The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography (24 page)

Read The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography Online

Authors: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Tags: #Autobiography/Arts

For a month, the old celebrity came three times a week to my staff quarters, two meters wide by three meters long, where we rehearsed with great discipline. Canetti, for his part, told me a secret: “Chevalier is already passé. His success does not interest me; I believe it impossible. Instead, I know a great young musician, Michel Legrand: I’m going to take advantage of the show to launch him. I’m hiring a one-hundred-piece orchestra, something never seen before. It will be an absolute triumph. He’ll fill the Alhambra Theater. I’m asking you to accentuate his presence with your staging.”

I set up the hundred musicians on a wide staircase, forming a wall at the bottom, each wearing a suit of a different color in order to reproduce a painting by Paul Klee. Legrand was dressed in white. His arrangements of popular melodies were truly outstanding. But he, his hundred musicians, and the monumental sound of the instruments, were all overshadowed when the old man entered, dressed as a vagrant, with a red nose and a bottle of wine in hand, singing “Ma pomme.” It was a delirious success! So much so that the show, which had been expected to stay in theaters for a month, kept running for a year. The theater was renamed the Maurice Chevalier Alhambra. The singer rented an apartment across the street, so that every day he could look at the huge illuminated letters of his name.

From that moment on, I never ceased my theatrical and poetic activities. To relate everything I experienced during those years would be a subject for another book. Because Marceau’s sign holder had fallen ill he asked me, as a special favor, to replace him for the tour of Mexico. I did so. I fell in love with the country and stayed there, founding the Teatro de Vanguardia and putting on more than a hundred shows over the course of ten years. We worked with the greatest actresses and actors of the day; we premiered works by Strindberg, Samuel Beckett, Ionesco, Arrabal, Tardieu, Jarry, and Leonora Carrington, among many others, as well as the works of Mexican playwrights and my own works. We adapted Gogol, Nietzsche, Kafka, Wilhelm Reich, and a book by Eric Berne,

Games People Play,

which is still being performed today, thirty years later, and for which I had to assert myself, fight against censorship, and at one point even spend three days in jail. Some of my performances were shut down; at others, members of the extreme right wing stormed the theater, throwing bottles of acid. I had to flee in the dark, hidden in the back of a car, to avoid being lynched when my first film,

Fando y Lis,

premiered at the Acapulco Film Festival. Gradually, between successes, failures, scandals, and catastrophes, a profound moral crisis was demolishing the fanatical admiration I held for the theater. Theater, as a profession, is characterized by a display of those vices of character that people who are not artists do their absolute best to conceal. The egos of the actors are displayed in full view, without shame, without self-censorship, in their exaggerated narcissism. They are ambiguous, they are weak, they are heroic, they are traitors, they are faithful, they are stingy, they are generous. They fight for recognition; they want their name to be bigger than everyone else’s and to be at the top of the poster, over the title of the work. If they all earn the same salary, they demand that an envelope be slid into their pocket containing a few more dollars. They greet each other with great embraces but say horrible things about one another behind each other’s backs. They try desperately to get more lines; they steal the scene by stealthily calling attention to themselves. They are full of pride and vanity but also have no security in themselves, they want to be the center of attention, and they never stop competing, demanding to be seen, heard, and applauded at all times, even if they have to prostitute themselves in commercial advertisements. They only know how to talk about themselves, or about humanitarian problems such as a famine, epidemic, or genocide if they happen to be the lead promoters of some superficial solution. To increase their popularity they pass themselves off as devotees, tagging along with the pope or the Dalai Lama. All in all, they are adorable and disgusting, because they show in full daylight what their audience keeps hidden in darkness.

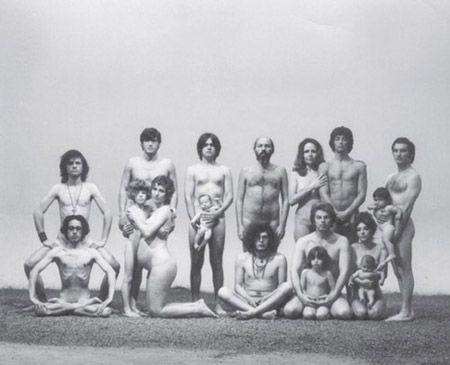

The cast of my theatrical work

Zaratustra

(Mexico, 1976). From left to right, back row: Henry West (musician); Héctor Bonilla (actor);Mickey Salas (musician), with his son; Carlos Áncira (actor); IselaVega (actress); Jorge Luque (actor); and Álvaro Carcaño (actor), with his son. Front row: Luis Urías (musician); Brontis Jodorowsky; Valérie Trumblay (in her womb, Teo Jodorowsky); El Greñas (seller of programs for the play); Alejandro Jodorowsky with Axel Cristóbal Jodorowsky; and Susana Camini (actress), with her son.

I wondered, Would it be possible for the theater to dispense with the actors? And, Why not the audience? The theater building seemed limited, useless, outdated. A show could be created anywhere, on a bus, in a cemetery, in a tree. It was useless to interpret a character. The person acting—not an actor—should not be putting on a spectacle to escape from himself, but to reestablish contact with the mystery within. The theater ceased to be a distraction and became an instrument of self-knowledge. I replaced the creation of written works with what I called the “ephemeral.”

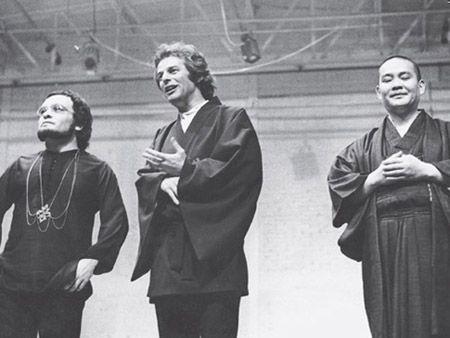

During the performance of

Zaratustra

in Mexico, with Fernando

Arrabal and the Zen master Ejo Takata. Photo: Hermanos Mayo.

During a performance an actor should completely melt into the “character,” fooling himself and others with such mastery as to misplace his own “person” and become another, a character with concise limits, made from sheer imagination. In the ephemeral, the acting person should eliminate the personality and attempt to be the person he is playing. In everyday life so-called normal people walk around in disguise, playing a character that has been inculcated by family, by society, or that they themselves have fabricated: a mask of pretense and bluster. The mission of the ephemeral was to make the individual cease to play a character in front of other characters, and ultimately to eliminate that character and suddenly become closer to the true person. This “other” who awakes amidst the euphoria of free action is not a puppet made of lies, but a being with minor limitations. The ephemeral act leads to the whole, to the release of higher forces, to a state of grace.

Without my realizing it, this exploration of the intimate mystery was the beginning of a therapeutic theater that ultimately led me to the creation of psychomagic. If I did not imagine this at the time, it was because I thought that what I was doing was a development of theatrical art. Before happenings began in the United States, I put on spectacles that could take place only once; I introduced perishable things like smoke, fruit, gelatin, the destruction of objects, baths of blood, explosions, burns, and so on. Once we performed in a place where two thousand chickens were clucking; another time we sawed through a double bass and two violins. I proceeded by searching for a place that someone would let me use, any sort of place, as long as it was not a theater: a painting academy, an asylum for the mentally ill, a hospital. Then I persuaded a group of people I knew, preferably not actors, to participate in a public presentation. Many people have an act in their soul that ordinary conditions do not allow them to carry out, but under favorable circumstances they rarely hesitate when offered the opportunity to express what sleeps within them. For me, an ephemeral had to be free to attend, like a party: when we staged them, we did not charge the guests for food or drinks. All the money I could save was invested in these presentations. I would ask the participant what he wanted to expose, then give him the means to do so. The painter Manuel Felguérez decided to slaughter a hen in front of the spectators and do an abstract painting on the spot using its guts, while at his side wearing a Nazi soldier’s uniform was his wife Lilia Carrillo, also a painter, who devoured a grilled chicken. A young actress who later became famous, Meche Carreño, wanted to dance naked to the sound of an African rhythm while a bearded man covered her body with shaving cream. Another woman wanted to appear as a classical dancer in a tutu without underwear and urinate while interpreting the death of a swan. An architecture student decided to appear with a mannequin and beat it violently, then pull several feet of linked sausages out from the crushed pubic area. One student came dressed as a university professor carrying a basket full of eggs and proceeded to smash one egg after another on his forehead while reciting algebraic formulas. Another, dressed as a cowboy, arrived with a large copper basin and several liters of milk. Lying in the container in a fetal position he recited an incestuous poem dedicated to his mother as he emptied the milk bottles, drinking the contents. A woman with long blond hair arrived walking on crutches and screaming at the top of her lungs, “My father is innocent, I am not!” At the same time she took pieces of raw meat from between her breasts and threw them at the audience. Then she sat down on a child’s chair and had her head shaved by a black barber. In front of her was a crib full of doll heads without eyes or hair. With her skull bare, she threw the heads at the audience, screaming, “It’s me!” A man dressed as a bridegroom pushed a bathtub full of blood onto the platform. A beautiful woman dressed as a bride followed him. He began to fondle her breasts, crotch, and legs, and finally, getting more and more excited, submerged her in the blood along with her ample white dress. He then rubbed her with a large octopus while she sang an aria from an opera. A woman with a great deal of red hair, pale skin, and a gold dress that clung close to her body appeared with a pair of shears in her hands. Several brown-skinned boys crept toward her, each one offering her a banana, which she sliced while laughing out loud.

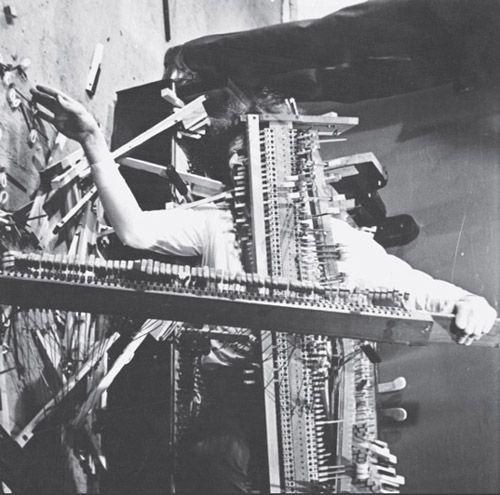

Smashing a piano on Mexican television, in 1969.