The Decadent Cookbook (28 page)

Read The Decadent Cookbook Online

Authors: Jerome Fletcher Alex Martin Medlar Lucan Durian Gray

ANDY’S

T

OOTHACHE

by J.K. Huymans

Tonight des Esseintes felt no desire for the taste of music; he contented himself with a small glass of Irish whiskey.

He settled comfortably into his armchair and slowly breathed in the scent of fermented oats and barley; a sharp reek of creosote tarred his mouth.

Bit by bit, as he sipped, his thoughts began to circle around the quickening sensations of his palate, tracking the flavour of the whiskey and reviving memories, through a fatal coincidence of odours, that he had thought long-buried by the years.

The bitter efflorescence of phenol reminded him vividly of a taste that had filled his mouth when dentists last worked on his gums.

His reverie began with a scattered conspectus of all the practitioners he had known; then it converged on just one of them, a character whose eccentric appeal had remained deeply etched in his memory.

It had been three years ago; he had been seized by a violent toothache in the middle of the night. He had stuffed his cheek with wadding and paced up and down his room, banging into the furniture like a madman.

The tooth was a molar that had already been filled. Further repair was out of the question; only a dentist’s pliers could kill the pain. He waited feverishly for daylight, ready to face the most excruciating operation as long as it put an end to his sufferings.

Cradling his jaw, he wondered what to do. The dentists who normally treated him were rich businessmen who made appointments at times that suited them. Visits had to be arranged in advance. “It won’t do,” he said, “I can’t put it off any longer”. He decided to take his chances with one of the popular tooth-pullers—iron-fisted men who knew nothing of the useless art of patching up holes and drilling away decay, but who could whip out the stubbornest tooth at unrivalled speed. They opened early for business and did not make you wait.

At last the clock struck seven. He rushed out into the street, biting his handkerchief, forcing back tears, thinking of a well-known mechanic who styled himself a cut-price dentist and lived on a corner by the canal.

He reached the house. It was recognizable by a vast black wooden sign where the name GATONAX was painted in enormous pumpkin-yellow letters, alongside two small glass cabinets where rows of plaster teeth nestled in gums made of pink wax, hinged together with brass springs. He panted, sweat bathing his temples. A horrible pang of fear ran through him, shivers raced over his skin; then he grew calmer, the pain eased, the tooth quietened down.

He stood stupidly on the pavement. Finally, steeling himself against his terror, he climbed a dark staircase, four steps at a time, to the third floor. There he found a door where an enamel plaque repeated the name on the sign outside, this time in bright blue letters. He rang the bell, then caught sight of the large red blobs of spittle that splattered the steps; appalled, he made a sudden decision to put up with toothache for the rest of his life; he turned to go, but a piercing shriek tore through the partition walls, filling the stair-well and nailing him in horror to the spot. At the same time the door opened and an old woman asked him to step in.

Shame won the battle with fear; he was led into a dining-room; another door banged open, revealing the ghastly figure of an old soldier, stiff as a board in a black riding-coat and trousers; des Esseintes followed him through to an inner room.

From then on his sensations became confused. He vaguely remembered collapsing into an armchair in front of a window and sputtering, with one finger on his tooth, “It’s already been filled; I don’t think there’s anything you can do.”

The man immediately cut short his explanations by poking an enormous index finger into his mouth; then, muttering under his curled and varnished moustache, he picked up an instrument from the table.

The show now began in earnest. Gripping the arms of the chair, des Esseintes felt a cold sensation on his cheek, thirty-six candles flashed before his eyes, the most hideous pains shot through him, he drummed his feet and bellowed like a beast in a slaughterhouse.

There was a cracking sound and part of the molar broke off; he felt as if his head was being wrenched from his shoulders, his skull shattered; he went mad, screaming at the top of his voice and furiously fighting off the man who rushed at him again as if he was trying to get his arm down into his stomach. Suddenly the man stepped back, lifted des Esseintes bodily into the air by his jaw, then brutally dropped him onto his backside in the chair, staggered upright, panting with effort, his frame blocking the window, and brandished the blue stump of a tooth, dripping with red, at the end of his pincers!

Annihilated, des Esseintes threw up a bowlful of blood, waved away the old woman’s offer of the tooth wrapped in newspaper, paid two francs, and added his own bloody globules of spittle to the stairway before fleeing to the street; outside he felt suddenly joyful, ten years younger, and fascinated by the smallest thing…

J.K. Huysmans,

À Rebours,

IV.

HAPTER

10

HE

I

MPOSSIBLE

P

UDDING

A pre-eminent, possibly unassailable, candidate for the title of Decadent Pâtissier of All Time is Marie-Antoine Carême (1784-1833). His masterpieces would probably have been too namby-pamby for De Sade - there’s a noticeable lack of breasts, buttocks and genitalia in his repertoire - but he had other Decadent qualities. He was a mad perfectionist, theatrical, luxurious, obsessive and extreme. ‘The fine arts,’ he once wrote, ‘are five in number: painting, sculpture, poetry, music, architecture - whose main branch is confectionery’.

His first job was as a kitchen assistant in a Paris restaurant. From there he graduated to Bailly’s

pâtisserie

in the Rue Vivienne, spending his free time copying architectural drawings in the print-room of the

Bibliothèque nationale.

One of Bailly’s customers was the Foreign Minister, Prince Talleyrand, who took on Carême as his chef, and was soon using his magnificent culinary talents to dazzle foreign ambassadors into acquiescence. After this spell as an unofficial arm of French diplomacy, Carême went on to direct the

service de bouche

of the Prince Regent of England (the future King George IV), Tsar Alexander I of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the British Embassy in Paris, the Prince of Württemberg, the Marquess of Londonderry, Princess Bagration, and Baron de Rothschild. He specialized in fantastic sculptures of meringue, pastry, spun sugar and fruit, and the list of his

pièces montées

includes creations that would seem to belong more to the opera-house than the table: harps, lyres, globes, military helmets, trophies of war, pyramids, vases, a Chinese hermitage, an Indian pavilion, a waterfall with palm-trees, a rustic cottage, a Venetian gondola, the ruins of Palmyra, etc. After replicating almost the whole world in edible form, this temperamental and brilliant man died aged 50, ‘burnt out by the flame of his genius and the charcoal of the roasting-spit.’

The following recipes, none of which should take more than 30 or 40 hours to prepare, are taken from

French Cookery: comprising L’Art de la Cuisine francaise; le Pâtissier royal; le Cuisinier parisien, by

the late M. Carême, some time Chef of the kitchen of His Majesty George IV, translated by William Hall, cook to T.P. Williams Esq., M.P., and conductor of the Parliamentary Dinners of the Right Honourable Lord Viscount Canterbury, G.C.B., late Speaker of the House of Commons

(John Murray, London, 1836).

ROS

MERINGUE

À

LA

P

ARISIENNE

![]()

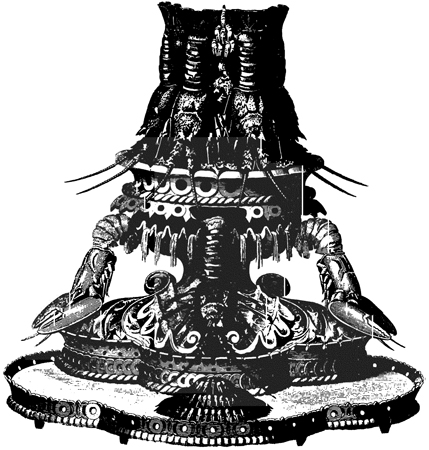

This is actually seven recipes in one. The finished article is a pastry globe coated in meringue, studded with miniature choux-buns and pistachios, and filled with macaroons, strawberries and whipped cream. It balances on three drum-shaped cakes of increasing diameter, each drum made up of several minor cakes, wafers, meringues, nougats and biscuits. It looks more like a monument to the Spirit of Enterprise than a pudding, and the calories it contains, if converted into an alternative form of energy, would have heated Napoleonic Paris for a weekend.

Before you start trying to create this colossal dish, prepare the necessary

pâte d’office, gaufres aux pistaches, petits pains à la Duchesse, meringues, petits choux, nougats,

and

croquignoles

. Carême’s recipes for these are given after the main recipe.

![]()

Make three pounds of Pâte d’Office. Cut this paste in four portions, mould them, and roll them out of the thickness of one-sixth part of an inch. Lay one on a large baking sheet slightly buttered, cut it round twenty inches in diameter; lay another on a smaller sheet, cut it fifteen inches wide, and a third ten inches wide.

Cover with the remaining paste two moulds slightly buttered, each forming a dome, which, when united, compose a perfect globe eight inches in diameter. Cut the paste round, about one-fourth of an inch from the rim of the mould, prick the paste with the point of a knife that the air may escape; place them on baking-sheets.

Make yet another sheet, six inches wide, and the thickness of the others. Fold up the trimmings, and roll them in round bands half an inch thick, divide them in columns three inches long, lay them on a buttered baking-sheet.

Wash the four sheets over with egg, and prick them; put all of them in an oven of a moderate heat, and when the domes begin to colour remove them from the oven, and turn the sheets that they may take an even colour. Then take them out, as also the supports when throughly dry.

Make forty pistachio wafers (see

Gaufres aux Pistaches

*) three inches long by two and a half wide, and fold them over the gaufre-stick. Make also sixty

Pains à la Duchesse

* two inches long; let the

Gaufres

and

Pains

be of a light colour.

Trim the edges of the domes, and then with the point of a knife make an opening one inch wide in the centre of one of them; in the other an opening, also, two inches and a half wide.

Whip six whites of eggs very firm, and mix them with eight ounces of finely sifted sugar, as for

Meringues

*; put half of this mixture over each dome, spread it with a knife (of an equal thickness), and throw fine sugar on it; set them in a mild oven, and give them a light colour.

Glaze the

Pains à la Duchesse

with caramel sugar; trim; and having wetted the edges of the boards with whites of egg, dip them in red or green chopped almonds, or in coloured sugar grains.

When the domes are thoroughly dry, whip six other whites of eggs, and mix eight ounces of sugar with them, as before, and form with the mixture thirty small

Meringues

one inch wide, and of the same height; mask them with sugar through a silk sieve, and when it is melted throw over them some sugar in grains, and put them in the oven directly, laid on a board.

Then make one ordinary-sized

Meringue

, round; finish it as the others, and place it beside them. Have half a pound of fine green pistachios (skinned), and each divided in two fillets only; then spread half the remaining white of egg, very even, over the dome, with the small hole, and strew fine sugar over it; this is to keep the pistachios fast, which stick upon it symmetrically, with the points upwards, leaving six straight places, on which the

Meringues

are afterwards to be placed (see the design). Strew sugar (in grains) over the pistachios only. Put it into a very slow oven. Dispose of the other dome in the same manner, but letting the points of the pistachios bend downwards.