Read The Dangerous Book of Heroes Online

Authors: Conn Iggulden

The Dangerous Book of Heroes (52 page)

The blizzard eased, and the three broke camp and sledged north, still carrying Oates's sleeping bagâin case. On the seventeenth they were blizzard-bound. On the eighteenth they reached fifteen and a half miles from One Ton Depot, just three days away at their improved speed since Oates's leaving. They were eleven miles from One Ton on the nineteenth when another blizzard hit. By then, all of them had severe frostbite, Scott the worst by his own admission. On the twenty-first Wilson and Bowers planned to ski to One Ton and return with fuel and food, but the blizzard made it impossible. They lay inside the frozen tent, battered by the moaning wind.

Scott recorded: “22 and 23. Blizzard bad as everâWilson and Bowers unable to startâtomorrow last chanceâno fuel and only one or two of food leftâmust be near the end. Have decided it shall be naturalâwe shall march for the depot with or without our effects and die in our tracks.”

Atkinson and Patrick Keohane reached the barrier from Cape Evans on March 27, searching for their companions. They lasted thirty-five miles in the desperate conditions before turning back.

Scott's last entry was dated March 29. “Since the 21st we have had a continuous gale from W.S.W. and S.W. Every day we have been ready to start for our depot 11 miles away, but outside the door of the tent it remains a scene of whirling drift. I do not think we can hope for any better things now. We shall stick it out to the end, but we are getting weaker, of course, and the end cannot be far. It seems a pity, but I do not think I can write more. R. Scott.”

On November 12, a search party led by Atkinson including Gran,

Cherry-Garrard, Gerof, and his dogs reached them. Canadian Charles Wright first saw the tip of the tent poking above a snowdrift. They dug it out and looked inside.

It's probable that forty-three-year-old Scott died last, for the sleeping bags of Wilson and Bowers were tied from the outside, while Scott's was not. Scott's right arm was resting across Wilson, his great friend. Dr. Atkinson certified death from natural causes and recovered the opium and morphine. In their last letters, the three men's thoughts were not of themselves but of their families. Scott's final sentence reads “For God's sake look after our people.”

There are always “if onlys,” but what killed Scott, Wilson, Bowers and Oates was not “if onlys.” It was not because they failed to use dogs and ponies; they used them wherever they could. They also skied wherever they could. It was not because they failed to use accepted Antarctic practices; they established the accepted practices. It was not through missing depots, for they found them all. What killed them was the extraordinary weather.

Scott realized this and blamed no one except himself, for a leader is responsible for everything, even for events beyond his controlâas Amundsen and Shackleton are responsible for the deaths in their various expeditions. Scott wrote: “Subsidiary reasons for our failure to return are due to the sickness of different members of the party, but the real thing that has stopped us is the awful weather and unexpected cold towards the end of the journey. The traverse of

the Barrier has been quite three times as severe as any experience we had on the summit. There is no accounting for it, but the result has thrown out my calculations.”

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

There is an accounting for it now. From subsequent records and the calculations of meteorologists George Simpson of Britain and Susan Solomon of the United States, it is established that 1912 was a freak weather year.

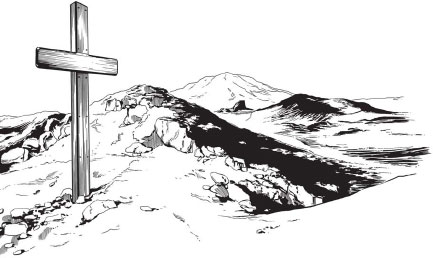

A cairn of snow was built over the tent and a cross of Tryggve Gran's skis erected on top. He wore Scott's skis back to Cape Evans to ensure that they traveled all the way. Above Hut Point, Scott's men erected a nine-foot-high wooden cross, the ice barrier behind. It's there today. On it is carved

IN MEMORIAM

, the five names, and the line

TO STRIVE, TO SEEK, TO FIND, AND NOT TO YIELD

.

It is the last line from Tennyson's poem “Ulysses.” They are apt because they are true: the five explorers strove, sought, found, and would not yield, even to circumstances beyond their control.

Evans sledged and skied until he collapsed, struggled forward on his knees until he was unconscious, and died never knowing where his strength had gone. Oates sledged and skied until he saw that his frostbite would slow and kill his comrades, so left to slow them no longer. Scott, Wilson, and Bowers pushed on until constant blizzards made further travel impossible, and died together naturally.

They did not yield.

Recommended

The Voyage of the

Discovery by Robert Falcon Scott, vols. 1 and 2

The Worst Journey in the World

by Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Diary of the “Terra Nova” Expedition 1910â12

by Dr. Edward Wilson

Scott's Last Expedition (personal journals)

by Robert Falcon Scott

The Coldest March: Scott's Fatal Antarctic Expedition

by Susan Solomon

Captain Scott

by Sir Ranulph Fiennes

T

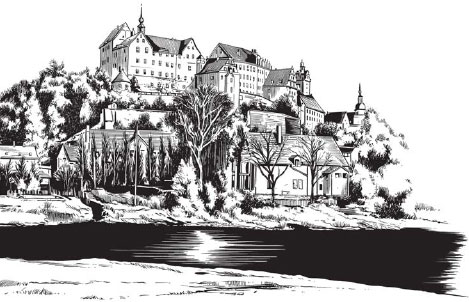

here were two qualifications for the Allied soldiers of World War II to be sent to Colditz Castle as prisoners. They had to be officers, and they had to have escaped before. Men who had tunneled out of other prisons, men who had walked out dressed as guards, laborers, and even women were sent to Colditz. In that way, the Germans managed to assemble a group of the most imaginative, determined, and experienced enemy officers in one place. In that context, it is perhaps not so surprising that when the prison was finally liberated by American soldiers in 1945, they found a fully working glider in the attic, ready to go.

The interned soldiers were all Allies, from Poland, Canada, Holland, France, Belgium, Britain, or, toward the end, the United States. However, there was always the chance that one might be a stool pigeon, a man planted by the Germans to spy on the prisoners. Security had to be tight, even among their own men. It is astonishing now to consider that the Colditz prisoners constructed realistic identity papers, uniforms, disguises, a typewriter, keys, and tunnel equipment from the few supplies they had or could steal. Their

beds were straw mattresses over boards that found use in shoring up tunnels, false doors, and cupboards and even as carved guns and glider wings. For tunnel lamps, they used candles made from cooking fat in a cigarette tin, with a pajama-cord wick.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

Colditz, known to the Germans as Oflag IV-C, had been used in World War I to hold prisoners and is about a thousand years old. One side overlooks a cliff above the Mulde River. To escape Colditz, situated in the heart of the German Reich, one had to cross four hundred miles of hostile territory in any direction. The walls were seven feet thick. But the first escape attempts involved Canadian officers just picking up buckets of whitewash and a long ladder and walking out, pretending to be painters. They were quickly recaptured, then kicked and battered with rifle butts. The stakes were always life and death for those who tried to escape, and despite the schoolboy quality of some of the attempts, it was never a game. In the “Great Escape” from Stalag Luft III in 1944, fifty out of the seventy-six escaping officers were caught and shot.

The garrison at Colditz always outnumbered the prisoners. The entire castle was floodlit at night, and as well as a hundred-foot drop on one side, there was a nine-foot barbed-wire fence, a moat, and a thirteen-foot-high outer wall. The Geneva Convention enforced the humane treatment of prisoners, at least in theory. German officers were interned in England, and there was a joint benefit in avoiding brutal treatment. Food and Red Cross parcels were allowed in at irregular intervals, and the prisoners could send carefully censored letters home. They could buy essential supplies, such as razor blades for shaving, toothpaste, soap, and even musical instruments. They were allowed to cook for themselves on small stoves in the dormitories.

The day began at 7:30

A.M

. and was organized into four roll calls in the main courtyard. At first the largest contingents were Polish and British. From those, there were a variety of talents available from the prison population, from lock pickers and forgers to civil engineers. There was a theater in the castle, and the prisoners put on elaborate productions and musicals while in Colditz. One of the

posters for a performance was replaced by the following: “For Sunshine Holidays, visit Sunny Colditz, Holiday Hotel. 500 beds, one bath. Cuisine by French chef. Large staff, always attentive and vigilant. Once visited, never left.”

Three times a week the prisoners were allowed exercise, from fencing to soccer and boxing. They were even allowed to keep a cat. When it vanished, the prisoners assumed it had gone to find a mate, until its body was discovered wrapped in a parcel in a trash bin. For all the surface gentility of their treatment, savagery was always close by. The last roll call was at 9

P.M

., at which point the “night shift” beganâthe escape committees of Colditz.

In January 1941, a British tunnel plan was put into action with the construction of a sliding box to go under floorboards. The theory was that even if the floorboards were taken up by investigating Germans, the rubble-filled box would look solid enough and hide the tunnel below. It passed inspection shortly after construction, and the guards saw nothing suspicious. However, the tunnel was abandoned as too easy to find. The men involved were locked into their room after some minor offense, and in protest, they unlocked and removed the door from its hinges, carried it around the camp in slow procession, and presented it to the German officers.

Pat Reid, MBE (later MC and author of

The Colditz Story

), spent part of a night in the Colditz brick drains, working to break through a wall. Taking turns with Rupert Barry and Dick Howe, he spent several nights scraping with bits of steel and nails. The underground bricks and cement proved tougher than their improvised tools. Another manhole entrance to the sewers looked more promising, and the men used the canteen as a base, having made a key for the door out of a piece of an iron bed. They made better progress but found the way blocked by thick clay. Reid's next idea was to make a vertical tunnel from the first, so that it would be possible to go some way from the buildings underground before heading for the outer wall.

On a surprise night inspection, the absence of the working tunnelers was discovered and the commandant told the men in the dormitory that they would all be shot. The Germans began tearing up the

floor and summoned dogs to search. The dogs found nothing, and Reid had to hang on to a manhole from underneath as guards tried to lift it. He and the others constructed a false wall in the tunnel, hiding their supplies behind it. After that, they returned in darkness to their beds. The Germans were astonished to have them reappear at morning roll call, and the commandant was criticized by his superiors for a false alarm.

After that, the Germans discovered the tunnel location suspiciously quickly, though they did not breach the false wall. The presence of a German spy, or stooge, in their midst had to be considered, and security grew tighter.

The camp population increased in 1941. Around 250 French officers arrived, then 60 Dutch and 2 Yugoslavs. In addition to those, the escape committees now included Irishmen, Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Jews, and an Indian doctor. They were united by a common enemy and had to keep one another informed so that one escape attempt did not ruin another.

Some of the British contingent found a guard who was amenable to a trade in contraband goods. They bribed him to look the other way for a crucial ten minutes of sentry duty. Eight Britons and four Poles prepared to use the still-undiscovered first tunnel they had dug in the drains. Cutting a square of earth from below, Reid was the first out into the courtyard, but a floodlight came on instantly. He was surrounded by armed Germansâtipped off by the guard they thought they had bribed to silence.

Other attempts followed. French laborers carried a British officer, Peter Allan, in a straw mattress being taken to soldiers' quarters in a local village. A fluent German-speaker, Allan made it to Vienna and even spent part of the journey with an SS officer who gave him a lift. In Vienna he was refused help by the American consulate, with the United States at that point not in the war. Exhaustion and starvation saw him taken to a local hospital, where he was arrested and sent back to Colditz for solitary confinement.

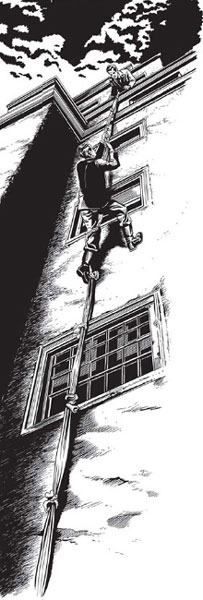

Around the same time, a French officer, Mairesse-Lebrun, made it to the local station before being apprehended. Mairesse-Lebrun was

an athletic and determined escaper, however. In July 1941, during his exercise period, he leaped the outer wire with the help of a friend who made his hands into a stirrup. Mairesse-Lebrun then climbed the wire from the outside and used it to get over the outer wall. He stole a local bicycle and cycled between sixty and a hundred miles a day, posing as an Italian officer. He avoided capture and crossed to Switzerland seven days after his escape. From there he made it to the Pyrenees before he was taken prisoner by the Fascist Spanish and broke his back jumping from a window. Crippled, Mairesse-Lebrun survived the war. His belongings in Colditz were later received at his French home in the parcel he had made and addressed before his escape.

Two Polish officers tried the perilous climb down the outer cliff but were discovered and captured by a German who heard the noise and opened a window right by their rope of tied sheets. In his excitement, he shouted for them to put their hands up, which they couldn't do without letting go of the rope.

Meanwhile, the British prisoners had begun another tunnel. They had homemade compasses, copied maps, rucksacks, and some rare German money, smuggled into the castle with new arrivals. They created civilian clothing by altering RAF uniforms. Twelve men were to escape, but that too failed when the Germans discovered them.

The Dutch contingent was more successful in 1941, managing to smuggle six men over the outer wall and wire in pairs on successive Sundays. Four out of six reached Switzerland safely. The other two were sent back to Colditz.

Winston Churchill's nephew Giles Romilly was sent to Colditz toward the end of 1941. He was closely guarded, though at one point he almost escaped, disguised as a French coal worker unloading supplies. Toward the end of the war, when Germany was losing badly, the

prominente,

or famous prisoners, were moved to a prison camp at Tittmoning, with the intention of using them as hostages. Romilly and two others escaped Tittmoning with the help of Dutchmen he had known in Colditz. One of the three was recaptured, but Romilly eventually made it back to England after the fall of Germany.

Copyright © 2009 by Graeme Neil Reid

By December 1941, the inhabitants of Colditz had managed to get hold of some yeast and began brewing beer from anything organic, sitting on the jars and bottles for hours on end to promote fermentation. After that, they created a still and made “firewater” that the Poles called vodka, of a sort. With Christmas on the way, they had quite a good collection of vintages.

As a trained engineer, Pat Reid had become the official “escape officer” for the British contingent. He noticed that the theater stage overlapped a floor below that led to the Germanguard house. He approached Airey Neave and J. Hyde-Thompson to take part in a new plan. Neave said that only the Dutch could make realistic German uniforms, so two Dutch officers were brought in for the attempt. They made uniform buttons, eagles, and swastikas by pouring molten lead into intricately carved molds, then attached them to adapted Dutch greatcoats, which were similar to the German ones. Leather belts and holsters were cut from linoleum, and they carried well-forged German identity documents.

Reid and a Canadian, Hank Wardle, cut through the ceiling of the room under the stage, camouflaging and repainting a removable hatch with great care. They were experienced lock pickers, and the doors beyond gave them no trouble. It went like a charm. Neave and the Dutchman Tony Luteyn went first, with Hyde-Thompson and the second Dutchman following the next night. As escape officer, Reid could not go himselfâhis skills were too valuable. The Germans discovered that they were missing four men and began to search the castle.

Neave and Luteyn crossed to Switzerland, making Neave the first Briton to escape from Colditz successfully. He went on to become a Conservative MP in 1953 and

later served as a minister in Margaret Thatcher's opposition government. Tragically, after surviving so many perils, he was killed in a car bomb planted by Irish Republicans a few months before the 1979 election. His book describing the Colditz escape,

They Have Their Exits,

is a great read. Hyde-Thompson and his companion were caught and returned to Colditz.

The Germans discovered the stage hatch with the help of a Polish informer whom they controlled by blackmail. The Poles discovered his identity, and their senior officer gave the commandant a day to remove him before they hanged him themselves.

As 1942 crept by, the French contingent worked on a tunnel that had its entrance in the clock tower. They also sent out one Lieutenant

Boulé, dressed as a beautiful blond woman. The disguise was discovered when “she” dropped her watch and a guard returned it. The Dutch tried one large man sitting on the grass, hiding a smaller man beneath his coat while he dug a shallow grave. Dogs found him before he was missed.