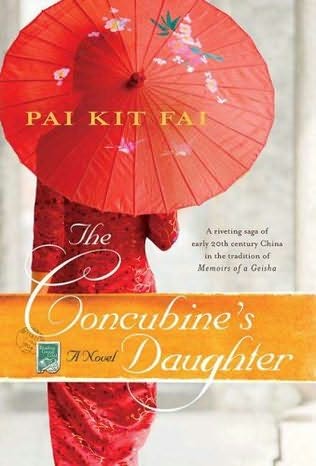

The Concubine's Daughter

Read The Concubine's Daughter Online

Authors: null

St. Martin’s Griffin

St. Martin’s Griffin New York

New YorkFai, Pai Kit, 1929–

The concubine’s daughter / Pai Kit Fai.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-312-35521-0

1. Women—China—Social conditions—Fiction. 2. China—Social life and customs—Fiction. I. Title.

PR 9619.3.P52 C66 2009

823’.914—dc22

When a book takes a while to finish, there’s a risk you might forget some of those who were with you at the start. First, it’s best to thank those who were beside you every step of the way: My wife, who has lived through a dozen books and never lost faith; an amazing editor, Hope Dellon, who put time and distance aside and shared the journey all the way, including the stony bits; Al Zuckerman, whose calm advice was constant and patience remarkable, and whose incomparable wisdom makes books out of stories and writers out of scribblers.

They would all have wasted their time if it weren’t for those brave souls who spoke nicely to my computer when I threatened to kill it: dear, reliable Christine Lenton was always there for a backup and Richard Harvey, a technical giant who was never too busy. A special thanks to my friends Master John Saw, Blake Powell, Bryce Courtenay, and Justin Milne, and they know why; Derek Goh for his unconditional generosity; and Marabel Caballes, who is as beautiful as her name and talked me through some computer glitches but never raised her voice.

So many friends who stopped by to make my day, not least that colossus of the Tasmanian bush, Bradley Trevor “Ironbark” Greive, whose mighty words in little books have put smiles upon 20 million faces and one to spare for me.

Great Pine Spice Farm on the Pearl River, Southern China, 1906

Y

ik-Munn, the farmer, poured

another cup of hot rice wine. His hand shook as though he too felt the agony endured behind the closed doors above. He had heard such commotion many times, and to him the shrieks of Number Four might just as well be the squeals of a sow advanced upon with a dull blade. Even in this small room, chosen for its isolation and quiet darkness, her bleating was an offense to his ears, following him like a demented wraith as he descended the stairs to seek a moment’s peace and privacy.

He supposed it was to be expected from the newest and youngest of his women and this, her firstborn. The first always came into the world with much caterwauling, but it opened the way for those yet to come—until they slid out as slickly as a calf from a cow. Still, in the year since he had fetched his concubine from the great northern city of Shanghai to Great Pine Farm—through the mouth of the Pearl River Delta and far into its fertile estuary—he had pondered the wisdom of his purchase on more than one occasion. He pondered it now.

Pai-Ling was barely fifteen when he bought her from a large family escaping the turmoil of Shanghai. The Ling clan had once been rich and powerful, occupying an extensive compound in the old quarter, well away from the foreign devil’s cantonments. After the Boxer Uprising, all face was lost; they were at the mercy of the tongs as extortion and kidnapping gripped the city in the name of the I-Ho-Chuan, or “Fists of Righ teousness.”

The Ling family had been left with no alternative but to return to the humble village of their birth. With their sons scattered, their belongings greatly reduced, they decided to sell the youngest daughter, the child of a favorite mistress and considered dispensable. Better that she be sold to an idiot farmer from the south than be kidnapped for a ransom they could not pay, to become a plaything for the Boxers or meet a miserable death in the hands of triad kidnappers.

Pai-Ling was taller in the way of northern women, more beautiful than the three wives who had serviced Yik-Munn’s long and arduous life but had become fat, and tiresome in his bed. She was proud, and her eyes were filled with unexpected dignity. Yik-Munn remembered well when she was first brought before him in the great reception hall of the Ling compound.

As he sat in his well-polished shoes and his best suit of bold check cloth, custom-made made for him in the Western style by a master tailor in Canton, she had glanced at his scanty hair, freshly trimmed and plastered with sweet-smelling pomade, without enthusiasm. His long, high-cheek-boned face shaved, patted, and pampered, even his large ears had been thoroughly reamed until they glowed. Their fleshy lobes were one of his finest features, said by the priests to be a sign of great wisdom, like those of the lord Buddha himself.

That all such careful preparation did not hide the deep-set eyes and hollow cheeks of an opium eater did not bother him. To afford the tears of the poppy whenever he wished was a sign of affluence among the farmers of Kwangtung Province. And to own such a suit, specially made to fit him alone and worn only by the big-city taipan, was proof that he was also a respected spice merchant.

Neither did the hostile look in her eyes discourage him. His only hesitation had been to learn that she had taught herself to read and write. This was unheard of along the banks of the Pearl and its many tributaries, at least among the families who had turned the fertile soils for many generations.

They were Hakka, the peasant clans of the south who knew of nothing but the moon’s rich harvests and the blessings of the Tu-Ti—the

earth gods—who watch over hardworking families with a benevolent eye. When she was not too heavy with child, a woman’s purpose was to plant and follow the plow, to harvest and grind, thresh and bale. Had not Number-One Wife continued to work on the rice terraces almost to the moment of birth after her third time—stopping only long enough to give him a healthy son, rest for the remainder of that day, and have the buffalo yoked to resume plowing as the sun rose the following morning?

Number Two had once made his heart trip like a boy’s with the appetite of a whore in the bedroom … but she was of no other use and had a whining voice that sawed its way into his soul. True, Number Three could read and write, and her fingertips were fast and light as a cricket as they tripped the beads of the abacus … but only to keep tally in the godown. One woman with brains was more than enough under Yik-Munn’s roof. An educated female would bring nothing but trouble to any clan.

Wives as sturdy and enduring as One and Two were worthy of their rice and of great value to a struggling farmer. Times were different now. The Great Pine spice farm had prospered; his elder sons were studying in the best schools, one of them running his own restaurant on the Golden Hill of Hong Kong. The younger ones still worked the spice fields, and his grandsons were already able to plant rice and gather a harvest.

So Pai-Ling was a plaything—perhaps to bear him more sons, but he expected nothing more of her and overlooked the unsettling discovery that she could not only read and write but was said to have studied the many faces of the moon and understood the passage of the star gods. This was the forbidden domain of priests and fortune-tellers; a girl child who sought such knowledge could be considered of unsound mind, liable to become rebellious and a danger to those around her. Still, the cost of Pai-Ling’s education had been borne by her family, and it was they who had allowed her to consult mischievous imps and pray to mysterious gods.