The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland (21 page)

Read The Day the World Came to Town: 9/11 in Gander, Newfoundland Online

Authors: Jim Defede

Tags: #Canada, #History, #General

The flight to Dublin was uneventful. Between the steady stream of phone calls from the O’Rourke family and a few pointed inquiries from Hillary Clinton’s office, Aer Lingus officials were not going to take any chances with Hannah and Dennis O’Rourke. When their plane landed in Dublin at 2:30

A.M.

, they were met by four agents for the airline, who escorted them through the airport and guaranteed them they would be on the next possible flight to New York.

Hannah’s brothers and sisters in Ireland also met the plane. Only a few days before they had all been together under happier circumstances. Hannah had had no idea she would see them again so soon, and the reason crippled her with anguish. Not even the sight of her siblings could allay her fears. The next available plane to New York was set to leave in ten hours. She still wondered if her family on Long Island was hiding the truth from her. Did they already know Kevin was dead? Had they found his body? Were they waiting to tell her in person? Ten more hours and another plane trip across the ocean and she would be home, and then she’d know the answer.

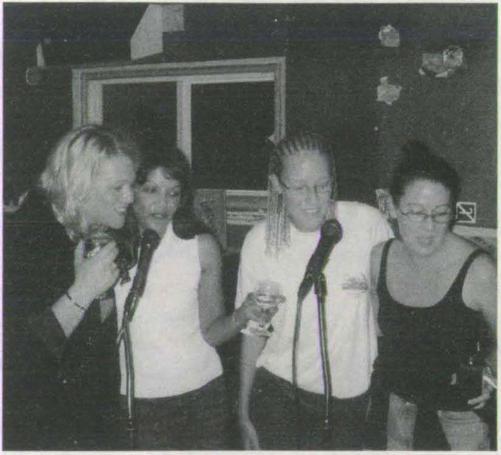

Karaoke at the Trailways Pub.

Courtesy of Lana Etherington

T

he most infamous of Newfoundland traditions is the “Screeching-In” ceremony, which allows a visitor to become an honorary Newfie through a series of challenges that test the strength of person’s stomach, the deftness of his or her tongue, and his or her ability to drink an unhealthy amount of alcohol. Not just any alcohol. One must drink a brand of liquor unique to Newfoundland. A lowbrow rum known affectionately as Screech.

The history of Screech has long been debated in Newfoundland. In the 1970s, the Canadian government issued its own official account.

Long before any liquor board was created to take alcohol under its benevolent wing, Jamaican rum was the mainstay of the Newfoundland diet, with salt fish traded to the West Indies in exchange for rum. When the Government took control of the traditional liquor business in the early 20th century, it began selling the rum in an unlabelled bottle. The product might have remained permanently nameless except for the influx of American servicemen to the island during World War II. As the story goes, the commanding officer of the original detachment was having his first taste of Newfoundland hospitality and, imitating the custom of his host, downed his drink in one gulp. The American’s blood-curdling howl, when he regained his breath, brought the sympathetic and curious from miles around rushing to the house to find what was going on. The first to arrive was a garrulous old American sergeant who pounded on the door and demanded, “What the cripes was that ungodly screech?” The taciturn Newfoundlander who had answered the door replied simply, “The Screech? ’Tis the rum, me son.” Thus was born a legend. As word of the incident spread, the soldiers, determined to try this mysterious “Screech” and finding its effects as devastating as the name implies, adopted it as their favorite

.

According to author Professor Pat Byrne, a longtime scholar on Newfoundland traditions at Memorial University in St. John’s, the Screeching-In ceremony itself can be an elaborate affair in which the person being initiated stands before the chief Screecher, dressed in traditional Newfoundland fishing garb, which to outsiders can best be described as the yellow outfit worn by the fellow on a box of Gorton’s frozen fish sticks. The initiate is given a few Newfoundland delicacies to eat, such as “Newfie steak,” known elsewhere around the world as bologna. The person is even asked to kiss a freshly caught cod as a sign of respect toward the importance of the fish in the economy of Newfoundland. This is followed by a series of questions the Screecher asks, in a heightened accent, which in turn is supposed to elicit a set response from the initiate.

SCREECHER:

Is we Newfies?

INITIATE:

Deed we is, me old cock, an’ long may yer big jib draw.

SCREECHER:

Did ye j’st go down on yer knucks and kiss a smelly old codfish?

INITIATE:

Deed we did, me old cock.

SCREECHER:

Did ye j’st wrap yer chops around a piece of Newfie steak and gobble some dried caplin?

INITIATE:

Deed we did, me old cock.

As Professor Byrne points out, this question-and-answer period can go on for as long as the master of ceremonies wants to ask questions.

SCREECHER:

Did ye all j’st repeat a whole lot o’tings ye don’t un’erstand a-tall?

INITIATE:

Deed we did, me old cock.

Once the last question is answered, the person is given a large shot of Screech to down in a single gulp, to the applause and cheers of those around them. An actual certificate is even presented, bearing witness to the event and making the person an honorary Newfoundlander.

In the days following September 11, hundreds, if not thousands, of stranded passengers went through some variation of the Screeching-In ceremony across the island. Usually it wasn’t as elaborate or as time-consuming as an official ceremony. But in every town, from Stephenville in the west to St. John’s in the east, a Screecher held a rotting cod in his hands and had people line up to kiss it. It was the natives’ good-natured way of sharing a little bit of their past with their guests. Nowhere was that enthusiasm greater than in Gambo at the Trailways Pub. By some estimates, more than 150 of the 900 passengers were Screeched-In over a two-day period.

Without question, the Trailways was the most popular spot in Gambo during these days. Every night the passengers came in and drank the place dry. And every day the owners sent one of their bartenders twenty minutes down the road to Glovertown to load up on supplies to restock their coolers. Over three nights they went through more than two hundred cases of beer, more kegs than they could count, and enough hard liquor to embalm a herd of moose.

By Friday night the bar was so full that people were spilling out through the back door. After spending a quiet Thursday evening at George and Edna Neal’s home, the gang—Deb Farrar, Winnie House, Lana Etherington, Bill Cash, Mark Cohen, and their newest member, Greg Curtis—decided to let loose with a final night at the pub. They all felt there was a good chance they would be leaving on Saturday and so this was probably their last night together.

When word reached some of the locals that Winnie was a Nigerian princess, the daughter of an African chieftain, they knew they needed to bestow their highest honor on her. She needed to be Screeched-In. By this time in the evening, Winnie had already been drinking a fair amount of wine and was up for anything.

Jim Lane, a volunteer firefighter, was the designated Screecher in Gambo, and for the past two nights he’d been a busy man. Passengers were eager to be Screeched-In and Lane was glad to oblige. Dressed in the traditional yellow oilskin and sporting a most unkempt and dirty phony white beard, he created a mini-ceremony that may have been short on tradition but was long on enjoyment. Also making an appearance on Friday was the same rotting codfish he’d been using all week. Time was not kind to this fish and Lane had to hold the slimy cod carefully to keep its guts from spilling out.

Lane was honored when he learned that Winnie was interested. He did his best to explain the ceremony to her, but her attention span at that moment was somewhat limited. He recited her one line—“Deed we is, me old cock, an’ long may yer big jib draw”—and asked her to repeat it for practice. Winnie squealed with laughter.

Lane warned her not to laugh when he asked her the official question.

“Are you ready, me dear?” Lane asked.

“Yes,” Winnie said, trying to straighten herself up.

“Okay,” he said, falling into character. “Is we Newfies?”

“Deed…me cock…” Winnie said, bursting into fits of laughter.

Every time she made a mistake they had her drink another shot of Screech. And while such penalties aren’t an actual part of the regular ceremony, in this case it was plain fun.

“Is we Newfies?”

“Deed we…” she said, followed by more laughing.

Finally, after two or three times, she came close enough for Lane to accept it. After all, he didn’t want her to get too drunk.

“Now kiss the cod,” he told her, holding the five-pounder to her face.

“I can’t kiss that.” Winnie shuddered.

“Ah, but you must kiss the cod,” Lane explained.

In unison, those around them began chanting, “Kiss the cod! Kiss the cod!”

“I can’t, I can’t,” she squealed, her voice so high it could attract wolves.

Lane moved the fish closer to her face.

“I can’t, I can’t,” she said, closing her eyes.

Lane didn’t know what to do. If she didn’t kiss the cod, he couldn’t give her the Screecher certificate. And after she had come all this way, he didn’t want to see her fail. Then it dawned on him. He’d have to give her a little help.

Ever so gently, he flicked his wrist and thwapped her on the mouth with the head of the fish.

“Eeewwww!” she screamed.

But it was over, she’d have her certificate, and everyone cheered.

T

he second half of the evening was marked by the introduction of a karaoke machine. People were more than eager to sing, and onstage the karaoke went nonstop. To describe the singing as awful would be charitable, but then again, the purpose of these machines is for people to become entertaining at the expense of the song. There was hope, however. The Beatle Boys were in the house.

Since she’d first met them on the flight, Jessica Naish wanted to hear them sing. Having spent three days with them only made her more curious. Peter Ferris, who assumed the role of George Harrison in the band, was willing to get up and sing for the crowd. But Paul Moroney, the John Lennon of the group, was against it, which in a way should have been expected, since Lennon was always the moodiest of the Beatles.

Naish kept nagging for Moroney to play and encouraged others in the pub to do the same. Her Yoko-like behavior eventually paid off. It wasn’t that Moroney was trying to be difficult; he was afraid of sounding bad since his voice wasn’t well rested. Moroney and Ferris whispered for a few moments, trying to decide what song was appropriate. Finally, Moroney walked over to the karaoke machine by himself. A few people closest to the stage area quieted down.

“This is a song by John Lennon,” Moroney said, without any other comments. As the music came up, he stepped to the microphone.

Moroney’s fears were unfounded. He was in fine voice. More important, his tone, his styling, matched Lennon’s perfectly. Naturally, having a pretty liquored-up crowd didn’t hurt either. Standing off to one side of the room, Ferris watched as more and more people in the bar stopped what they were doing and turned their attention to Moroney.

As he moved into the second verse of “Imagine,” the bar was largely silent, with all eyes on Moroney. A few people mouthed the words along with him as he sang. Most just watched and swayed. Given the events of the last seventy-two hours, Ferris knew the lyrics had taken on a special meaning; the hope of being able to live life in peace. And seeing the expressions of those around him made it clear that he wasn’t alone. He even noticed a few people becoming teary-eyed. In all his years of performing with the group, Ferris had never seen people react so emotionally.

As the song came to its conclusion, the last notes hung in the air for a few seconds and the pub was still. Then all at once people were clapping and cheering and hollering for more. Moroney tried to walk offstage, but several people pushed him back. There was no room for debate.

Ferris joined him onstage and they quickly settled on a few more songs. Since the pub was packed with their fellow passengers from Continental Flight 5, they decided “A Hard Day’s Night” was appropriate to commemorate the thirty hours they’d all spent together on the plane. From there they segued into “Eight Days a Week”—a prediction as to how long they would probably be stranded in Gambo. Ending on an optimistic note, they sang “We Can Work It Out.”

Each song had everyone dancing and singing and carrying on as if it were the actual Beatles. The room was hot and sweaty. Onstage Ferris imagined this must have been what the Liverpool pub the Cavern was like back in 1961 when the real Beatles had played there.

Nobody was happier than Naish. She bopped along to the music, screaming like a teenager seeing the Fab Four for the first time on

The Ed Sullivan Show

. After extolling their talents to everyone all night—without ever having heard them sing—she felt inextricably linked to them. Just before Moroney had gone on, Naish was hit with the thought: What if they aren’t any good?

She needn’t have worried. They were boffo.

For the rest of the night, they weren’t Paul Moroney and Peter Ferris, or even their alter egos, George Harrison and John Lennon. They were the Beatle Boys. Everyone called them the Beatle Boys. The Newfies, of course, said it so fast it sounded like one word—theBeatleBoys. Long after they left town, locals would remember them as theBeatleBoys. As in: “Ay, buddy, you should have been here the night of theBeatleBoys.”

Actually, they could make it seem even more compact. Pronounced as fast as humanly possible, it sounded more like “daBeedaBys.” All night long Friday, the cry went out: “Another round for daBeedaBys.”

“And don’t forget the princess!”