Read The Complete Compleat Enchanter Online

Authors: L. Sprague deCamp,Fletcher Pratt

The Complete Compleat Enchanter (18 page)

Sir Erivan looked at him in some astonishment. “You are pleased to jest—No, I see you are really a foreigner and don’t know. Well, then, such is the custom of Faerie. But I misdoubt me these enchanters and their spells.” He shook his head gloomily.

Shea said: “Say, my friend Chalmers and I might be able to help you out a little.”

“In what manner?”

Chalmers was making frantic efforts to signal him to silence, but Shea ignored them. “We know a little magic of our own. Pure white magic, like that Lady Cambina you spoke of. For instance—Doc, think you could do something about the wine situation?”

“Why . . . ahem . . . that is . . . I suppose I might, Harold. But don’t you think—”

Shea did not wait for the objection. “If you’ll be patient,” he said, “my friend the palmer will work some of his magic. What’ll you need, Doc?”

Chalmers’ brow furrowed. “A gallon or so of water, yes. Perhaps a few drops of good wine. Some grapes and bay leaves—”

Somebody interrupted: “As well ask for the moon in a basket as grapes at Caultrock. Last week came a swarm of birds and stripped the vines bare. Enchanter’s work, by hap; they do not love us here.”

“Dear me! Would there be a cask?”

“Aye, marry, a mort o’ ’em. Rudiger, an empty cask!”

The cask was rolled down the center of the tables. The guests buzzed as they saw the preparations. Other articles were asked and refused till there was produced a stock of cubes of crystallized honey, crude and unstandardized in shape, “—but they’ll do as sugar cubes, lacking anything better,” Chalmers told Shea.

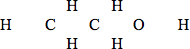

A piece of charcoal served Chalmers for a pencil. On each of the lumps of crystallized honey he marked a letter, O, C, or H. A little fire was got going on the stone floor in the center of the tables. Chalmers dissolved some of the honey in some of the water, put the water in the cask and some of the straw in the water. The remaining lumps of honey he stirred about the table top with his fingers, as though playing some private game of anagrams, reciting meanwhile:

“So oft as I with state of present time

The image of our . . . uh . . . happiness compare,

So oft I find how less we are than prime,

How less our joy than that we once did share:

Thus do I ask those things that once we had

To make an evening run its wonted course,

And banish from this company the sad

Thoughts that in utter abstinence have their source:

Change then! For, being water, you cannot be worse!”

As he spoke, he withdrew a few of the lumps, arranging them thus:

“By the splendor of Heaven!” cried a knight with a short beard, who had risen and was peering into the cask. “The palmer’s done it!”

Chalmers reached over and pulled the straw from the top of the cask, dipped some of the liquid into his goblet and sipped. “God bless my soul!” he murmured.

“What is it, Doc?” asked Shea.

“Try it,” said Chalmers, passing him the goblet.

Shea tried it, and for the second time that evening almost upset the table.

The liquid was the best Scotch whiskey he had ever tasted.

The thirsty Sir Erivan spoke up: “Is aught amiss with your spell-wrought wine?”

“Nothing,” said Chalmers, “except that it’s rather . . . uh . . . potent.”

“May one sample it, Sir Palmer?”

“Go easy on it,” said Shea, passing down the goblet.

Sir Erivan went easy, but nevertheless exploded into a series of coughs.

“Whee!

A beverage for the gods on Olympus! None but they would have gullets of the proper temper. Yet methinks I should like more.”

Shea diluted the next slug of whiskey with water before giving it to the serving man to pass down the table. The knight with the short beard made a face at the flavor. “This tastes like no wine I wot of,” said he.

“Most true,” said Erivan, “but ’tis proper nectar, and makes one feel wonnnnnnderful! More, I pray you!”

“May I have some, please?” asked Amoret, timidly.

Chalmers looked unhappy. Britomart intervened: “Before you sample strange waters I myself will try.” She picked up the goblet she was sharing with Shea, took a long quick drink.

Her eyes goggled and watered, but she held it well. “Too . . . strong for my little charge,” said she when she got her breath back.

“But, Lady Britomart—”

“Nay. It would not—Nay, I say.”

The servitors were busy handing out the Scotch, which left a trail of louder talk and funnier jokes in its wake. Down the table some of the people were dancing; the kind of dance wherein you spend your time holding up your partner’s hand and bowing. Shea had just enough whiskey in him to uncork his natural recklessness. He bowed half-mockingly to Britomart. “Would my lady care to dance?”

“No,” she said solemnly. “I do it not. So many responsibilities have I had that I’ve never learned. Another drink, please.”

“Oh, come on! I don’t, either, the way they do here. But we can try.”

“No,” she said. “Poor Britomart never indulges in the lighter pleasures. Always busy, righting wrongs and setting a good example of chastity. Not that anyone heeds it.”

Shea saw Chalmers slip Amoret a shot of whiskey. The perfect beauty coughed it down. Then she began talking very fast about the sacrifices she had made to keep herself pure for her husband. Chalmers began looking around for help. Serves the Doc right, thought Shea. Britomart was pulling his sleeve.

“It’s a shame,” she sighed. “They all say Britomart needs no man’s sympathy. She’s the girl who can take care of herself.”

“Is it as bad as all that?”

“Mush worst. I mean much worse. They all say Britomart has no sense of humor. That’s because I do my duty. Conscientious. That’s the trouble. You think I have a sense of humor, don’t you, Master Harold de Shea?” She looked at him accusingly.

Shea privately thought that “they all” were right. But he answered: “Of course I do.”

“That’s splendid. It gladdens my heart to find someone who understands. I like you, Master Harold. You’re tall, not like these little pigs of men around here. Tell me,

you

don’t think I’m too tall, do you? You wouldn’t say I was just a big blond horse?”

“Perish the thought!”

“Would you even say I was good-looking?”

“And how!” Shea wondered how this was going to end.

“Really, truly good-looking, even if I am tall?”

“Sure, you bet, honest.” Shea saw that Britomart was on the verge of tears. Chalmers was busy trying to stanch Amoret’s verbal hemorrhage, and couldn’t help.

“Thass glorious. I’m so glad to find somebody who likes me as a woman. They all admire me, but nobody cares for me as a woman. Have to set a good example. Tell you a secret.” She leaned toward him in such a marked manner that Shea glanced around to see whether they were attracting attention.

They were not. Sir Erivan, with a Harpo Marx expression, was chasing a plump, squeaking lady from pillar to pillar. The dancers were doing a snake dance. From one corner came a roar where knights were betting their shirts at knucklebones.

“Tell you shecret,” she went on, raising her voice. “I get tired of being a good example. Like to be really human. Just once. Like this.” She grabbed Shea out of his seat as if he had been a puppy dog, slammed him down on her lap, and kissed him with all the gentleness of an affectionate tornado.

Then she heaved him out of her lap with the same amazing strength and pushed him back into his place.

“No,” she said gloomily. “No. My responsibilities. Must think on them.” A big tear rolled down her cheek. “Come, Amoret. We must to bed.”

###

The early sun had not yet reached the floor of the courtyards when Shea came back, grinning. He told Chalmers: “Say, Doc, silver has all kinds of value here! The horse and ass together only cost $4.60.”

“Capital! I feared some other metal would pass current, or that they might have no money at all. Is the . . . uh . . . donkey domesticated?”

“Tamest I ever saw. Hello, there, girls!” This was to Britomart and Amoret, who had just come out. Britomart had her armor on, and a stern, martial face glowered at Shea out of the helmet.

“How are you this morning?” asked that young man, unabashed.

“My head beats with the cruel beat of an anvil, as you must know.” She turned back. “Come, Amoret, there is no salve like air, and if we start now we shall be at Satyrane’s castle as early as those who ride late and fast with more pain.”

“We’re going that way, too,” said Shea. “Hadn’t we better ride along with you?”

“For protection’s sake, mean you? Hah! Little enough use that overgrown bodkin you bear would be if we came to real combat. Or is it that you wish to ride under the guard of my arm?” She shook it with a clang of metal.

Shea grinned. “After all, you

are

technically my ladylove—” He ducked as she swung at him, and hopped back out of reach.

Amoret spoke up: “Ah, Britomart, but do me the favor of letting them ride with us! The old magician is so sympathetic.”

Shea saw Chalmers start in dismay. But it was too late to back out now. When the women had mounted they rode through the gate together. Shea took the lead with the grumpily silent Britomart. Behind him, he could hear Amoret prattling cheerfully at Chalmers, who answered in monosyllables.

The road, no more than a bridle path without marks of wheeled traffic, paralleled the stream. The occasional glades that had been visible near Castle Caultrock disappeared. The trees drew in on them and grew taller till they were riding through a perpetual twilight, only here and there touched with a bright fleck of sunlight.

After two hours Britomart drew rein. As Amoret came up, the warrior girl announced: “I’m for a bath. Join me, Amoret?”

The girl blushed and simpered. “These gentlemen—”

“Are gentlemen,” said Britomart, with a glare at Shea that implied he had jolly well better be a gentleman, or else. “We will halloo.” She led the way down the slope and between a pair of mossy trunks.

The two men strolled off a way and sat. Shea turned to Chalmers. “How’s the magic going?”

“Ahem,” said the professor. “We were right about the general worsening of conditions here. Everyone seems aware of it, but they don’t quite know what causes it or what to do about it.”

“Do you?”

Chalmers pinched his chin. “It would seem—uh—reasonable to suspect the operations of a kind of guild of evil, of which various enchanters, like this Busyrane mentioned last night, form a prominent part. I indicate the souring of the wine and the loss of the grapes as suggestive examples. It would not even surprise me to discover that a well-organized revolutionary conspiracy is afoot. The question of whether such a subversive enterprise is justified is of course a moral one, resting on that complex of sentiments which the German philosophers call by the characteristically formidable name of

Weltansicht.

It therefore cannot be settled by scientific—”

Shea said: “Yeah. But what can we do about it?”

“I’m not quite certain. The obvious step would be to observe some of these people in operation and learn something of their technique. This tournament—Good gracious, what’s that?”

From the river came a shriek. Shea stared at Chalmers for three seconds. Then he jumped up and ran toward the sound.

As he burst through the screen of brush, he saw the two women up to their necks in a little pool out near the middle of the river. Wading toward them, their backs to Shea, were two wild-looking, half-naked men in tartan kilts. They were shouting with laughter.

Shea did a foolish thing. He drew his épée, slid down the six-foot bank, and plowed into the water after the men, yelling. They whirled about, whipped out broadswords from rawhide slings, and splashed toward him. He realized his folly: knee-deep in water he would be unable to use his footwork. At best his chances were no more than even against one of these men. Two . . .

The bell-guard of the épée gave a clear ringing note as he parried the first cut. His riposte missed, but the kilted man gave a little. Shea out of the tail of his eye saw the other working around to get behind him. He parried, thrust, parried.

“Wurroo!” yelled the wild man, and swung again. Shea backed a step to bring the other into his field of vision. Cold fear gripped him lest his foot slip on an unseen rock. The other man was upon him, swinging his sword up with both hands for the kill. “Wurroo!” he yelled like the other. Shea knew sickeningly that he couldn’t get his guard around in time. . . .

Thump!

A rock bounced off the man’s head. The man sat down. Shea turned back to the first and just parried a cut at his head. The first kiltie was really boring in now. Shea backed another step, slipped, recovered, parried, and backed. The water tugged at his legs. He couldn’t meet the furious swings squarely for fear of snapping his light blade. Another step back, and another, and the water was only inches deep. Now! Disengage, double, one-two, lunge—and the needlepoint slid through skin and lungs and skin again. Shea recovered and watched the man’s knees sag. Down he went.

The other was picking himself out of the water some distance down. When Shea took a few steps toward him, he scrambled up the bank and ran like a deer, his empty swordsling banging against his back.