Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (4 page)

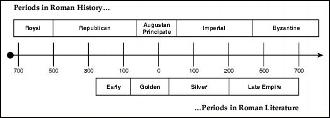

In this book, we'll investigate all these aspects of Rome and the Romans. To start, however, it helps to have a scholar's basic framework of the periods of Roman history

and literature. So let's get a handle on what these periods are called and (broadly) what happened during them. Historical and literary periods don't precisely overlap, so I've included a rough outline of each. From these outlines, we'll go into more depth in the following chapters.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

The Royal period refers to the time when kings ruled Romeâthat is, from whenever Rome became a ruled city, sometime between 800 and 700

B

.

C

.

E

., to when the Etruscan kings were deposed, ca 509

B

.

C

.

E

. Rome was never again ruled by a king although Senators accused Julius Caesar of trying to do so before they assassinated him. During this period, Rome grew from established settlements on the Tibur River (traditionally 753

B

.

C

.

E

.) into one of the most powerful cities in central Italy. The Royal and very early Republic is sometimes referred to as the Archaic period.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

The Republican period begins with the establishment of the Roman Republic (traditionally 509

B

.

C

.

E

.), which followed the overthrow of the kings. Not much is known about the early Republic although it's clear that internal and external strife were constant problems. Nevertheless, Rome started with its troublesome neighbors and went on to conquer what would today be northern and southern Italy, all of north Africa, Egypt, Spain, France, most of Britain, Switzerland, Austria, the Balkans, Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Ar-menia, and most of the Middle East.

Intense civil unrest marked the final century of the Republic. Beginning in 133

B

.

C

.

E

., there were a series of civil disturbances and wars between competing factions and generals: the Gracchus brothers and the Senate, the generals Marius and Sulla, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, and finally Octavian and Antony. This last conflict, fought in the aftermath of Julius Caesar's assassination, brought about the collapse of the Republic. Octavian, Caesar's adopted son, was victorious over Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31

B

.

C

.

E

. His return to Rome in 27

B

.

C

.

E

. is the traditional end of the Republic.

B

.

C

.

E

.â

C

.

E

. 14)

The Principate is technically the period between the Republic and the Dominate of Diocletian (

C

.

E

. 284) when Rome's ruler was known as the

princeps

. Generally, however, it refers to the transitional rule of Augustus between Republic and Empire. Octavian, victorious over Anthony and Cleopatra in 31

B

.

C

.

E

. claimed to restore the Republic, and in some ways he did. But otherwise, Octavian reorganized the Roman state so that he maintained a delicate balance between old ways and authoritarian rule until his death in

C

.

E

. 14. Octavian was awarded the name Augustus (“reverent and solemn”) and the title

Princeps

(“first among his peers”). His successors adopted this title from which the period gets its name. Under Augustus, Rome, both as a city and as an empire, flourished in a period of relative peace and stability.

C

.

E

. 14â476)

The Imperial Age or Empire period begins with the death of Augustus. During the Empire, successions of emperorsâboth good and badâruled over the vast Roman dominions until the Emperor Diocletian split the Empire into two parts in 284. Constantine the Great reunited the Empire and moved the capital to Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) in 330 and made Christianity the official Roman religion.

From this point, continuing pressure from Goths, Attila the Hun, the Vandals, economic and social stagnation, and other factors combined to send the crumbling west teetering toward the Dark Ages. The traditional end date for the fall of the western Empire was set by Edward Gibbon in 1776 in his monumental work,

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

He established the date as 476 when Germanic mercenaries deposed Romulus Augustulus and made their leader, Odoacer, emperor. Even though he was recognized by the eastern Emperor Zeno, Odoacer marks the point at which the western Roman Empire slides over the line from being a remnant of the Roman Imperial system into becoming a patchwork of Germanic kingdoms.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Two terms for political authorities come from this period as a result of Augustus's nebulous position. The first is Augustus's title of

Imperator

(commander) from which we get “Emperor.” The second is his title of

Princeps

(“First Citizen”) from which we get “Prince.”

Â

Roamin' the Romans

If you travel to northern Italy, be sure to visit Ravenna, the Ostrogoth capital where western emperors lived since Honorius (395â423) and where Theodoric is buried. Justinian's forces took the city in 540. His archbishops Maximian and Agnellus built or refurbished the churches of San Vitale, St. Apollinare in Classe, and St. Apollinare Nuovo. These churches and their world-famous mosaics remain as reminders of Justinian's attempt to reunite the Roman Empire and to elevate Ravenna above Rome as the new capital of the west.

The eastern half of the Empire tried to reestablish control under the Emperor Justinian (532â565). His efforts failed, and with his death the eastern Empire turned to soldier on alone for another thousand years.

People don't often think of the Byzantine culture as “Roman.” Greek, not Latin, was the language of the realm and the Orthodox Church developed apart from the Latin Roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless, the culture we know as Byzantine was the continuation of the eastern Roman Empire and saw itself in that light. Citizens called themselves

Romaioi

(Romans) and recognized their emperor as the legitimate Roman emperor in the “New Rome,” Constantinople.

Â

When in Rome

Byzantium

refers to the civilization that developed from the eastern Empire after the death of the emperor Justinian (

C

.

E

. 565).

Constantinople was first sacked in 1204 by its Latin Christian brothers in the Crusades and then taken by the Muslims in 1453. Refugees and migrants from

Byzantium

brought Greek literature and learning with them to Italian cities such as Venice and Florence and helped to fuel the emerging Italian Renaissance.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

The city of Byzantium was founded by Greeks around 667

B

.

C

.

E

. Torn back and forth between Greeks and Persians in the classical period, the city remained Greek until captured by the Romans in

C

.

E

. 196. Constantine refounded the city as “New Rome” in 330, but it quickly became known as “Constantine's city,” or Constantinopole. The modern name, Istanbul, reportedly comes from the Greek

eis tÄn polin

, which means “to the city.” This was apparently the common answer to a question, “So, where ya' headed?” asked of Greeks traveling along the provincial roads for over a thousand years.

Latin literature was slow out of the blocks in comparison to other cultures such as the Greeks. Homer's

Iliad

and

Odyssey,

for example, were composed sometime around 750

B

.

C

.

E

., just about the same time as the traditional date of the founding of Rome. Classical Greek literature hit its high point roughly between 450â350

B

.

C

.

E

. during the time when the Roman Republic was tottering about on its first marching legs. It

wasn't until the mid-third century (300â200)

B

.

C

.

E

. that the Romans began to cultivate a literature of their own.

A comparative timeline of Roman history and literature.

There are several reasons for the late start. First, the Romans were a practical people focused on action. They saw themselves as hard-working, hard-fighting, practical, salt-of-the-earth farmers who had little time for literature and other idle-headed activities. Romans, in the public sphere, served the state through war or politics. Anything that distracted from those tasks was suspect. The strength of this attitude shows up in great authors like Cicero and the historian Sallust, who still felt compelled to defend the value of literature in relation to one's public life and value.

Maturity is also a factor. A culture needs time to develop its own literature. There have to be enough people with a common language and culture, a shared appreciation of literary forms, and a sufficient level of literacy. The rapidly expanding Roman state did not assemble these until the third century

B

.

C

.

E

. The Romans were too busy conquering Italy, Greece, and Carthage to put things down on paper. Once they started, however, they made up for lost time. And although the Romans imitated the Greeks at the beginning, their literature quickly took on a stamp and character that, like everything else they did, were very much their own.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

Early Latin literature is characterized by two things: experimentation with and adaptation of Greek forms to the Latin language and the emergence of a Roman perspective. The first writers and educators of this period were Greeks from southern Italy, who were brought to Rome as slaves of conquest. Soon, however, the Greek literary forms of epic, comedy, tragedy, and history were in the hands of Latin authors, and philosophy and rhetoric began to develop a distinctive Roman approach.

B

.

C

.

E

.âDeath of Augustus in

C

.

E

. 14)

Turmoil marked the last century of the Republic. Civil unrest and civil wars erupted from a social and cultural system struggling to maintain control over its dominions and its own power. Amid the turmoil, Roman literature not only survived but seems to have risen to the challenge of its times (to fashion a more comprehensive role and identity for Rome and the Romans in the world) in a way that the Roman political system did not. Latin poetry, history, philosophy, and rhetoric were transformed by authors such as Catullus, Caesar, Lucretius, and Cicero. These authors synthesized Latin and Greek forms into a profound, powerful, and uniquely Roman literature. Their works are neither isolationist nor naively imitative in tone or technique but reveal a level of cultural confidence and sophistication in which authors master and combine elements of both Greek and Latin styles to their own satisfaction. This synthesis reached its zenith under Augustus. His reign ushered in a period of peace and stability that produced some of the West's finest literature from authors such as Virgil, Horace, Livy, and Ovid.

After a bumpy start in imperial succession under Tiberius and Gaius (Caligula), Latin literature entered a period distinguished particularly by the quantity of literature. The literature is wonderful for its quality as well, but against the likes of Virgil and Horace, this later phase is known as the Silver Age. Authors from this period include Petronius (novel), Lucan (epic), Martial (epigram), Tacitus (history), Suetonius (biography), and Juvenal (satire). Most of the modern popular images of Imperial Rome come from these authors.

The Silver Age was ended by another imperial succession crisis brought on by the death of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, who was himself an author of an influential work, the

Meditations.

The Literature of the Late Empire (ca 180â565)

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Robert Grave's popular book (and the PBS series)

I, Claudius

was developed from the work of the Roman author Tacitus (ca 56â117). Tacitus was an aristocratic Roman who served under the Roman emperors. He wrote dark and incriminating histories of the Imperial Age that show great insight into character and the effects of power. His writings, however, are also marred by his own biases.

During this period, Greco-Roman education and literacy was still strong. Latin literature, however, began to show the strains of both the west's decline and the turbulence of the struggles between Christian and pagan traditions. By the time the

Greco-Roman world had lost the upper hand, however, both eastern and western traditions had been indelibly stamped with its literature, rhetoric, and thought. One can see where sacred and secular combine to remarkable effect in the writings of St. Augustine of Hippo (354â430) and Boethius (480â524).

Meanwhile, literature in Greek, both sacred and secular, remained more viable in the eastern Empire and continued into the next millennium under the Byzantine umbrella.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

The Emperor Marcus Aurelius reflects the divergent cultural forces at work in the later Roman Empire. Born to wealthy Spanish parents in Rome, he was educated by, among others, the African rhetorician Fronto, the Greek rhetorician Herodes Atticus, and the Roman Junius Rusticus. Although a man of peace, as emperor he spent most of his time on the German and Parthian borders defending the Empire. It was during one of these campaigns that he wroteâin Greekâhis reflections on the Stoic principles he admired and tried to live by. These reflections, called “Things for himself” (

Ta eis heauton

), became known as the

Meditations

.

Well, you've accomplished a lot already in this odyssey through Roman history and civilization! Besides thinking about some of the different aspects of “Rome” that we'll be encountering, you've had a chance to look over a roadmap of Roman history and culture and learn a bit about some reasons for taking the trip. But before we hit the road, let's go to Chapter 2, “Rome FAQ: Hot Topics in Brief,” for some of the perennial highlights for Roman explorers like you.

- To understand how our world got to be as it is today, you have to know something about the Romans.

- Rome was a multicultural civilization that developed abstract concepts of civil and human rights and held a philosophically unusual view of time.

- “Rome” can mean many thingsâa city, a state, an empire, a religious center, a concept.

- Roman history divides primarily into the “Republic” and the “Empire,” with the “Principate” of Augustus providing the transition between the two.

- Roman literature developed long after Greek literature, and although it was highly influenced by the Greeks, it quickly took on a character of its own.