowered.

Receiving the water from the tsobum in the first abhisheka of the vase symbolizes psychological cleansing as well as empowerment. Before ascending the throne, the young prince or princess must bathe and put on fresh clothes. The five abhishekas of the vase are connected with the five buddha families. The first abhisheka of the vase is connected with the vajra family; the student is presented with a five-pointed vajra scepter, symbolizing his ability to transmute aggression into mirrorlike wisdom.