The Dark Tower IV Wizard and Glass (52 page)

Read The Dark Tower IV Wizard and Glass Online

Authors: Stephen King

“Good even, sai Thorin,” Pettie said. And before Coral could so much as open her mouth, the whore had put a shot glass on the bar and filled it full of whiskey. Coral looked at it with dismay. Did they all know, then?

“I don’t want that,” she snapped. “Why in Eld’s name would I? Sun isn’t even down! Pour it back into the bottle, for yer father’s sake, and then get the hell out of here. Who d’ye think yer serving at five o’ the clock, anyway? Ghosts?”

Pettie’s face fell a foot; the heavy coat of her makeup actually seemed to crack apart. She took the funnel from under the bar, stuck it in the neck of the bottle, and poured the shot of whiskey back in. Some went onto the bar in spite of the funnel; her plump hands (now ringless; her rings had been traded for food at the mercantile across the street long since) were shaking. “I’m sorry, sai. So I am. I was only—”

“I don’t care what ye was only,” Coral said, then turned a bloodshot eye on Sheb, who had been sitting on his piano-bench and leafing through old sheet-music. Now he was staring toward the bar with his mouth hung open. “And what are

you

looking at, ye frog?”

“Nothing, sai Thorin. I—”

“Then go look at it somewhere else. Take this pig with’ee. Give her a bounce, why don’t ye? It’ll be good for her skin. It might even be good for yer own.”

“I—”

“Get out! Are ye deaf? Both of ye!”

Pettie and Sheb went away toward the kitchen instead of the cribs upstairs, but it was all the same to Coral. They could go to hell as far as she was concerned. Anywhere, as long as they were out of her aching face.

She went behind the bar and looked around. Two men playing cards over in the far corner. That hardcase Reynolds was watching them and sipping a beer. There was another man at the far end of the bar, but he was staring off into space, lost in his own world. No one was paying any especial attention to

sai Coral Thorin, and what did it matter if they were? If Pettie knew, they all knew.

She ran her finger through the puddle of whiskey on the bar, sucked it, ran it through again, sucked it again. She grasped the bottle, but before she could pour, a spidery monstrosity with gray-green eyes leaped, hissing, onto the bar. Coral shrieked and stepped back, dropping the whiskey bottle between her feet . . . where, for a wonder, it didn’t break. For a moment she thought her head would break, instead—that her swelling, throbbing brain would simply split her skull like a rotten eggshell. There was a crash as the card-players overturned their table getting up. Reynolds had drawn his gun.

“Nay,” she said in a quavering voice she could hardly recognize. Her eyeballs were pulsing and her heart was racing. People

could

die of fright, she realized that now. “Nay, gentlemen, all’s well.”

The six-legged freak standing on the bar opened its mouth, bared its needle fangs, and hissed again.

Coral bent down (and as her head passed below the level of her waist, she was once more sure it was going to explode), picked up the bottle, saw that it was still a quarter full, and drank directly from the neck, no longer caring who saw her do it or what they thought.

As if hearing her thought, Musty hissed again. He was wearing a red collar this afternoon—on him it looked baleful rather than jaunty. Beneath it was tucked a white scrap of paper.

“Want me to shoot it?” a voice drawled. “I will if you like. One slug and won’t be nothing left but claws.” It was Jonas, standing just inside the batwings, and although he looked not a whole lot better than she felt, Coral had no doubt he could do it.

“Nay. The old bitch’ll turn us all into locusts, or something like, if ye kill her familiar.”

“What bitch?” Jonas asked, crossing the room.

“Rhea Dubativo. Rhea of the Cöos, she’s called.”

“Ah! Not the bitch but the witch.”

“She’s both.”

Jonas stroked the cat’s back. It allowed itself to be petted, even arching against his hand, but he only gave it the single caress. Its fur had an unpleasant damp feel.

“Would you consider sharing that?” he asked, nodding

toward the bottle. “It’s early, but my leg hurts like a devil sick of sin.”

“Your leg, my head, early or late. On the house.”

Jonas raised his white eyebrows.

“Count yer blessings and have at it, cully.”

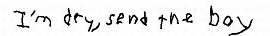

She reached toward Musty. He hissed again, but allowed her to draw the note out from under his collar. She opened it and read the five words that were printed there:

“Might I see?” Jonas asked. With the first drink down and warming his belly, the world looked better.

“Why not?” She handed him the note. Jonas looked, then handed it back. He had almost forgotten Rhea, and that wouldn’t have done at all. Ah, but it was hard to remember everything, wasn’t it? Just lately Jonas felt less like a hired gun than a cook trying to make all nine courses of a state dinner come out at the same time. Luckily, the old hag had reminded him of her presence herself. Gods bless her thirst. And his own, since it had landed him here at the right time.

“Sheemie!” Coral bawled. She could also feel the whiskey working; she felt almost human again. She even wondered if Eldred Jonas might be interested in a dirty evening with the Mayor’s sister . . . who knew what might speed the hours?

Sheemie came in through the batwings, hands grimy, pink

sombrera

bouncing on his back at the end of its

cuerda

. “Aye, Coral Thorin! Here I be!”

She looked past him, calculating the sky. Not tonight, not even for Rhea; she wouldn’t send Sheemie up there after dark, and that was the end of it.

“Nothing,” she said in a voice that was gentler than usual. “Go back to yer flowers, and see that ye cover them well. It bids frosty.”

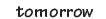

She turned over Rhea’s note and scrawled a single word on it:

This she folded and handed to Jonas. “Stick it under that stink’s collar for me, will ye? I don’t want to touch him.”

Jonas did as he was asked. The cat favored them with a

final wild green look, then leaped from the bar and vanished beneath the batwings.

“Time is short,” Coral said. She hadn’t the slightest idea what she meant, but Jonas nodded in what appeared to be perfect understanding. “Would you care to go upstairs with a closet drunk? I’m not much in the looks department, but I can still spread em all the way to the edge of the bed, and I don’t just lie there.”

He considered, then nodded. His eyes were gleaming. This one was as thin as Cordelia Delgado . . . but what a difference, eh? What a difference! “All right.”

“I’ve been known to say some nasty things—fair warning.”

“Dear lady, I shall be all ears.”

She smiled. Her headache was gone. “Aye. I’ll just bet ye will.”

“Give me a minute. Don’t move a step.” He walked across to where Reynolds sat.

“Drag up a chair, Eldred.”

“I think not. There’s a lady waiting.”

Reynolds’s gaze flicked briefly toward the bar. “You’re joking.”

“I never joke about women, Clay. Now mark me.”

Reynolds sat forward, eyes intent. Jonas was grateful this wasn’t Depape. Roy would do what you asked, and usually well enough, but only after you’d explained it to him half a dozen times.

“Go to Lengyll,” he said. “Tell him we want to put about a dozen men—no less than ten—out at yon oilpatch. Good men who can get their heads down and keep them down and not snap the trap too soon on an ambush, if ambushing’s required. Tell him Brian Hookey’s to be in charge. He’s got a level head, which is more than can be said for most of these poor things.”

Reynolds’s eyes were hot and happy. “You expect the brats?”

“They’ve been out there once, mayhap they’ll be out again. If so, they’re to be crossfired and knocked down dead. At once and with no warning. You understand?”

“Yar! And the tale after?”

“Why, that the oil and the tankers must have been their business,” Jonas said with a crooked smile. “To be taken to Farson, at their command and by confederates unknown. We’ll

be carried through the streets on the town’s shoulders, come Reap. Hailed as the men who rooted out the traitors. Where’s Roy?”

“Gone back to Hanging Rock. I saw him at noon. He says they’re coming, Eldred; says when the wind swings into the east, he can hear approaching horse.”

“Maybe he only hears what he wants to hear.” But he suspected Depape was right. Jonas’s mood, at rock bottom when he stepped into the Travellers’ Rest, was now very much on the rebound.

“We’ll start moving the tankers soon, whether the brats come or not. At night, and two by two, like the animals going on board Old Pa’s Ark.” He laughed at this. “But we’ll leave some, eh? Like cheese in a trap.”

“Suppose the mice don’t come?”

Jonas shrugged. “If not one way, another. I intend to press them a little more tomorrow. I want them angry, and I want them confused. Now go on about your business. I have yon lady waiting.”

“Better you than me, Eldred.”

Jonas nodded. He guessed that half an hour from now, he would have forgotten all about his aching leg. “That’s right,” he said. “You she’d eat like fudge.”

He walked back to the bar, where Coral stood with her arms folded. Now she unfolded them and took his hands. The right she put on her left breast. The nipple was hard and erect under his fingers. The forefinger of his left hand she put in her mouth, and bit down lightly.

“Shall we bring the bottle?” Jonas asked.

“Why not?” said Coral Thorin.

If she’d gone to sleep as drunk as had been her habit over the last few months, the creak of the bedsprings wouldn’t have awakened her—a bomb-blast wouldn’t have awakened her. But although they’d brought the bottle, it still stood on the night-table of the bedroom she maintained at the Rest (it was as big as any three of the whores’ cribs put together), the level of the whiskey unchanged. She felt sore all over her body, but her head was clear; sex was good for that much, anyway.

Jonas was at the window, looking out at the first gray traces

of daylight and pulling his pants up. His bare back was covered with crisscrossed scars. She thought to ask him who had administered such a savage flogging and how he’d survived it, then decided she’d do better to keep quiet.

“Where are ye off to?” she asked.

“I believe I’m going to start by finding some paint—any shade will do—and a street-mutt still in possession of its tail. After that, sai, I don’t think you want to know.”

“Very well.” She lay down and pulled the covers up to her chin. She felt she could sleep for a week.

Jonas yanked on his boots and went to the door, buckling his gunbelt. He paused with his hand on the knob. She looked at him, grayish eyes already half-filled with sleep again.

“I’ve never had better,” Jonas said.

Coral smiled. “No, cully,” she said. “Nor I.”

R

OLAND AND

C

UTHBERT

1

Roland, Cuthbert, and Alain came out onto the porch of the Bar K bunkhouse almost two hours after Jonas had left Coral’s room at the Travellers’ Rest. By then the sun was well up over the horizon. They weren’t late risers by nature, but as Cuthbert put it, “We have a certain In-World image to maintain. Not laziness but

lounginess.

”

Roland stretched, arms spread toward the sky in a wide

Y

, then bent and grasped the toes of his boots. This caused his back to crackle.

“I hate that noise,” Alain said. He sounded morose and sleepy. In fact, he had been troubled by odd dreams and premonitions all night—things which, of the three of them, only he was prey to. Because of the touch, perhaps—with him it had always been strong.

“That’s why he does it,” Cuthbert said, then clapped Alain on the shoulder. “Cheer up, old boy. You’re too handsome to be downhearted.”

Roland straightened, and they walked across the dusty yard toward the stables. Halfway there, he came to a stop so sudden that Alain almost ran into his back. Roland was looking east. “Oh,” he said in a funny, bemused voice. He even smiled a little.

“Oh?” Cuthbert echoed. “Oh what, great leader? Oh joy, I shall see the perfumed lady anon, or oh rats, I must work with my smelly male companions all the livelong day?”

Alain looked down at his boots, new and uncomfortable when they had left Gilead, now sprung, trailworn, a little

down at the heels, and as comfortable as workboots ever got. Looking at them was better than looking at his friends, for the time being. There was always an edge to Cuthbert’s teasing these days; the old sense of fun had been replaced by something that was mean and unpleasant. Alain kept expecting Roland to flash up at one of Cuthbert’s jibes, like steel that has been struck by sharp flint, and knock Bert sprawling. In a way, Alain almost wished for it. It might clear the air.

But not the air of this morning.

“Just oh,” Roland said mildly, and walked on.

“Cry your pardon, for I know you’ll not want to hear it, but I’d speak a further word about the pigeons,” Cuthbert said as they saddled their mounts. “I still believe that a message—”

“I’ll make you a promise,” Roland said, smiling.

Cuthbert looked at him with some mistrust. “Aye?”

“If you still want to send by flight tomorrow morning, we’ll do so. The one you choose shall be sent west to Gilead with a message of your devising banded to its leg. What do you say, Arthur Heath? Is it fair?”

Cuthbert looked at him for a moment with a suspicion that hurt Alain’s heart. Then he also smiled. “Fair,” he said. “Thank you.”

And then Roland said something which struck Alain as odd and made that prescient part of him quiver with disquiet. “Don’t thank me yet.”

“I don’t want to go up there, sai Thorin,” Sheemie said. An unusual expression had creased his normally smooth face—a troubled and fearful frown. “She’s a scary lady. Scary as a beary, she is. Got a wart on her nose, right here.” He thumbed the tip of his own nose, which was small and smooth and well molded.

Coral, who might have bitten his head off for such hesitation only yesterday, was unusually patient today. “So true,” she said. “But Sheemie, she asked for ye special, and she tips. Ye know she does, and well.”

“Won’t help if she turns me into a beetle,” Sheemie said morosely. “Beetles can’t spend coppers.”

Nevertheless, he let himself be led to where Caprichoso, the inn’s pack-mule, was tied. Barkie had loaded two small

tuns over the mule’s back. One, filled with sand, was just there for balance. The other held a fresh pressing of the

graf

Rhea had a taste for.

“Fair-Day’s coming,” Coral said brightly. “Why, it’s not three weeks now.”

“Aye.” Sheemie looked happier at this. He loved Fair-Days passionately—the lights, the firecrackers, the dancing, the games, the laughter. When Fair-Day came, everyone was happy and no one spoke mean.

“A young man with coppers in his pocket is sure to have a good time at the Fair,” Coral said.

“That’s true, sai Thorin.” Sheemie looked like someone who has just discovered one of life’s great principles. “Aye, truey-true, so it is.”

Coral put Caprichoso’s rope halter into Sheemie’s palm and closed the fingers over it. “Have a nice trip, lad. Be polite to the old crow, bow yer best bow . . . and make sure ye’re back down the hill before dark.”

“Long before, aye,” Sheemie said, shivering at the very thought of still being up in the Cöos after nightfall. “Long before, sure as loaves ’n fishes.”

“Good lad.” Coral watched him off, his pink

sombrera

now clapped on his head, leading the grumpy old pack-mule by its rope. And, as he disappeared over the brow of the first mild hill, she said it again: “Good lad.”

Jonas waited on the flank of a ridge, belly-down in the tall grass, until the brats were an hour gone from the Bar K. He then rode to the ridgetop and picked them out, three dots four miles away on the brown slope. Off to do their daily duty. No sign they suspected anything. They were smarter than he had at first given them credit for . . . but nowhere near as smart as they thought they were.

He rode to within a quarter mile of the Bar K—except for the bunkhouse and stable, a burned-out hulk in the bright sunlight of this early autumn day—and tethered his horse in a copse of cottonwoods that grew around the ranch house spring. Here the boys had left some washing to dry. Jonas stripped the pants and shirts off the low branches upon which

they had been hung, made a pile of them, pissed on them, and then went back to his horse.

The animal stamped the ground emphatically when Jonas pulled the dog’s tail from one of his saddlebags, as if saying he was glad to be rid of it. Jonas would be glad to be rid of it, too. It had begun giving off an unmistakable aroma. From the other saddlebag he took a small glass jar of red paint, and a brush. These he had obtained from Brian Hookey’s eldest son, who was minding the livery stable today. Sai Hookey himself would be out to Citgo by now, no doubt.

Jonas walked to the bunkhouse with no effort at concealment . . . not that there was much in the way of concealment to be had out here. And no one to hide from, anyway, now that the boys were gone.

One of them had left an actual book—Mercer’s

Homilies and Meditations

—on the seat of a rocking chair on the porch. Books were things of exquisite rarity in Mid-World, especially as one travelled out from the center. This was the first one, except for the few kept in Seafront, that Jonas had seen since coming to Mejis. He opened it. In a firm woman’s hand he read:

To my dearest son, from his loving MOTHER.

Jonas tore this page out, opened his jar of paint, and dipped the tips of his last two fingers inside. He blotted out the word MOTHER with the pad of his third finger, then, using the nail of his pinky as a makeshift pen, printed CUNT above MOTHER. He poked this sheet on a rusty nailhead where it was sure to be seen, then tore the book up and stamped on the pieces. Which boy had it belonged to? He hoped it was Dearborn’s, but it didn’t really matter.

The first thing Jonas noticed when he went inside was the pigeons, cooing in their cages. He had thought they might be using a helio to send their messages, but pigeons! My! That was ever so much more trig!

“I’ll get to you in a few minutes,” he said. “Be patient, darlings; peck and shit while you still can.”

He looked around with some curiosity, the soft coo of the pigeons soothing in his ears. Lads or lords? Roy had asked the old man in Ritzy. The old man had said maybe both. Neat lads, at the very least, from the way they kept their quarters, Jonas thought. Well trained. Three bunks, all made. Three piles of goods at the foot of each, stacked up just as neat. In

each pile he found a picture of a mother—oh, such good fellows they were—and in one he found a picture of both parents. He had hoped for names, possibly documents of some kind (even love letters from the girl, mayhap), but there was nothing like that. Lads or lords, they were careful enough. Jonas removed the pictures from their frames and shredded them. The goods he scattered to all points of the compass, destroying as much as he could in the limited time he had. When he found a linen handkerchief in the pocket of a pair of dress pants, he blew his nose on it and then spread it carefully on the toes of the boy’s dress boots, so that the green splat would show to good advantage. What could be more aggravating—more

unsettling

—than to come home after a hard day spent tallying stock and find some stranger’s snot on one of your personals?

The pigeons were upset now; they were incapable of scolding like jays or rooks, but they tried to flutter away from him when he opened their cages. It did no good, of course. He caught them one by one and twisted their heads off. That much accomplished, Jonas popped one bird beneath the strawtick pillow of each boy.

Beneath one of these pillows he found a small bonus: paper strips and a storage-pen, undoubtedly kept for the composition of messages. He broke the pen and flung it across the room. The strips he put in his own pocket. Paper always came in handy.

With the pigeons seen to, he could hear better. He began walking slowly back and forth on the board floor, head cocked, listening.

When Alain came riding up to him at a gallop, Roland ignored the boy’s strained white face and burning, frightened eyes. “I make it thirty-one on my side,” he said, “all with the Barony brand, crown and shield. You?”

“We have to go back,” Alain said. “Something’s wrong. It’s the touch. I’ve never felt it so clear.”

“Your count?” Roland asked again. There were times, such as now, when he found Alain’s ability to use the touch more annoying than helpful.

“Forty. Or forty-one, I forget. And what does it matter?

They’ve moved what they don’t want us to count. Roland, didn’t you hear me? We have to go back! Something’s wrong!

Something’s wrong at our place!

”

Roland glanced toward Bert, riding peaceably some five hundred yards away. Then he looked back at Alain, his eyebrows raised in a silent question.

“Bert? He’s numb to the touch and always has been—you know it. I’m not. You know I’m not! Roland, please! Whoever it is will see the pigeons! Maybe find our

guns

!” The normally phlegmatic Alain was nearly crying in his excitement and dismay. “If you won’t go back with me, give me leave to go back by myself! Give me leave, Roland, for your father’s sake!”

“For

your

father’s sake, I give you none,” Roland said. “My count is thirty-one. Yours is forty. Yes, we’ll say forty. Forty’s a good number—good as any, I wot. Now we’ll change sides and count again.”

“What’s wrong with you?” Alain almost whispered. He was looking at Roland as if Roland had gone mad.

“Nothing.”

“You

knew

! You knew when we left this morning!”

“Oh, I might have seen something,” Roland said. “A reflection, perhaps, but . . . do you trust me, Al? That’s what matters, I think. Do you trust me, or do you think I lost my wits when I lost my heart? As he does?” He jerked his head in Cuthbert’s direction. Roland was looking at Alain with a faint smile on his lips, but his eyes were ruthless and distant—it was Roland’s over-the-horizon look. Alain wondered if Susan Delgado had seen that expression yet, and if she had, what she made of it.

“I trust you.” By now Alain was so confused that he didn’t know for sure if that was a lie or the truth.

“Good. Then switch sides with me. My count is thirty-one, mind.”

“Thirty-one,” Alain agreed. He raised his hands, then dropped them back to his thighs with a slap so sharp his normally stolid mount laid his ears back and jigged a bit under him. “Thirty-one.”

“I think we may go back early today, if that’s any satisfaction to you,” Roland said, and rode away. Alain watched him. He’d always wondered what went on in Roland’s head, but never more than now.

Creak. Creak-creak.

Here was what he’d been listening for, and just as Jonas was about to give up the hunt. He had expected to find their hidey-hole a little closer to their beds, but they were trig, all right.

He went to one knee and used the blade of his knife to pry up the board which had creaked. Under it were three bundles, each swaddled in dark strips of cotton cloth. These strips were damp to the touch and smelled fragrantly of gun-oil. Jonas took the bundles out and unwrapped each, curious to see what sort of calibers the youngsters had brought. The answer turned out to be serviceable but undistinguished. Two of the bundles contained single five-shot revolvers of a type then called (for no reason I know) “carvers.” The third contained two guns, six-shooters of higher quality than the carvers. In fact, for one heart-stopping moment, Jonas thought he had found the big revolvers of a gunslinger—true-blue steel barrels, sandalwood grips, bores like mineshafts. Such guns he could not have left, no matter what the cost to his plans. Seeing the plain grips was thus something of a relief. Disappointment was never a thing you looked for, but it had a wonderful way of clearing the mind.

He rewrapped the guns and put them back, put the board back as well. A gang of ne’er-do-well clots from town might possibly come out here, and might possibly vandalize the unguarded bunkhouse, scattering what they didn’t tear up, but find a hiding place such as this? No, my son. Not likely.

Do you really think they’ll believe it was hooligans from town that did this?

They might; just because he had underestimated them to start with didn’t mean he should turn about-face and begin overestimating them now. And he had the luxury of not needing to care. Either way, it would make them angry. Angry enough to rush full-tilt around their Hillock, perhaps. To throw caution to the wind . . . and reap the whirlwind.

Jonas poked the end of the severed dog’s tail into one of the pigeon-cages, so it stuck up like a huge, mocking feather. He used the paint to write such charmingly boyish slogans as