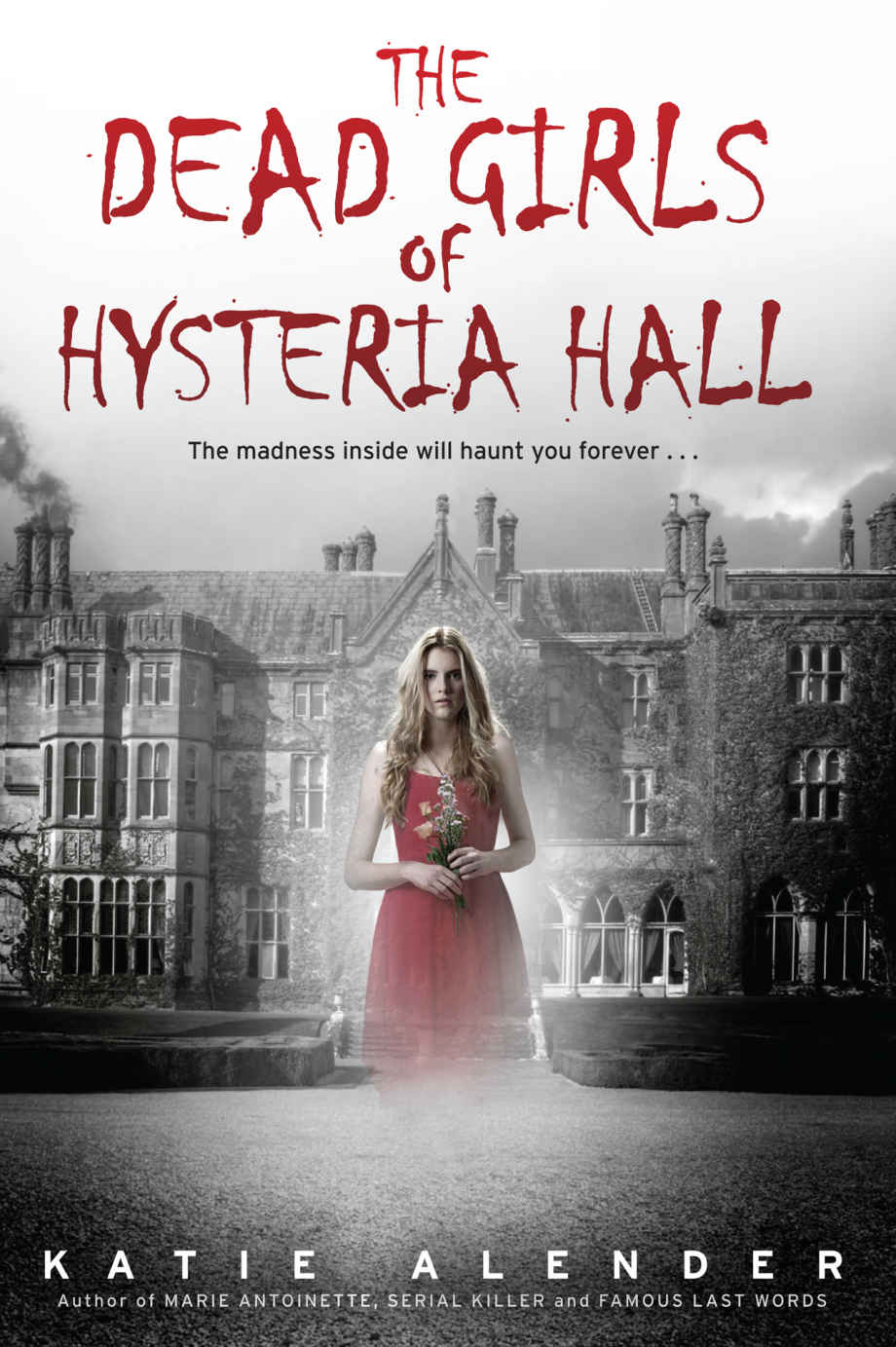

The Dead Girls of Hysteria Hall

Read The Dead Girls of Hysteria Hall Online

Authors: Katie Alender

For Eve, a true friend

CONTENTS

OBSERVATIONS MADE AFTER THE FACT

Every fairy tale starts the same:

Once upon a time.

Maybe that’s why we love them so much. We all get to be part of that story. Just by existing, you get your once upon a time. It’s part of the deal.

What’s not part of the deal, it turns out, is the happily ever after.

Y

ou know that feeling when someone’s eyes are on you—watching you, studying your movement, your breathing? And how it gives you this whole new awareness of how much effort it takes to just stand there like a normal person?

Well, that’s basically how I’d felt for the past three months. Like I was being watched. Stalked …

By my own parents.

Even at a gas station in the middle of nowhere, Pennsylvania, Mom hovered about three feet away from me, her eyes constantly darting in my direction, as if at any second I might decide to run for the hills. But every time I glanced up, she whipped her gaze to something else—a can of Spam, a magazine about crocheting, a package of tropical-fruit-flavored candies.

It was almost like a game. Could I catch her?

Tag! I got you! You’re it!

I never caught her. But I still knew she was looking.

A sinking, suffocating feeling came over my chest.

They were never going to trust me again.

I hunched over my phone and typed

SAVE ME

, then held my breath as the “sending” bar made an agonizing crawl across the top of the screen. Finally, the text went through, and a few seconds later, my best friend Nic’s reply popped up:

<:(

A clown-hat sad face. The saddest kind of sad face there is.

EXACTLY

, I replied, but this time the message failed. I felt a shock of anxiety. I was

intellectually

prepared to be entering a cellular dead zone, but I hadn’t prepared myself emotionally to be cut off from society for two whole months.

Mom leaned toward me, holding up a can of bean dip. “Does that say partially hydrogenated corn oil?” she asked. “I left my reading glasses in the car.”

“Mom,” I said. “You’re a million miles from Whole Foods. Everything here is made of toxic waste. Get used to it. Embrace it.”

She suppressed a shudder, then reluctantly tucked the bean dip into the crook of her elbow.

“You wanted to do this,” I said, an edge of accusation in my voice. I wasn’t going to let her class herself in my category—in the

victim

column.

Unintentionally, her eyes flicked over to my father in the next aisle. “I guess just get whatever you want,” she said. “We’re not going to make it to the grocery store tonight.”

I gave her an aloof shrug and went to troll the aisles, where I passed my little sister, Janie, jittering around with a month’s supply of sugary cereals in her arms. Perfect. Just what she needed, more unnecessary energy. In a family of academics, Janie stood alone. My parents were professors, and I hoped to major in some Romance language (I just hadn’t decided which one yet) and become a scholar of obscure European literature.

Janie’s dream? To someday have her own reality show.

Even her looks set her apart—willowy, with white-blond hair and crystal-blue eyes, where the rest of us were average height, with dirty-blond hair and eyes ranging from gray-blue (Mom) to blue-gray (Dad), with me in between, sporting a color you could probably call “dishwater,” if dishwater had a few redeeming qualities.

Janie was a performer. She was the prettiest, wittiest, most sparkling complete twerp of a human being you ever wanted to backhand on a daily basis. And with all that sugar to fuel her, she’d be insufferable. But what else was new?

Continuing through the aisles, I came across my father, studying a can of chicken. He shook his head. “How can they legally call this food?”

“Spare me,” I said, grabbing a bag of Doritos and a jar of bright-orange queso dip.

My parents were welcome to pretend this was some grand family adventure, but I knew better. We

all

knew better. I was the only one of us willing to admit it.

Mom, Janie, and I converged on the register, Mom’s cheeks flushing pink as the clerk, whose name tag read

TOM

, surveyed our purchases.

“We just drove up from Atlanta,” she said. “That’s why we have all this junk.”

The clerk looked up at her, blank incomprehension on his face.

“Mom, Tom doesn’t care,” I said. “As long as you don’t try to steal anything.”

He grunted gratefully in my direction.

For some reason, my mother assumes strangers are interested in our lives. Maybe because her students spend all their free time kissing up to her and pretending to care about insignificant details of her existence. Mom never met a situation she couldn’t kablooey into an awkward overshare.

“We’re actually going to be staying the whole summer near here,” she went on. “In Rotburg.”

Tom looked up—not at Mom, but at me. “Rotburg, huh? You got family there?”

“Kind of,” my mother said. “My husband’s great-aunt recently passed away, and we’re going to her house.”

“Cordelia Piven,” I put in. “I was named after her.”

Abruptly, Tom stopped messing with the cash drawer. “Her

house

?”

“Yeah,” Janie said, picking a Ring Pop out of a box on the counter and adding it to the pile. “She died and left it to

Delia

. It’s so unfair. She didn’t leave me anything.”

Tom seemed to know that I was Delia, and he set his gaze squarely on me. “You been up there before?”

“To the house?” Mom answered. “No.”

“We couldn’t even see it online,” I said. “The satellite image was all cloudy.”

Pretty frustrating, actually. To inherit a house from one’s old great-great-aunt and not even be able to see what it looked like. The picture in my head had come to resemble a little cottage full of overstuffed floral chairs and ceramic cats (or possibly actual cats).

I’d never met Aunt Cordelia in person, but still, her death had made me a little sad. Back when I was in the sixth grade, she and I had exchanged a series of pen-pal letters for one of my school assignments. We’d long since fallen out of touch, but our brief correspondence had given me a sense of connection with her.

When Mom and Dad had shared the news that she’d passed away and left me everything she owned, I had gone back and looked over her letters. She seemed like a nice old lady, always overflowing with excitement about the tidbits of my life I’d sent her (of course, that could have been nice-old-lady manners). But there was nothing that indicated she felt some deep bond—certainly nothing to suggest that she might someday blow right by my dad’s possible claim to his family’s property and bestow the entire cat-and-crocheted-blanket-filled house on me, a sixteen-year-old.

I suggested we all go to the funeral, but Mom and Dad said there wasn’t going to be one. Which was pretty sad in itself, I guess.

“Oh,” Tom said now. “There’s plenty to see. Where are you all staying?”

Mom and I exchanged a glance. “At the house,” she said.

Tom’s jaw dropped. “You’re staying at Hysteria Hall?”

“Where?” I asked.

Just then, Dad plopped his bags of cashews and roasted almonds on the counter.

“Did you say

Hysteria Hall

?” Mom asked.

“I don’t mean any disrespect,” Tom said. “But that’s what folks call it, on account of the … ah … the women.”

“The women? Brad, have you heard this?” Mom asked.

I sensed a change in my father’s energy—a sudden rigidity in his posture. “We should get back on the road, Lisa,” he said. Dad, for his part, had a way of making authoritative pronouncements as if we were all his royal subjects. Probably from being treated like a minor god-figure by his eager-beaver students. (Sadly, when your parents are professors, college loses a lot of its mystique.)

“But what does it mean?” Mom stared at the counter, as if the answer might lie in the Pick Six lotto tickets displayed under the glass.

“Well, people kind of forgot about the place for a long time,” Tom said, sounding apologetic. “But now they’re all talking about it again because of how she died.”

“And what does

that

mean?” my mother asked Tom. “How did she die?”

“It’s starting to get dark,” Dad announced. “There’s supposed to be a storm this evening.”

“Wouldn’t you like to know, Brad?” Mom turned to him. “I just assumed she passed away peacefully in bed or something. The lawyers never said anything, come to think about it.”

“I’d definitely like to know,” I said.

When I spoke, my parents realized that Janie and I were listening to every word of the conversation.

Dad glanced from my little sister to me and then handed his credit card over the counter. Tom swiped it and passed it back.

“They

did

, actually,” Dad said to Mom, a tight smile on his lips. “And we can talk about it later.” He grabbed all the bags and started for the door.

“Have a nice day,” Tom called as the door closed behind us.

As we settled back into the car, I sent what I figured might be my last text to Nic in a long time:

HEADING INTO ROTBURG. PARENTS ACTING WEIRD AS USUAL. JANIE WON’T STOP SINGING BOY BAND SONGS.

I watched it send, and then I added one final message:

JUST KILL ME NOW.