The Creation of Anne Boleyn (31 page)

Read The Creation of Anne Boleyn Online

Authors: Susan Bordo

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #England, #Historical Study & Educational Resources, #World, #Renaissance

When Henry and Anne finally sleep together, it is a wildly transporting experience for both of them: “I’m deep in love,” Anne declares (so deep she no longer cares about the divorce), and Henry proclaims it “a new age. Gold or some choicer metal—or no metal at all, but exaltation, darling. Wildfire in the air, wildfire in the blood!”

28

The irony (and existential essence and dramatic spine of the play) is that falling in love with Henry after years of hating him is the beginning of Anne’s downfall, for it finally releases him from his erotic bondage to her. “After that night,” she muses later in her room in the Tower, “I was lost.”

29

What follows is the speech that gave the play its title.

From the day he first made me his, to the last day I made him mine, yes, let me set it down in numbers. I who can count and reckon, and have the time. Of all the days I was his and did not love him—this; and this; and this many. Of all the days I was his—and he had ceased to love me—this many; and this. In days—it comes to a thousand days—out of the years. Strangely, just a thousand. And of that thousand—one—when we were both in love. Only one, when our loves met and overlapped and were both mine and his. When I no longer hated him, he began to hate me. Except for that one day. One day, out of all the years.

30

I’ve always loved that speech for its psychological acuity about the kind of love that is fueled by challenge and pursuit, as Henry’s desire for Anne was. Whatever her motives, Anne was not easily conquered. This may have inflamed Henry’s passion, but it also meant there was a danger to Anne in finally giving in. For what he found in his arms was a real woman rather than a fantasized ideal—and as a real woman, Anne, having been elevated in Henry’s imagination by years of longing, was bound to disappoint.

31

This is a new theme in Anne’s fictional afterlives, one which Norah Lofts develops in chilling detail after his and Anne’s first sex together. (It affects even Henry’s sense of smell.) “For years and years, whenever he had been near her he had been conscious of the scent of her hair, not oversweet, not musky, in no way obtrusive, a dry, clean fragrance, all her own; but now, nearer to her than he had ever been, he was only aware of his own freshly soaped odor and the scented oil which he had rubbed into his hair and beard . . . He could have cried when he thought of how he had soaked and scrubbed himself, put on his finest clothes and his jewels.”

32

All that for “just another woman in a bed!”

33

Anne and Henry’s sexual attraction for each other does not degenerate so starkly or decisively in

Anne of the Thousand Days.

Even after Henry has begun to court Jane, he still can be aroused by Anne; when her fury is ignited, so is his desire for her. And furious she often is—over his betrayal, over the prospect of Elizabeth’s being made a bastard, and over Henry’s underestimating of her integrity. No fictional Anne before had ever been so proudly defiant, so insistent on her own autonomy, so utterly unintimidated by Henry. For drama critic Joseph Wood Krutch, this is what made Anderson’s Anne so “intriguing.” “In her own way she is as ruthless as Henry, no dove snatched up by an eagle, but an eagle herself. What she has is a prideful integrity incapable of a sin against herself, though quite capable of most of the other sins in the calendar.”

34

This inability to “sin against herself” ultimately sends her to her death, but it’s also what gives her enormous power. She will risk anything, endure anything, in order to retain her self-respect. Even at the end, condemned to death, she continues to challenge Henry, tormenting him with a lie that is also a final show of her unwillingness to “do all this gently,” as Henry would like.

Before you go, perhaps you should hear one thing—I lied to you. I loved you, but I lied to you! I was untrue! Untrue with many!

35

She thus leaves Henry with an uncertainty that he will “take to the grave” (as she puts it).

36

Did she? Didn’t she? Unknowable and elusive once again, she goes to her death knowing that her own power in the relationship has been restored.

As successful as it was,

Anne of the Thousand Days

was not made into a movie until twenty years later. It was deemed untouchable by movie studios in 1949, as it dealt with subjects—adultery, incest, illegitimacy, even the word “virgin”—that the Motion Picture Production Code would not permit. It wasn’t until the sixties that the code began to be killed off, bit by bit, by the “foreign invasion” of sexually franker European films and the need for American movies to offer something that television could not. In 1966, Mike Nichols’s screen adaptation of Edward Albee’s

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?—

a less fatal but more foul-mouthed “bad romance” than

Anne of the Thousand Days—

did the code in. And Anderson’s Anne was ready to be revived—and, as I will argue, reimagined—for a new generation.

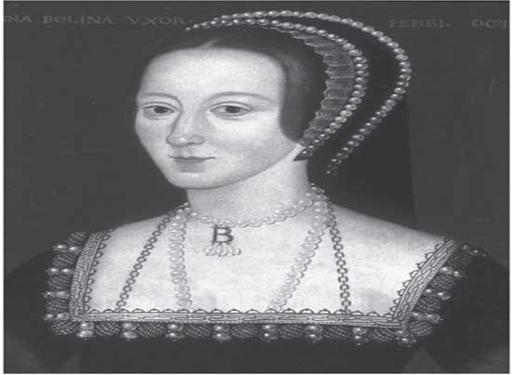

This sixteenth-century portrait (artist unknown), often referred to as “the NPG portrait” because it hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London, is thought to be one of the few surviving copies of an original painting. Although it’s not discernible in this black-and-white photograph of the portrait, Anne has chestnut—not black—hair.

© Heritage Images/Corbis

This anonymous portrait, hanging at Hever Castle, Anne’s childhood home, captures a childlike innocence not usually seen in depictions of Anne.

Hever Castle & Gardens

Anne in an Elizabethan collar. Depictions of Anne have often followed the fashions of the artist’s era, not Anne’s.

Alfredo Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY

In the nineteenth century, the early days of Henry’s relationship with Anne became a subject of romantic imagery, with Henry a tender suitor and Anne his adored (and blonde) darling.

Copyright and courtesy of Rotherham Heritage Services

A less idealizing nineteenth-century view of Henry that imagines a cold, unwavering Henry with a voluptuous, fainting Anne behaving according to Victorian stereotypes.

© Bettman/Corbis

Anne as tragic heroine. Early nineteenth-century French painters often drew on unjustly condemned historical figures, such as Anne and Lady Jane Grey, to comment on the politics of their own time.

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY