The Dead Duke, His Secret Wife and the Missing Corpse (34 page)

Read The Dead Duke, His Secret Wife and the Missing Corpse Online

Authors: Piu Marie Eatwell

The lack of information about Joseph’s fate left me with a feeling of frustration. I had sensed the desperation in Fanny’s letters. She had wanted, so much, to know what had happened to her brothers, to the family from whom she had been separated as a child. Irrational and illogical though it was, I felt I had let her down. As far as I could see, Joseph had vanished for ever: he had been excised by the hand of Victorian censorship, wiped clean from the slate of history. Did a vital clue lie buried in some obscure archive or pile of letters, hidden in a long-forgotten drawer or crumbling to dust in an attic? For the present, I could not tell. The figure of Joseph remained an obstinately elusive question mark, hidden in the inscrutable folds of the past that blanketed him like a pall.

I had now come to the end of my investigation of the Druce affair. Or perhaps, it would be more correct to say, I had reached the furthest point I could. For the picture I had uncovered was not so much in the form of a puzzle, to which there was a neat solution, merely requiring the finding and replacing of missing pieces. It was more like a reflection seen through a glass darkly, growing brighter and brighter and revealing more of the underlying pattern as it was polished, but never finally reaching gleaming perfection. The writer Kate Summerscale, in her book

The Suspicions of Mr Whicher

, has defined detective investigations in these terms:

Perhaps this is the purpose of detective investigations, real and fictional – to transform sensation, horror and grief into a puzzle, and then to solve the puzzle, to make it go away. ‘The detective story,’ observed Raymond Chandler in 1949, ‘is a tragedy with a happy ending.’ A storybook detective starts by confronting us with a murder and ends by absolving us of it. He clears us of guilt. He relieves us of uncertainty. He removes us from the presence of death.

And yet, the ‘investigators’ of the Druce affair across the decades – Chief Inspector Dew, J. G. Littlechild, the estate manager turned amateur sleuth Turner, myself many years after the event – all of us had polished the mirror of the past just a little more, revealing another detail of the underlying image. But to re-create it to perfection would be impossible. Worse than impossible, it would be a lie. Because it would imply that time can be recaptured in its entirety – that nothing is lost by the passage of years. But the past is always the past, and something is always lost; just as something is always preserved; and, also, discovered.

In the case of the Druce affair, what had occurred in the past had not simply been lost owing to the natural erosion of time. It seemed, on the contrary, from my investigations, that there had been a deliberate – and partially successful – attempt to cut out entire events, to erase certain people wholesale from the record, in order to facilitate the fighting of the case. The existence of Fanny Lawson and her brothers had been, effectively, hushed up in order to bolster a defence that the 5th Duke was incapable of fathering an heir. Even before the Druce claim was filed, the splitting of Fanny Lawson from her mother and brothers in early childhood was clearly an attempt to dilute the impact of their presence, so much more glaringly obvious if they had remained together as a family. It echoed the deliberate fragmenting of his first family that T. C. Druce accomplished, by telling his daughter Fanny that her mother was dead, and sending the Crickmer-Druce children on separate paths.

The Druce affair, in fact, was significant not so much because it was a fraud; or because it was started by a mad woman; or because it was an early example of a media sensation. It was significant because of the light it shed on the lies, deceit and hypocrisy practised by society at the time, and their tragic consequences.

In the course of my investigations, I managed to track down a great-grandson of Fanny Lawson, and therefore putatively a direct lineal descendant of the 5th Duke of Portland. Tentatively, I wrote asking for an interview. The address was a suburban house, a world away from Welbeck Abbey. Several months later, I received a reply. After long and anxious deliberation, the letter stated, the respondent had concluded that he could not help me in my inquiries. He asked that I respect his privacy. Evidently, in one small corner of England, the pain of events that occurred more than a century and a half ago lives on to this day.

Some months after my return from Nottingham, I made my last research trip in relation to the Druce affair. It was a cold, wintry day, and the wind burned my cheeks as I made my way down the winding paths of Kensal Green cemetery. It took almost an hour, and the assistance of the cemetery keeper, before I found what I was looking for. It was the grave of the 5th Duke of Portland.

Despite being the largest plot in the cemetery, it was very difficult to find. When I finally succeeded in locating it, I found it to be extremely plain. It consisted of a pink Peterhead granite slab, surrounded by grey granite kerbs and posts. It, also, had been assailed by the forces of time: the tombstone had been damaged by bombing in the Second World War, and the bronze chains and fittings had been stolen in the 1950s. The inscription read:

S

ACRED

TO

THE

M

EMORY

OF

T

HE

M

OST

N

OBLE

W

ILLIAM

J

OHN

C

AVENDISH

B

ENTINCK

S

COTT

F

IFTH

D

UKE

OF

P

ORTLAND

.

B

ORN

17

TH

S

EPTEMBER

1800.

D

IED

6

TH

D

ECEMBER

1879.

For a few minutes, I stood at the grave in contemplation. I could not help thinking that, with this plain and simple monument overgrown with the bushes that he ordered to be planted there, the 5th Duke had finally achieved his aim in life, which was to disappear completely from view. I was sure, too, that he would have been proud of his grandsons’ distinguished careers in the service of their country, had he known about them, and equally pleased that his subsequent progeny had vanished from the public gaze, into the crowds of ordinary folk hurrying about their daily business. It was a fate the duke had always longed to share, but from which he had been precluded by accident of birth and fortune. I watched the sparrows hopping in the bushes, and listened to the wintry wind whistling in the long grass; and wondered how anyone could ever imagine unquiet slumbers, for the sleeper in that quiet earth.

In November 1907, two gentlemen named Calkin, one from Millville, New Jersey, and the other from New Zealand, announced themselves as claimants to the Portland estates. Nothing more was heard of them.

We hope you enjoyed this book.

For an exclusive preview of another Piu Marie Eatwell title, click the link below:

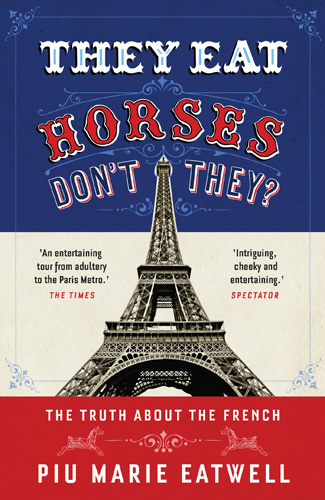

They Eat Horses, Don’t They? The Truth About the French

For more information on

The Case of the Dead Duke

, click one of the links below:

~

More books by Piu Marie Eatwell

An invitation from the publisher

Read on for a preview of

Sex, smoking, fashion,

Film, wine, women,

Painters, poets and Paris...

We all cling to our romantic notions of the French, but what are the truths behind the clichés?

In this entertaining, beautifully illustrated tour of French history, society and culture, Piu Marie Eatwell explores 45 of our favourite myths and misconceptions about the Gallic nation

It was on a sunny August bank holiday that I checked into a hotel in the Latin Quarter of Paris for a weekend break. Almost ten years later, I am still in France. The story is the usual one for many expats in France: meet, fall in love, marry. I never did get to stay in the hotel in the Latin Quarter (spending that whole first weekend with my future husband). But I did get to live in several dodgy apartments in the seedier

arrondissements

of Paris. Over the years, I have spent sweltering summers queuing in traffic jams on the motorways leading to the French coast, and many a winter in the deepest Gallic countryside. Now ensconced in a quiet French village, that first Paris bank holiday seems a world away. Another life.

During my first few years in France, I was excited and enticed by everything around me that seemed quintessentially French. A freshly baked croissant – how French! The rudeness of the waiter at the bistro – how French! The thin and glamorous women who tottered down the Parisian boulevards – how French! A glass of wine at lunchtime – how French! Shopping in the local market – how French!

Gradually, however, I began to notice cracks in this ‘French’ experience. Not all, or even most, of the women I saw were particularly beautiful or glamorous. Every so often, there was a polite waiter. The croissant in the café was tired and crusty. There were McDonald’s and fast-food joints jostling for space beside the cute bistros, with their checked red tablecloths. The supermarkets were stuffed with rows of canned goods. Somehow, however, I ignored these things. They weren’t really ‘French’. The beautiful and glamorous women, the freshly baked croissant, the local market, on the other hand – all these things

were

‘French’. It was as though I yearned after, needed this romantic, glamorous, ‘French’ world to which to aspire, closing my eyes to the reality which was, often, very different.

But the fast-food joints, ordinary-looking women, and supermarkets with rubbishy food were there, all the same. They were, unmistakably, ‘French’. What they were not part of was what I considered the ‘French experience’.

The more I considered this ‘French experience’, the more it seemed to me to consist of certain specific ideas. For example, it most definitely included rude waiters, bistros, glamorous women, smoking and dangerous liaisons. It most definitely did not include fast food, fat women and sandwich lunches. Yet these were things I encountered every day.

And so gradually, I began to see around me more and more the

exceptions

to the so-called ‘French experience’. I began to see how my ideas about France and the French, although some of them were true, were also often a construction of my imagination. I asked around my English-speaking friends back home, and found that they shared a lot of these same preconceptions. And not only that, but there was a whole sub-genre of writing, a mini-industry of ‘Froglit’ – mainly consisting of books written by foreigners who had spent a couple of years in Paris – busy propagating, promulgating, and disseminating the myth of the ‘French experience’. So I listed these common ideas about the French in my notebook and set out to investigate them, poring over tomes in the local libraries and talking to everybody – English or French – that I could persuade to give me some minutes of their time. Were these myths about the French true or false? The results, as you will see, were often quite unexpected.

THE ARCHETYPAL FRENCHMAN WEARS A BERET AND STRIPED SHIRT AND RIDES A BICYCLE FESTOONED WITH ONIONS

‘You aren’t one of those French onion sellers, are you?’ the woman asked Hercule Poirot.

AGATHA CHRISTIE, ENGLISH CRIME WRITER (1890

–

1976),

THE VEILED LADY

,

1923

This is a myth that everybody knows, few believe, and even fewer will admit to having witnessed. This is not surprising, since if you do recall having seen a Frenchman wearing a beret and striped shirt on a bike festooned with onions, you are very likely either to frequent naff fancy-dress parties or to be very advanced in years. In my ten years of living in France, I have never seen any Frenchman on a bike festooned with onions, and only occasionally the odd ageing artist by the

Sacré Coeur

in a striped shirt and beret (and those clearly donned for the benefit of the tourists). And yet the image is ingrained in the Anglo-American imagination as that of the stereotypical Frenchman. Where, exactly, does it come from?