The Dangerous Book of Heroes (15 page)

Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

Cook reported the theft to Kalaniopu'u, who agreed to go with him to the

Resolution

until the cutter was returned. The king's young sons asked to go as well and, with their father's agreement, ran

ahead. On the beach they heard gunfire along the bay. Cook's men had fired to stop a canoe from leaving.

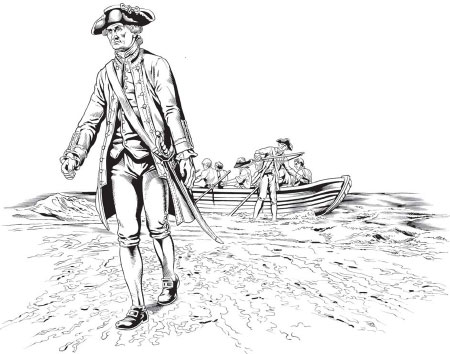

One of the king's wives wailed and begged him not to go. Two young chiefs took hold of the king's arms and sat him on the beach, while other islanders collected stones, spears, and clubs. The lieutenant of marines lined his men along the water's edge, their muskets loaded and ready. From the crowd someone cried that a chief had been killed in the firing along the bay. Cook understood what had been said and left the king sitting on the beach. He ordered the marines to return to the ships to avoid bloodshed and walked down the beach.

A warrior rushed at him wielding a stone and a dagger. Cook turned and in Polynesian ordered: “Put those things down!” but the man drew back his arm to throw the stone.

Cook fired his shotgun, using the barrel containing round shot, which would sting but not kill. The shot hit the warrior's coconut breastplate. He laughed and came on with his dagger raised. Cook fired the second barrel, containing ball, and the warrior fell to the beach.

There was a roar and the islanders attacked with stones and spears. The marines fired. Undeterred, the islanders

killed four marines before they could reload. The seamen in the boat came in to help, telling the king's sons to run for it before they were hurt. The boys ran away through the shallows.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Cook stood at the water's edge, a tall, commanding figure in navy-blue tailcoat and white breeches, facing the islanders. They paused. He turned to his seamen and marines with his hand held palm up to command a ceasefire. It was then, with his back to the islanders, that he was clubbed, stabbed, and killed. The marines and seamen fired their muskets into the mob and retreated to the boat. From the

Discovery,

the watching Clerke fired two ship's cannon overhead into the trees. Cook's body and the bodies of the four marines were torn apart as the boats rowed into deep water. It was over.

The next day, parts of Cook's body were returned to the

Resolution

by a sorrowful chief. Those remnantsâmissing his headâwere given a naval funeral to a captain's salute of ten guns.

Lieutenant Clerke took command of the

Resolution

and promoted Gore to command of the

Discovery.

The masts were repaired, and on a gray February day the two ships departed Owhyhee. Clerke continued as Cook had planned, exploring northwestward across the Pacific, but discovered nothing. The two ships sailed the cold northern sea into the Arctic, where Clerke found the ice farther south than the year before. There was no way through. Neither the Northwest nor the Northeast were viable passages. They are not still.

In the Arctic, Clerke died of tuberculosis. It was the worst weather for him, but he'd insisted on completing Cook's plans. Gore took command and turned south for the small Russian port of Petropavlovsk. There, Clerke was buried. The

Resolution

and the

Discovery

were repaired and departed for Britain. The passage home took a year. They arrived at London in October 1780, completing a voyage of four and a quarter years. Not one man in either ship had died of disease.

The chronometer in the

Resolution

was removed and supplied later to another ship bound for the South Seas named

Bounty.

It was removed from the

Bounty

at Pitcairn Island and is now in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

Mrs. Cook received a royal pension from King George, her

husband's share of the royalties of his published journals, and a specially struck gold medal from the Royal Society. She lived mostly alone until she died at age ninety-three. All six of their children died without heirs, the two eldest sons in service with the navy.

In Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States, and throughout the Pacific Islands there are memorials to Captain James Cook. In the United Kingdom there is a statue in the Mall near the Admiralty and one on the cliffs near Whitby. It's late, but not too late, for a significant memorial in London's Westminster Abbey or Saint Paul's to the greatest cartographer, surveyor, seaman, and navigator in history.

Recommended

Captain Cook: The Seaman's Seaman

by Alan Villiers

The Journals of Captain Cook,

edited by J. C. Beaglehole

The Life of Captain James Cook

by J. C. Beaglehole

The Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth, Hampshire, U.K.

The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

The Whitby Museum, Whitby, Yorkshire, U.K.

The Mitchell Library, Sydney, Australia

Endeavour

replica, Whitby, Yorkshire, U.K.

Endeavour

replica, Sydney, Australia

Captain Cook's Cottage, Melbourne, Australia

If you cannot understand that there is something in man which responds to the challenge of this mountain and goes out to meet it, that the struggle is the struggle of life itself, upward and forever upward, then you won't see why we go. What we get from this adventure is just sheer joy.

âGeorge Mallory

We look up. For weeks, for months, that is all we have done. Look up. And there it isâthe top of Everest. Only it is different now: so near, so close, only a little more than a thousand feet above us. It is no longer just a dream, a high dream in the sky, but a real and solid thing, a thing of rock and snow, that men can climb. We make ready. We will climb it. This time, with God's help, we will climb on to the end.

âTenzing Norgay

L

ess than sixty years ago, no one in the history of the world had conquered Everest. It is possible that George Mallory and Andrew Irvine made it in 1924, but they died in the attempt and there is no way to know if they were still climbing or coming down. Mallory's body was not even found until 1999.

The highest mountain in the world is still incredibly dangerous, and climbers die in the attempt every year. More than forty bodies remain frozen on the north side of the mountain, and others have been lost in avalanches, their whereabouts unknown.

Everest is part of the Himalayan range, on the border between Tibet and Nepal. In Tibet it is known as Chomolungma, or “Saint Mother,” while the Nepalese call it Sagarmatha, meaning “Goddess of the Sky.” Everest is named after George Everest, a British surveyor

in nineteenth-century India. Before World War II, ascents began in Tibet, but when China occupied and closed that country to foreigners, future attempts had to come from the Nepalese side.

Everest stands 29,035 feet highâa fraction under five and a half

miles

from sea level. For those who are interested in such things, the highest mountain from foot to tip is actually a Hawaiian island, though obviously, almost all of that is underwater.

Above 27,000 feet, the air is too thin to breathe without severe training and months of acclimatization. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay used bottled oxygen to make their ascent. Bad weather can make climbing impossible, which leaves only a small window each year when summit attempts can take place.

The British Everest expedition of 1953 came after years of expeditions to survey the approaches from Nepal. In 1951 a potential route to the top was noted, and in 1952 two Swiss attempts on the summit were made. The British team was in the Himalayas, training at high altitude and ready to climb if the Swiss failed. A French team was ready to go after them. At that time, nine of the eleven major attempts on the mountain had been British-sponsored. Such energy and risk is either impossible to explain or very simple. As George Mallory said when he was asked why he wanted to climb Everest: “Because it's there.”

The 1953 British expedition was led by John Hunt. It was a massive undertaking just to reach the area. More than three hundred porters were employed to bring ten thousand pounds of supplies and equipment. Twenty native Nepalese guides were engaged for the task, some of whom, like Tenzing Norgay, had climbed to 28,000 feet with the Swiss the previous year. As the expedition unpacked on the lawns of the British High Commission in Kathmandu, they discovered that they had forgotten the British flag to fly on the summit of Everest. Rather than go without it, the high commissioner gave them one from his official Rolls-Royce.

More than one climb had come within a thousand feet of the

summit but then been overwhelmed by exhaustion or blizzards. At that height, the mountain has already taken a fierce toll. All equipment, including oxygen bottles, has to be carried up, and progress is bitterly slow as the last reserves of strength and fitness dwindle away. As with breaking the four-minute mile, that last stretch seemed an impossible obstacle.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

By May 1953, the British team had crossed crevasses and climbed sheer ice and rock to set up Advance Base Camp at 21,000 feet. The region above that height is known as the “death zone,” as climbers can endure only a few days in some of the most hostile conditions on earth.

Two-men summit teams were considered to have the best chance. The first assault on the summit was by Charles Evans and Tom Bourdillon. They made it to within a few hundred feet of the top when their oxygen failed. Without warning, they were suddenly strangling in air too thin to breathe, and they had to return to the lower camp.

On May 28, an advance party went up to carry equipment to the highest camp possible. In that way, they could prepare the path for Hillary and Tenzing, who were the least exhausted pair. Hillary and Tenzing carried some fifty-six pounds of supplies up to what would be called Camp IXâabout halfway between Advance Base Camp and the summit. With three other menâAlfred Gregory, George Lowe, and Sherpa Ang Nyimaâthey rested as best they could. In a cramped tent, they slept for four hours and woke at dawn to find that the weather had cleared. The temperature was around -13°F (-25°C), which made windchill of the utmost importance. Winds on Everest regularly gusted up to eighty miles per hour and were a constant, deadly threat.

Both Hillary and Tenzing carried cylinders of oxygen and other equipment: fifty to sixty-three pounds for each man. The plan was for Gregory, Lowe, and Ang Nyima to go first and cut ice steps as high as they could, allowing Tenzing and Hillary to make a fast ascent and perhaps push on to the very top.

Hillary and Tenzing climbed quickly, joining the first party on a ridge at 27,900 feet. There they found the tattered remnant of the Swiss tent from where Tenzing himself had tried for the peak the year before. That experience would prove vital, as he was able to guide the team to the best route.

Their trail-breaking work done, Lowe, Gregory, and Ang turned back. After cutting steps in ice all day, they were exhausted, but they had given Hillary and Tenzing a chance to make the summit.

To preserve oxygen for the attempt, the two remaining men put away their breathing apparatus, gasping without it, to make a camp for the night. They pitched a tent, using only their weight to hold it in place. Tenzing made soup while Hillary checked the oxygen supplies. He had less than the ideal amount, but the first attempt by Bourdillon and Evans had abandoned oxygen cylinders even higher, and they hoped to find those and use them to get back down alive. Before they slept, Hillary and Tenzing ate sardines, tinned apricots, biscuits, honey, and jam, as well as drinking hot water with lemon crystals and sugar to ward off dehydration. Hillary found that his boots had frozen solid and had to cook them on a Primus stove to soften them.

Â

In the morning they hoisted the heavy oxygen tubes onto their shoulders. The day was bright and still, and they could see the South Summit ahead of them. Making good speed, they climbed a ridge toward it, locating the abandoned oxygen cylinders on the way. They passed the cut steps and reached the South Summit by 9

A.M

. on the twenty-ninth. A virgin ridge led onward, with a ten-thousand-foot drop along one edge. Hillary began to cut new steps in the snow, ascending in forty-foot stages. Eight thousand feet below them, they could see the Advance Base Camp as they climbed. At one point, Tenzing's oxygen

tubes froze solid and Hillary freed them when he saw the Sherpa growing weak. There was no margin for error of any kind.

They had to halt at a smooth forty-foot cliff of rock, still known today as the Hillary Step. Hillary said afterward that it would have been an interesting challenge to a group of expert climbers in England's Lake District, but at that height it seemed impassable. He found a place where he could wedge his body into a crack between the rock and solid snow and heaved himself up and onto a ledge at the top. Tenzing followed on the rope and began to cut steps once more as the ridge went on.

They pushed themselves to the limit of endurance and thought they had reached the top time and time again, only to find more to do. The “false summits” were heartbreaking. Slowly and painfully, they cut steps and trudged upward. At 11:30

A.M

. they stood on top of the world, the first men ever to stand on that spot. They thumped each other on the back and grinned.

Tenzing did not know how to work the camera, so Hillary took three pictures of him standing on the summit. He held an ice ax aloft, with the flags of the United Nations, Britain, Nepal, and India fluttering from it. Tenzing made an offering to the gods of the summit, burying a bar of chocolate and some biscuits. John Hunt had given Hillary a small crucifix to take to the top, and he placed it beside the other offerings. They also looked for traces of Mallory or Irving, as the bodies were still missing at that time, but saw no sign of them.

Exhausted as they were, they could not tarry for long, even for the best view on earth. They remained on the peak for just fifteen minutes before beginning the descent, moving as quickly as possible to reach the oxygen dump before their own supply ran out.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Hillary and Tenzing made it back to a lower camp and were greeted by George Lowe, carrying emergency oxygen and a hot lemon drink. They were too exhausted to say much, though Hillary managed: “Well, George, we knocked the bastard off.” The following day they climbed down to the Advance Base Camp and the rest of the team came out to see if they had been successful. George Lowe gave them the thumbs-up and waved his ice ax at the summit. The highest mountain on earth had been conquered at last. The job was done and Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay became famous around the world. The French team next in line to make the attempt were, frankly, gutted.

News reached England in time for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953. Her husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, had been the patron of the expedition, and the queen took a personal interest. Hillary was made a Knight Commander of the British Empire (KBE). In his twilight years, he was also made a member of the Order of the Garter, an honor completely in the queen's discretion. Only the reigning monarch, the Prince of Wales, and twenty-four “companions” hold the honor at any one time. Hillary returned to England on many occasions to attend the annual service in Saint George's Chapel, Windsor.

Tenzing Norgay was given the George Medal by Queen Elizabeth. He was honored by both India and Nepal and became director of the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling. He lived until 1986, dying at the age of seventy-one. His son climbed Everest in 1996.

Â

Edmund Hillary was just thirty-three when he stood on the peak of Everest. Though only two men made the summit, he always praised the teamwork that had made that final push possible. He also never revealed whether he or Tenzing had stepped onto the peak first. As far as Hillary was concerned, it just didn't matter. He went on to climb ten other peaks in the Himalayas and made a successful journey to the South Pole. Much of his later life he spent creating and working with the Himalayan Trust in Nepal. Nepalese people form the Gurkha regiments that have been Britain's allies for almost two

hundred years, and Hillary's trust built bridges, hospitals, airstrips, and almost thirty schools there.

He died on January 11, 2008, aged eighty-eight. In April of that year, Queen Elizabeth held a final service for him in Saint George's Chapel. Outside, Gurkha soldiers stood guard for the last time as the great man was honored and remembered.

Recommended

The Ascent of Everest

by John Hunt; includes the chapter

“The Summit” by Edmund Hillary