The Dirt (20 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

I think a lot of RTB’s friends gained a newfound respect for Tommy that night: not only was he built like a skyscraper, not only did he have a never-ending orgasm, but when he was done, he shared. He looked up at the ring of guys around the Jacuzzi staring in shock and amazement, and ordered Honey to work her way around the tub, blowing everyone. It was hard to get that image out of my mind when I sat around the dinner table with the happy couple and Tommy’s parents in West Covina a few months later. She just didn’t seem like the kind of girl you’d want to take home to your mother, unless you were raised at the Bunny Ranch.

I passed on Tommy’s offer, not out of respect for him, but because I was too fucked up to get turned on. In fact, I decided that I wanted to leave the party altogether. I was drug-sick, confused, and wanted to see Lita. The problem was that RTB had the doors locked and blocked, like usual, to make sure no one left too fucked up to drive. To make matters worse, I had no idea where I’d put my clothes.

I ran to the wall and scaled it, completely naked. As I dropped down on the other side, I noticed that the stones had cut up my chest and legs, which were trickling blood. Outside, two girls who couldn’t get into the party were waiting in a ’68 Mustang. “Nikki!” they yelled. Fortunately, I always left my keys in my car then—I still do. So I hopped into my Porsche and gassed it down the hill. The Mustang screeched on the gravel and took off after me. I floored it to ninety, looked back to see if I had lost them, and, as I did so, was suddenly thrown against the dashboard. I had crashed into a telephone pole. It was sitting next to me in the car in a decimated passenger seat. If anyone had been sitting there, their head would have been smashed flat.

I stepped out of the car, in shock, and stood in front of the steaming mess that was once my true love. It was totaled, useless. The girls who were chasing me were gone, probably more scared than I was. And I was alone—naked, bloody, and dazed. I tried to raise my arm to hitch a ride, but a sharp pain raced from my elbow to my shoulder. I walked to Coldwater Canyon, where an older couple picked me up and, without saying a word about the fact that I was butt-naked, drove me to the hospital. The doctors put my shoulder in a sling—it was dislocated—and sent me home with a bottle of pain pills. I spent the next three days unconscious, whacked out on painkillers.

Except for Lita, no one knew where I was. All that the band knew was that my Porsche was lying totaled halfway down the hill, and I was nowhere to be found. To this day, I still wonder how much I was missed: No one ever bothered to call the house to see if I was all right. The only good thing that came out of the experience was that I developed a lifelong love for Percodan.

The car crash, combined with everything else creepy and dangerous that had happened to us, brought me back to reality and Lita talked me into backing off my flirtation with Satanism. Instead, heroin began to consume me, first to kill the pain of the shoulder then later to kill the pain of life, which is the pain of not being on heroin. Vince had found a girl who could hook us up. He’d bring in a brown lump of tar, a sheet of tinfoil, and some kind of homemade funnel made out of cardboard and tape. We’d take a pinch of the heroin, put it on the foil, hold a lighter underneath, and suck up the smoke as we chased the burning ball down the foil. We’d get so fucking stoned we’d just sit on the couch and stare at each other.

Pretty soon, we were getting higher-grade heroin through a bassist who played in a local punk band and was good friends with Robbin Crosby of Ratt. Once the two of them taught us how to use needles, it was all over. The first times I shot up, I just passed out. When I came to, everyone would be laughing at me because I’d have been lying in the middle of the floor for fifteen minutes. Vince’s vice was women and, with those first shots, I learned that mine was to be drugs, for the rest of my life. I invented speedballs without anyone even having to tell me about them. One afternoon, I wondered whether shooting up coke with the heroin would keep me from passing out. So I did my first speedball, and I didn’t pass out. I did, however, spend the fifteen minutes usually consigned to blacking out on the floor of the bathroom, vomiting all over the toilet and floor. But I didn’t mind throwing up. I was always good at that.

Luckily, with one arm in a cast, I couldn’t shoot up on my own. It kept me in check. I couldn’t play bass either, but that was fine with our producer, Tom Werman, because he was constantly calling Elektra complaining that I couldn’t play and Vince couldn’t sing. So I would come to the studio with my arm in a sling and hang out and get high and look after things.

Werman had told me throughout the session, “Whatever you do, don’t look at my production notes. I have things there that I’m thinking about as far as the direction of the music is concerned, and I don’t want you freaking out over them.” Of course, that was the worst thing he could have told us. From then on, we kept trying to find out what he was writing. But whenever he left the studio, he’d take them with him. One evening, when he stepped out to go to the bathroom, he left the notes behind. I ran to the mixing desk, excited to finally find out what was really on his mind. I opened the book and peered at the words: “Don’t forget to mow the lawn on Sunday. Remember to get ballet slippers for school play. Buy new pitching wedge.” I seethed with anger: I could not believe that this person who called himself our producer could be thinking about anything other than Mötley Crüe and rock and roll.

I walked outside to find him, but the receptionist stopped me. Alice Cooper was working in the studio, and I had been begging her for days to let me meet him. He seemed bigger than God. And this was my lucky Sunday. “He’s ready to meet you,” she said. “He said to wait for him in the room outside his studio at three.”

Standing outside his studio at three was an impeccably dressed man in a suit holding a briefcase. “Alice will be out in a second,” he told me, as if I was about to meet the Godfather. A minute later, the door to the studio opened and smoke billowed out. Emerging slowly from the center of the cloud came Alice Cooper. He was carrying a pair of scissors, which he kept opening and snapping shut in his hands. He walked up to me and said, “I’m Alice.” And all I could say was, “Fuck yes, you are!” With an entrance like that, he really was God. It wasn’t until years later that I figured out what that smoke really was.

By the time my arm healed, our second album,

Shout at the Devil

, was finished and we were ready to play live again. When we were living together, we had watched

Mad Max

and

Escape from New York

nonstop, until every image was engraved in our brains. We were starting to get bored with the glam-punk image because so many other bands had copied it, so our look evolved into a cross between those two movies. The metamorphosis began one night at a show at the Santa Monica Civic Center. Joe Perry of Aerosmith was smashed out of his mind, and I walked over to him, took a grease pencil, and smeared it under my eyes,

Road Warrior

style. Joe said that it looked cool, and that was enough encouragement for me. From there, I put on a single studded shoulder pad and war paint under my eyes, like one of the gas pirates in

The Road Warrior

. Then I had someone make me thigh-high leather boots with cages in the heels, which ejected smoke when I pressed a button. We painted a city skyline based on

Escape from New York

as a backdrop to our shows, shaped our amps like spikes, and built a drum riser to look like rubble from an exploded freeway.

WE THOUGHT WE WERE THE BADDEST CREATURES on God’s great earth. Nobody could do it as hard as us and as much as us, and get away with it like us. There was no competition. The more fucked up we got, the greater people thought we were and the more they supplied us with what we needed to get even more fucked up. Radio stations brought us groupies; management gave us drugs. Everyone we met made sure we were constantly fucked and fucked up. We thought nothing about whipping out our dicks and urinating on the floor of a radio station during an interview, or fucking the host on-air if she was halfway decent looking. We thought we had elevated animal behavior to an art form. But then we met Ozzy.

We weren’t that excited when Elektra Records told us they’d gotten us the opening slot on Ozzy Osbourne’s

Bark at the Moon

tour. We had played a few dates with Kiss after

Too Fast for Love

, and not only were they excruciatingly boring but Gene Simmons had kicked us off the tour for bad behavior. (Imagine my surprise seventeen years later when ace businessman Gene Simmons called as I wrote this very chapter, asking not only for the film rights to

The Dirt

but also for exclusive film rights to the story of Mötley Crüe for all eternity.)

We started warming up for the Ozzy tour at Long View Farm in Massachusetts, where the Rolling Stones rehearsed. We lived in lofts and I begged them for the one where Keith Richards slept, which was in the barn. Our limousine drivers would bring us so many drugs and hookers from the city that we could barely keep our eyes open during rehearsals. Tommy and I kept a bucket positioned midway between us, so that we’d have something to throw up into. One afternoon, our management and the record company came down to see our progress, or lack thereof, and I kept nodding out.

Mick, our merciless overseer of quality control, bent into the microphone and announced to the assembled mass of businesspeople and dispensers of checks, per diems, and advances: “Perhaps we could play these songs for you if Nikki hadn’t been up all night doing heroin.” I got so pissed off that I threw my bass to the ground, walked over to his microphone, and snapped the stand in half. Mick was already at the door by then, but I chased him down the country lane, both of us in high heels like two hookers in a catfight.

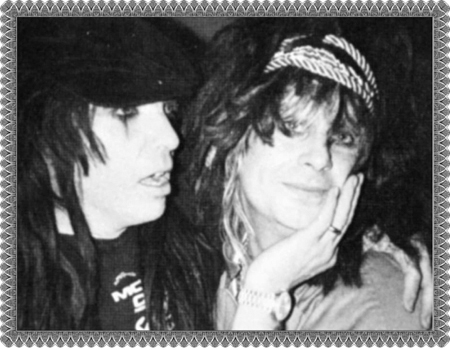

fig. 4

Mick with Ozzy Osbourne

The tour began in Portland, Maine, and we walked into the arena to find Ozzy running through sound check. He wore a huge jacket made of fox fur and was adorned with pounds of gold jewelry. He was standing onstage with Jake E. Lee on guitar, Rudy Sarzo on bass, and Carmine Appice on drums. This wasn’t going to be another Kiss tour. Ozzy was a trembling, twitching mass of nerves and crazy, incomprehensible energy, who told us that when he was in Black Sabbath he took acid every day for an entire year to see what would happen. There was nothing Ozzy hadn’t done and, as a result, there was nothing Ozzy could remember having done.

We hit it off with him from day one. He took us under his wing and made us comfortable facing twenty thousand people every night, an ego boost like no other we’ve ever had. After the first show, a feeling came over me like the one I had when we sold out our first night at the Whisky. Only this was bigger, better, and much closer to the victory line, wherever and whatever that was. The little dream that we had together in the Mötley House was about to become a reality. Our days of killing cockroaches and humping for food were over. If the performance at the US Festival was a spark illuminating what we could become, then the Ozzy tour was the match that set the whole band ablaze. Without it, we probably would have been one of those L.A. bands like London, surefire stars who never quite fired.