The Detachable Boy (3 page)

Ravi re-packed the secret compartment and lovingly snapped the catches shut. ‘Look after it, John Johnson, and it will most certainly look after you. Now, we must find out how much you weigh.’

‘Why?’

‘Because the cost of postage depends on how much you weigh, best buddy. It will be significantly cheaper than a standard ticket on an aircraft, with the added bonus of not needing a passport if you’re a parcel. Even so, it will be much more than we have at our disposal. We also have the problem of spending money when you arrive at your destination.’

I was taken aback. This was something I hadn’t considered. Then I remembered Nick’s piggybank. ‘It’s okay. I can borrow the money . . . sort of.’

Ravi was horrified when I explained. ‘Mr Lazybones! You would rack up sixteen lifetimes of bad karma. No, let us think.’

‘We have no time. Crystal is in danger.’

Ravi tapped his nose. ‘Come, listen to my plan.’

I

CALLED

M

UM

on Ravi’s mobile after school and let her know I’d be late. I said I’d been invited to Ravi’s place and Mr Carter would bring me home. Then I followed my friend into the butcher’s shop on Claxton Street and watched as Ravi spent every last cent we had on offal. Bones, tripe, ox tongues, liver, kidneys and two big handfuls of bloodied sheep’s brains. I held the bags wide as I carried them back to Ravi’s place but they occasionally brushed my leg, sending shivers of disgust through my body.

With tape and black plastic and Mr Carter’s puzzled permission, we blacked out the garage beneath the house. We made a paper banner that proclaimed the garage as ‘JOHN AND RAVI’S HOUSE OF HORROR’. We shifted tables and boxes to make an entry and exit and arranged torches on strings as spotlights.

Kids and their parents began arriving some time before six o’clock. Before I had disassembled and Ravi had put the finishing touches to the display, the line stretched down the drive, onto the footpath and out of sight.

‘Now, best buddy,’ Ravi said. ‘Are you ready?’

‘Ready as I’ll ever be,’ I said. There weren’t just butterflies in my stomach; there was a massive flock of budgerigars in there.

Ravi closed his eyes as he lifted my detached head by the hair. ‘Are you sure this doesn’t hurt?’

‘Positive. Think of my head as a talking football. Honestly, it doesn’t hurt.’

‘I may never get used to that idea.’ He gently lowered my noggin into an empty fishbowl. ‘Can you breathe? You won’t be able to breathe!’

‘I’ll be fine,’ I said, suddenly confident. ‘I can hold my breath for hours. Let’s do it!’

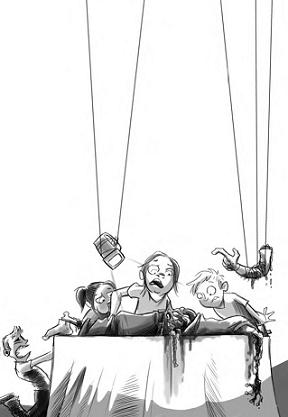

To begin with, I played dead. My clothed legs were attached to my torso on a mock operating table. With my T-shirt lifted, my stomach was exposed and Ravi had arranged a slab of blood-soaked liver over my navel as though it had been lifted from my insides. Meat-streaked leg bones had been stuffed in my limp shirtsleeves so it looked as though my arms had been stripped of their flesh and fingers. That display became true horror when my leg twitched or my chest inhaled.

One of my arms had been tied to the top of an old desk and the hand covered in mashed sheep’s brains. As the arm struggled to free itself it splashed grey matter on customers who strayed too close.

The other arm had been painted with blood and suspended from the ceiling in a darkened corner. That arm and hand caused more squeals than any other exhibit that night. It tapped unsuspecting customers on the shoulder as they passed or stroked their hair with its sticky fingers before swinging out of reach.

But the pièce de résistance was my head in the fishbowl by the exit door, illuminated by flashlight from underneath in true spooky-camping-story fashion. Eyes closed, I waited for the right moment.

‘It looks so real.’

‘It’s wax.’

‘No, it’s not wax.’

‘Creepy.’

‘I swear, it’s just about to . . .’

And then I’d open my eyes.

Later, as the evening dragged on and still a steady stream of people was coming through, I started playing. I whispered at the glass and licked my lips. I pretended to sneeze, I screamed, I yawned, I burped and excused myself and at one stage made a fully grown man yelp by saying “Potato chip!”.

It was after eleven when Mr Carter appeared from upstairs to close down the operation.

‘Okay, Ravi, you’ve had your fun. It’s getting late.’

Ravi collected my pieces and discreetly led me through to the shower. I washed and changed while Ravi cleaned the garage and at the end of it all, we dropped into chairs.

Ravi hoisted a cloth sack onto my lap, his arms trembling with the effort.

We looked at each other and laughed.

‘Nine hundred and seventeen dollars and eighty-seven cents of Australian currency. Three dollars and twenty-five cents from New Zealand and a euro.’

‘How? But . . . that’s amazing. How did we end up with the foreign money and the eighty-seven cents? Didn’t we agree on a single dollar entry fee? Surely there weren’t nine hundred customers.’

‘There were a few . . . ah . . . donations,’ Ravi said, and nodded to the remains of his porcelain piggybank heaped on the bench.

‘No,’ I said. ‘You shouldn’t have done that.’

Ravi shrugged. ‘Piggies are made for smashing. Besides, Crystal is my friend too, remember?

I stared at the bag. ‘I’ll pay you back.’

Ravi shook his head. ‘No need. You’re the one putting his life in the hands of Australia Post.’

I swallowed, and handed the bag of cash to Ravi.

‘I’ll meet you at the post office at two o’clock. Two-thirty at the latest.’

‘I’ll be there with small coloured ribbons in my hair.’

‘Ribbons?’

‘Well, not literally. It’s a saying.’

‘Be there with bows on.’

‘Yes, that.’

‘Thank you, Ravi,’ I said, and shook his hand. ‘You really are a champion.’

Ravi gave a little bow. ‘My pleasure to be of service.’

Mum was still clanging about in the kitchen when I made it home.

‘Hello darling,’ she said. ‘Did you have a good night?’

‘Yes, we um . . . had fun.’

‘What have you got there?’ she said, pointing at the suitcase.

‘It’s Ravi’s collection of . . . wild animal droppings. Want a look?’

‘No thanks dear. Off to bed with you, now. Run along.’

Nick was snoring but it sounded more like a purr. I put my pyjamas on and crawled into bed but I couldn’t sleep. After wriggling about for ten minutes, I got up and spent the best part of an hour pulling myself apart and getting into and out of the case. I eventually found a sequence that made sense. Feet first, then legs. Next I detached my head and lowered it into the case before my arms manoeuvred my torso into position. Arms detached and hands dragged them into their own compartment before placing the dummy in my mouth. My hands closed the lid from the inside and I locked it with my tongue. It was dark in the case and for the first few minutes, I battled with claustrophobia, panicking that I might not be able to get myself out again. It must have been like a Normal kid learning to trust a diving snorkel. You’re not going to die. No, you won’t be locked there for ever. When my head convinced itself it was safe, the panic passed and the foam-and-velvet-lined box became deceptively comfortable. So comfortable you could easily just close your eyes and . . .

‘W

HERE’S

J

OHN?’

Mum said. ‘John?’ she squeaked. There was mild panic in her voice.

It was early. I was still locked in Ravi’s case.

‘I don’t know,’ Nick groaned. ‘Don’t open the curtains!’

I heard the curtains open and my brother groaned again.

I heard her footsteps heading down the hall. I hoped Nick had pulled the blankets over his head and wouldn’t see or hear me sliding from the case and reassembling myself on the floor. When I was together enough to sit up, I wasn’t disappointed. Nick was a lump under the covers.

‘I’m here, Mum,’ I yelled. ‘I was in the . . . bathroom.’

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘There you are. Ravi’s here.’

My friend appeared behind her. Something was wrong with him. He was blinking like a camel in a sandstorm, with both eyes fluttering wildly.

‘Ravi?’ I choked. ‘What? What are you doing here?’

‘Nothing, my best buddy. I was just . . . going to the football.’

He was winking at me but he was using both eyes again.

‘Football?’ I said. I swallowed hard, and looked over my shoulder. Mum was standing there, grinning.

‘Yes, you know, the game with the ball . . . kicked with the foot.’

Ravi was blinking furiously. He looked as though he was having a fit.

‘Are you okay?’

‘Yes!’ Ravi whispered. ‘I am winking at you and you are supposed to say something like “Ah, yes, the football.

Just let me get dressed my dearest bestest buddy in the whole world and let me WALK WITH YOU!”’

I dressed, grabbed the case and went outside.

‘What’s the matter? You’re very early.’

‘We have a problem,’ said Ravi. ‘A big problem.’

A shiver went through me. ‘We do?’

‘I made an oversight in my calculations. It seems that Australia Post won’t accept you.’

‘What?’

‘They only handle mail and parcels up to twelve kilograms. I’ve converted all our coins into notes but unless you’ve been on Oprah’s extreme diet since we last spoke, I could predict with confidence that you weigh more than twelve kilograms.’

‘Crud.’

‘No, it’s true, all of it!’

‘I didn’t mean crud, I meant crud !’

‘Oh, I see. Profanity, not disbelief.’

‘Pardon?’

‘Nothing. I was just . . .’

‘Shut up, I’m trying to think.’

‘Don’t do yourself an unnecessary injury, my dearest friend. The fact that Australia Post won’t carry you is not the problem.’

‘Yes it is! It’s a huge problem. My means of transport no longer exists.’

‘I have found a freight service that can transport you. Fred Express. They transport materials from Australia to the USA every day of the year. I can get you a ticket on their aircraft for one hundred and sixty-nine dollars. Guaranteed door-to-door in three days.’

‘Brilliant!’ I said, and swallowed. ‘Three days?’

‘Guaranteed.’

‘But I can’t hold on for three days! That’s not humanly possible.’

Ravi tapped the shiny suitcase in my hand. ‘Remember . . . you don’t have to hold on. That’s not the problem.’

‘What is the problem?’

‘Today’s deliveries close at two p.m.’

‘Two p.m.? That’s okay. We can do that.’

‘Two p.m. at their offices in Mascot.’

‘Mascot? We’ll never make it.’

‘We can make it. We need to be aboard the 12.47 train which . . . if it arrives on time . . . will get us to their offices at approximately 1.46. That’s not the problem.’

I started pulling my own hair. I started jumping up and down. I pretended I was a teapot. I ran at a bus stop and punished the side panel with my head. Thunk thunk thunk.

‘I’m sorry,’ Ravi said. ‘You’re beating your head in frustration, I can tell. The problem is that we had arranged to meet at two p.m. Two-thirty at the latest. With our new plan, that would be totally unsuitable. We need to meet earlier. That is the problem.’