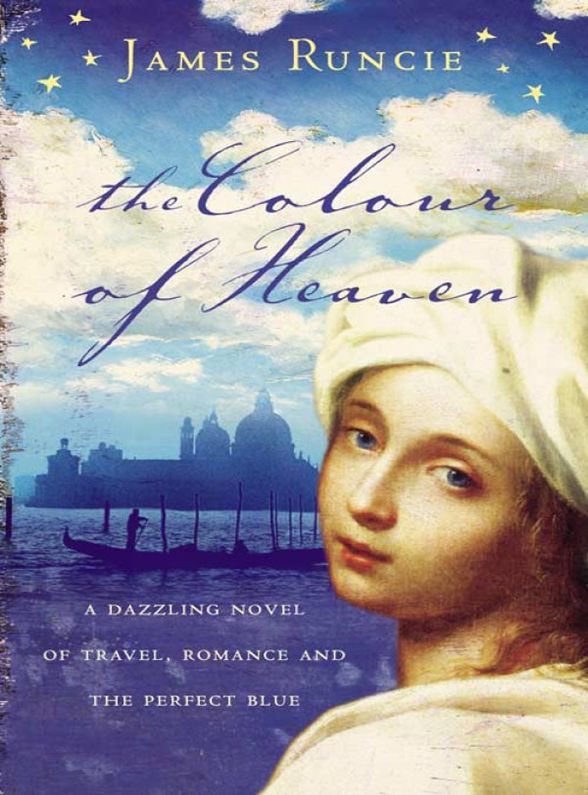

The Colour of Heaven

Read The Colour of Heaven Online

Authors: James Runcie

THE COLOUR OF

HEAVEN

for Marilyn

Sapphire, nor diamond, nor emerald,

Nor other precious stones past reckoning,

Topaz, nor pearl, nor ruby like a king,

Nor that most virtuous jewel, jasper call’d,

Nor amethyst, nor onyx, nor basalt,

Each counted for a very marvellous thing,

Is half so excellently gladdening

As is my lady’s head uncoronall’d.

All beauty by her beauty is made dim;

Like to the stars she is for loftiness;

And with her voice she taketh away grief.

She is fairer than a bud, or than a leaf.

Christ have her well in keeping, of His grace,

And make her holy and beloved, like Him!

Jacopo da Lentino, 1250

Translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

No one noticed the child.

He had been left in a small boat which now sailed out towards the lagoon, following nothing but the slap and tide of each narrow canal.

It was Ascension Day in the year twelve hundred and ninety-five, and the people of Venice were parading through the streets, hoisting crimson pennants and bright-yellow banners in celebration. Tailors dressed in white tunics with crimson stars, weavers in silver cloth tippets, and cotton spinners in cloaks of fustian mingled with blacksmiths, carpenters, butchers, and bakers, singing and shouting their way towards the Piazza San Marco.

The square was filled with showmen, swindlers, soothsayers, and charlatans; jesters, jugglers, prophets, and priests. Alchemists cried out that scrapings of amber gave protection from the plague, and that an emerald pressed against naked flesh could preserve a woman from apoplexy. A dentist with silver teeth sold a special compound which he vowed would improve the value of all metal; a barber displayed a gum to make bald men hirsute; and a naked Englishman sold pine seeds which were said to guarantee invisibility as surely as the talisman of Gyges.

But no one had noticed the baby.

Teresa could have ignored him, another abandoned child due for an early death at the Foundlings’ Hospital; but once she had seen him the shock of love took hold.

She watched the boat spin gently against the side of a little

rio

, caught in a momentary eddy, as if waiting only for her arrival. Perhaps this was a gift from God at last, alleviation for all that she had suffered.

She looked around, for mother or father, doctor or stranger, but amidst the movement of the crowd they were the only people to be still, the abandoned baby and the woman who could never have children: Teresa, wife of Marco the glass-maker, barren. No other adjective was necessary. Her pale-blue eyes, thin frame, and slender beauty meant nothing. When people wanted to describe her, they spoke but the one word: barren.

She knelt down beside the waters and gathered in the child.

‘Calme, calme, mio bambino.’

The baby’s mouth began to pucker, longing for milk.

Teresa knew that she should go into the church and ask the priest what to do but at that moment the doors swung open and a vast procession emerged, singing Psalms and praising God. She let the pageant go by, watching a group of children carrying silver bowls filled with rose petals, whispering and squabbling as they passed.

Teresa tried to convince herself that she did not need the child. She should leave him, as his mother had left him, and as hundreds of other mothers would do on this very day throughout the city. Children were a drain, and a curse, the punishment for sexual excess. They cried. They were always hungry. They grew up to take your money and denounce you. That was what Marco had always told her: her husband, who could, in fact, be as barren as she. They had never known.

She could hear his voice telling her to put the baby back, leaving it either for charity, another mother, or death. What was one child more or one child less in the world when we are born only to live, suffer, and die?

She sat down on the steps of the church.

The child was so pale and so fair.

Out in the lagoon, trumpeters, troubadours, and drummers sailed past the Doges’ Palace singing of beauty and lost love, saluting both the rising and the setting of the sun, mothers and daughters, mistresses and maids, the besotted and the beloved.

Some of the boats were preparing tableaux of the Christian mysteries: the shipwrights and carpenters were to re-enact Noah’s flood; the vintners would create the illusion of Christ turning the water into wine, whereas Marco’s single-sailed

sandolo

had been transformed into a moveable theatre in which his fellow glass-makers would perform ‘The harrowing of hell’.

His friends were dressed as heavy-drinking devils with horns made from old fish baskets, and their blowpipes had become instruments of diabolic torture. Marco was to play the devil himself. He stood on the prow, his smoky frame dominating the boat, and bellowed a list of the torments awaiting all sinners. Rival guilds watched in wonder as Marco blew flames, drank, shouted, and sang of terror and disaster. The nearer other boats sailed, the more dramatic his gestures became until he could resist temptation no longer and began to describe the precise location of the mouth of hell.

He turned round, bent over, and mooned at all who might look at him, shouting:

‘Guarda! Guarda!

La bocca d’inferno è nel mio culo!’

Encouraged by his companions, he then provided a triumphant auditory accompaniment to the gesture.

‘Ecco un fracasso del diavolo!’

The longer the day lasted, and the more red wine they drank, the funnier such antics seemed, until the time came for the youngest glass-maker to harrow hell. Young Pietro emerged from beneath the sail (which now became the flag of Resurrection) carrying a vast glass crucifix and shouted:

‘We have blown this crucifix as surely as Christ will blast away the gates of Death.’

He then struck his fellow workers with the cross, and they dived into the waters of the lagoon, an improbable reminder of the power of baptism and redemption.

‘This sky is our heaven, these waters our home. Let no one deny the promises we have been vouchsafed!’ Pietro shouted.

The Doge’s gilded barge, the

Bucintoro

, sailed past the spluttering glass-makers in preparation for the ceremonial marriage of Venice to the sea. The boat moved out towards the Lido, canopied in red, shining with golden river gods, zephyrs, putti, and mermaids, the Lion of St Mark fluttering above.

The Doge rose to the prow of his ship and took the ceremonial glass ring from his finger.

Then he proclaimed,

‘O Sea, we wed thee in sign of our everlasting dominion,’

and threw the ring out into the Adriatic.

The

Bucintoro

turned back, its oars gleaming in the light. Marco and his men, now safely back on board their boat, raised a

fiasco

of wine, as if toasting their leader, and prepared to sail back to Murano, content with their day’s display.

As they did so, Teresa opened her blouse and pinched at her breast. The child squirmed in her arms. She would have to take the baby to her sister, for, whereas Teresa could not even begin to conceive, Francesca could not stop having children. The milk poured out of her so much that she worked as a wet nurse to sustain her family.

Teresa began to walk up towards the Misericordia. She watched the crowd stream over the bridges, returning home to eat and drink before the curfew, ready to share their thoughts about the day, to joke perhaps, to laugh, even to make love.

Boats headed out into the lagoon.

At first her sister thought she was carrying the baby on a mission from another mother. ‘Where is it from?’

‘I do not know.’

‘What have you done?’

‘I have a child at last.’

‘How?’

Teresa tried to remain defiant. ‘I found it. By the Church of the Apostles.’

Francesca could not believe such folly. ‘If I had known you were desperate you could have raised one of mine.’

‘I didn’t want one of yours. I wanted one of my own.’

‘Is it a boy or a girl?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You didn’t check? Here. Let me look.’

Teresa handed her sister the child.

‘It’s a boy. He needs feeding.’ Francesca opened her blouse and took the baby to her breast. He drank noisily, hungrily. Teresa watched the child suck and felt the first stirrings of jealousy.

‘I always knew you would do something stupid.’

‘It’s not stupid. Look at him.’

‘You’ll have to pay me,’ Francesca demanded.

The two sisters looked at the child, feeding greedily, possessed by need. Teresa was surprised for the first time by the noise: the spluttering and the gasping, the desire and the power of a baby at the breast sucking for life itself. ‘Does it hurt?’ she asked.

‘Of course it does. But you get used to it. He’s feeding well. Then he’ll be sick.’

‘Sick?’

‘You’ve been spared all this: the milk and pain of motherhood, the jealous husband, the cries in the night. Disease. Illness. Death. What do you want a child for?’

‘Joy,’ said Teresa. ‘I want him for joy.’

Marco had drunk several flasks of wine by the time he rowed alongside the Fondamenta Santa Caterina to collect his wife. At times he could not believe that he was married to this woman. He wondered whether he should have wed her sister, a woman with plenty of flesh on her, proper breasts, firm hips, and a body in which a man could lose himself. But did he want all those babies and all that milk? He held his flask of wine aloft in greeting.

Teresa shivered nervously, and gave him a small wave. That is my husband, she thought, as if the events of the day had made them strangers both to the city and to each other. They had never looked as if they belonged together: Teresa thin, anxious, and bird-like; her husband broad, swarthy, and muscular, like Vulcan or some dark river god.

‘Did you watch?’ he asked.

Teresa had forgotten that she might have to lie. ‘There were so many people. And you were far away.’

‘I told you that you should have come with us.’

‘There was not room. It was for men. You know that.’

‘It would not have mattered.’

‘Did you see the Doge?’ asked Teresa.

‘I did. And he saw us. It was a triumph.’

As her husband recounted the story of the day, Teresa realised that she could not take in what he was saying. She could think only of the child. Perhaps she should tell him now, she thought, in this stillness, out in the lagoon. She should confess, or even shout out, that the baby was the only thing that mattered to her, more important than either his love or her own death.

She wondered what it would be like to tell him. She almost wanted to laugh with the joy of it all, sharing this new happiness with the man she loved. But she knew that Marco would be fearful, his mood would change, and that it would ruin the day. He would talk about money. He would ask her to take the child back. And he would not give the real reason for his fear: the fact that a son might change their marriage, that they would no longer be alone.

He put out a line and began to fish.

As the boat rocked on the water, Teresa remembered holding the child in her arms. Although she ached for him, she knew that she must hide the fact, as if the revelation of such a secret would only destroy its beauty.

At last there was movement on the line and Marco flicked up a sturgeon, its back gleaming against the dying light, twitching in midair before being cast down onto the floor of the boat.

‘

E basta

,’ Marco cried, still happy.

A wind started up, blowing across the lagoon. Teresa watched her husband pull in the line and begin to row harder for the island.

‘Did you gather the wood this morning?’ he asked.

Teresa knew the question mattered, but could not remember why. ‘Alder,’ she replied.

‘Enough for tonight and tomorrow?’