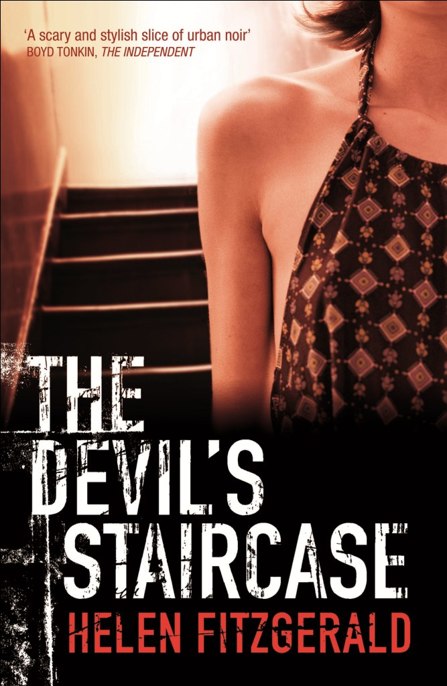

The Devil's Staircase

HELEN FITZGERALD

Helen Fitzgerald was born in Australia and now lives in Glasgow. She worked for the Scottish probation and parole service for ten years. Her other books include

Dead Lovely, My Last Confession

and

Bloody Women.

‘FitzGerald has written something startling, menacing and original. She shows the savagery under our civilised demeanours, which at any moment can come bursting through with dire, far reaching consequences’

Literary Review

‘A terrific, genuinely unputdownable book’

The Bookseller

‘Hilarious coming-of-age romance with extremely violent, serial killing nastiness, all in just over 200 blisteringly readable pages’

Sunday Herald

‘Fast-paced grunge and gruesome horror’

The Age

‘The neo-noir comic misadventures of an original heroine . . .

Brilliant, shocking and unputdownable’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘Lovely, sparse, elegant writing, highly original plot and ever building tension make this book irresistible. Reading it is like stepping over the edge of a cliff, with events spiralling dangerously out of control once Bronny, a naive young Australian, begins sharing a squat with a group of 20-something travellers in London. There’s sex and drugs and rock-and-roll, a whiff of true evil and a scream-out-loud finale. Wow!’

Australian Women’s Weekly

‘Mixing black comedy and violent thrillers is no easy task, but

in this fantastic second novel Australian writer FitzGerald does

it brilliantly . . . Real emotional engagement and an intelligent

subtext’

The Big Issue in Scotland

‘Dark, disturbing and demented – in the best way possible’

HELEN FITZGERALD

This eBook edition published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

First published in 2009 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

This edition first published in 2010 by Polygon.

Copyright © Helen FitzGerald, 2010

The moral right of Helen FitzGerald to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-579-6

Print ISBN: 978-1-84697-149-5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Isabel Anne FitzGerald

It was fifty–fifty. Mum had it, and had died in a pool of her own mad froth. Fifty-fifty for Ursula and for me. Our eighteenth birthday presents – hers now, mine in four years’ time – would be decided by the landing of a twenty-cent piece, a head or a tail.

I tried to hold Ursula’s hand as we walked through the car park and into the hospital, but she flicked me away. After that I only remember corridors, hundreds of them leading to hundreds of others. And I remember sitting in a family waiting-room for hours while Ursula and Dad talked about test results and then I remember Ursula running out of a room with her arms wide open, grinning from ear to ear. I hugged her and we twirled around in the room together. Lovely Ursula. She wouldn’t go the way Mum had gone, to a moody forgetful place that reduced her to stinking incapacity and then ended her at forty.

The darkness descended on the way home from the hospital that afternoon. I was certain that Ursula’s test result meant bad news for me. Dad explained that this was bullshit, but I didn’t believe him. As far as I was concerned, one of us had to have it, and if it wasn’t going to be Ursula, then it was going to be me.

I was fourteen, and from then on my only thoughts would be of death. I would stand still for the remainder of my teenage years, looking into the air at a slowly falling twenty-cent piece.

The drive to Kilburn was a typically boring freeway drive – flat, dry and fast. There were thousands of large loud trucks speeding and overtaking tiny little family vehicles. There were hungry-looking sheep in dry fields and at least two splattered animals on the side of the road. There was a funeral parlour on the outskirts of Kilburn, a cemetery, and pigs squealing at the bacon factory in our street. There was darkness, seeping into me.

I missed out on a lot in those four years:

I never went on the Scenic Railway at Luna Park.

I never kissed a boy in case I began to love him.

I never applied for university.

I never lost my virginity.

I was already dead.

Three weeks after my eighteenth birthday we drove to Melbourne. I imagined I was walking along the corridor of a Texan penitentiary. Instead of yellow-brown paddocks I saw the steel grey of cells. My Dad was the priest, rambling prayers breathlessly one step ahead of me. Ursula was the silent guard, cuffed to me, leaden. I was moving towards the room I’d end in, letting it happen, not stopping it, and when I looked in the wing mirror I noticed I was eating Cheesles. I wondered why people bothered with last meals as I sucked the orange gunge from the rice ring, but then I realised that there should always be time for Cheesles because Cheesles are bloody wonderful.

Dr Gibbons had been part of my family’s life for as long as I could remember, and not in a good way. As kind and as gentle as he was, he represented needles and coffins to me, and whenever his thick old frame appeared a wave of terror overwhelmed me. The wave came over me more than ever as Dr Gibbons took my blood, as he asked me loads of questions, and as he made me sign things. ‘Two to three weeks,’ he said. ‘I’ll call you.’

‘Can I have a few minutes to myself?’ I asked.

‘Of course.’

‘I just need a bit of a walk.’

I left Dr Gibbons and Ursula and Dad standing in the hospital room and walked down the stairs and then outside. I stopped at the car to write a note, popped it on the windscreen, then crossed the six-lane road.

As I weaved my way through the slow-moving traffic, I realised the darkness was going. I didn’t imagine a car coming from nowhere and smashing into the side of me, sending my flattened head and twisted body twenty feet into the air and then down onto the nature strip with a thump. As I walked through the park, I didn’t imagine a man in a large overcoat appearing from nowhere and either (a) pulling a knife from under his coat and slicing my throat from ear to ear or (b) dragging me into the bushes, ripping off my pants and raping me while draining the air from my windpipe with his elbow. As I walked to the other end of the park, I didn’t imagine falling into the man-made lake and getting my feet tangled in weeds and yelling for help but not getting it.

I didn’t imagine anything death-related, for the first time in four years.

I reached the main road on the other side of the park. The hospital had disappeared from view completely by then. I waved down a taxi.

Turning around, I looked at the trail of non-death behind me, took a deep breath, opened the door and said: ‘Tullamarine Airport.’

I hadn’t travelled further than Melbourne since I was ten, and that was only a day trip to see the penguins at Port Phillip Island. It was our first expedition without Mum, intended to cheer us up, but I remember finding the rows of tourists and the waddling penguins scarily similar and feeling a bit depressed that both had ended up in the same place doing much the same thing.

My vague plan had been to travel once I knew the result, to make the most of the years I had left, so I had the passport I’d applied for in my shoulder bag. But after the blood was taken, it hit me that I would have a pretty crap time if I knew I was dying. In fact, knowing was going to be pretty crap full stop.

I needed to

not

know. And I needed to get away now.

The one-way ticket cost $800, two thirds of the amount I’d managed to save at the Craigieburn Mint, where for six months I’d made money, literally. I bought it and ran as fast as I could to the check-in. What if Dad and Ursula found me? What would I say? What if they arrived and begged me not to go? What would I do?

‘How many bags?’

It was the gruff Qantas check-in person, who had obviously been talking to me for some time, and I hadn’t been listening. I’d been thinking about Dad and Ursula racing around corridors and parks looking for me, getting in the car and seeing the note I’d placed under the windscreen wiper.

Dear Dad and Ursula,

I’m sorry but I don’t want to know. I won’t let it take me over. It’s been doing that for years and I’ve been wasting my life. I’m going to London to

live

and I’m going to be fine. I love you both more than ever and more than anything,

Your Bronny.

‘None?’ asked the Qantas check-in person. ‘What do you mean, “none”?’

‘I’m travelling light,’ I said.

He raised his eyebrows before handing over my boarding pass and I ran, just in case they were arriving in the car park, just in case they were racing behind me to shout, ‘Stop!’ because stopping was the last thing I wanted to do.