The Doctor Makes a Dollhouse Call (13 page)

Read The Doctor Makes a Dollhouse Call Online

Authors: Robin Hathaway

W

hen Fenimore stepped into his office he sniffed. Perfume? And something else was different. Of course Mrs. Doyle's bulky presence was missing. But there was no sign of Horatio, either. In his place, crouched over his filing cabinet, was a scantily clad female figure. She looked up.

hen Fenimore stepped into his office he sniffed. Perfume? And something else was different. Of course Mrs. Doyle's bulky presence was missing. But there was no sign of Horatio, either. In his place, crouched over his filing cabinet, was a scantily clad female figure. She looked up.

“How do you do?” Fenimore said.

“Oh, you must be the doctor.” She pushed a strand of hair from her eyes and stared.

“I don't believe I've had the pleasure ⦠.”

She giggled. “Tracy Sparks. The new temp.”

Mrs. Doyle had mentioned something about hiring temporary help in her absence, but this was the first one he'd seen.

“Hey, Doc.” Horatio ambled in from the kitchen, munching an apple. He tossed another to Ms. Sparks. “For after work,” he said, sternly.

She quickly bent to her filing.

Sal appeared from one of her hiding places. Fenimore picked

her up, glad to find something familiar in his office.

her up, glad to find something familiar in his office.

“What about my lessons?” Horatio asked, without preamble.

Fenimore started visibly. With all the uproar over the Pancoast case, not to mention caring for his other patients, he had completely forgotten about his promise to Horatio. Despite his exhaustion, he said, “Now would be a good time.”

Since the Pancoasts were foremost in his mind, he decided to explain Emily's heart condition. He drew out her file. “Miss Pancoast suffers from a condition called the Sick Sinus Syndrome.”

“I thought we were gonna talk about her heart.”

Fenimore looked at him.

“Aren't the sinuses in the nose? My uncle's always complaining about his. He has terrible headaches and snorts a lot.”

It was going to be a long evening. “This is a different kind of sinus. The word âsinus' means a cavity or hollow. They can be found in many parts of the body. The one I was referring to is a hollow in the chamber of the heart that collects blue blood. This is where the natural pacemaker of the heart is located. It's called the âsinus node.'”

Horatio was paying attention.

“The heart rate varies according to the size of each creature. The larger the creature the slower the heart rate. The whale's heart beats twelve times a minute, a hummingbird'sâsix hundred and fifteen. A normal adult human heart beats anywhere from sixty to one hundred times a minute.” Fenimore pulled his stethoscope from his pocket and handed it to Horatio. “Put those in your ears.”

He obeyed.

Fenimore started to push up Horatio's T-shirt. The boy yanked it off and tossed it in a corner. When Fenimore planted the silver disk on his chest, Horatio jumped. “It's cold!” he yelped.

“That's what they all say.” Fenimore massaged the disk with his hand to warm it and placed it back on the boy's chest a little to left of center. He looked at his watch. When the second hand reached twelve, he told Horatio to start counting.

“One, twoâ” he began under his breath.

When the second hand had completed one rotation, Fenimore said, “Stop! How high did you get?”

“Seventy.”

“Good. I'm happy to inform you that you are a healthy fifteen-year-old. Cardiac-wise, that is,” he modified.

Horatio grinned.

“Now, Emily's heart”âhe took an electrocardiogram from her fileâ“beats at a rate of sixty-two a minute, a normal rate. But there's one problem. Every now and then it slows downâand even stops.”

Horatio blinked.

“Yes. That's not good. And the reason it stops is because her sinus node isn't working well. The sinus node produces the electrical impulse that causes the heart to contract and push the blood around the body. When it isn't working, the blood stops moving around.”

“And she gets dizzy cause her brain's not gettin' enough blood.”

“Right.” Fenimore beamed, pleased that his pupil had remembered so much. “But today we have a way to correct this.”

He fumbled in his drawer and came up with an oblong, shiny metal object about the size of a cigarette lighter.

He fumbled in his drawer and came up with an oblong, shiny metal object about the size of a cigarette lighter.

“A pacemaker,” said Horatio.

“You've seen one?”

“He nodded. On

S&IâScience & Invention

âa TV show.”

S&IâScience & Invention

âa TV show.”

Hmm. Fenimore made a mental note to watch more TV. He tossed the pacemaker at Horatio. Two long wires protruded from one end. He fiddled with them.

“One wire is embedded in the collecting chamber, the other in a pumping chamber,” Fenimore said.

The temp was hovering in the doorway.

Fenimore looked up with a frown. He hated to be interrupted. “Yes?”

“My question's for Mr. Lopez,” she drawled. If she hadn't batted her ample eyelashes in Horatio's direction, Fenimore would have wondered whom she was talking about.

“I'll be with you in a minute,” Horatio dismissed her with a curt nod.

To Fenimore's amazement, Ms. Spark's gaze lingered over Horatio's bare chest a little longer than necessary. He observed his part-time help with new eyes.

Fenimore reached behind him and pulled down a wall chart. The chart revealed a detailed diagram of the heart. He pointed out the collecting chamber and the pumping chamber.

“Once the pacemaker is implanted, when Emily's sinus node fails to produce its electrical charge, the man-made pacemaker senses this and supplies a charge of its own. It keeps doing this until Emily's sinus node begins to work again.”

“Wow!”

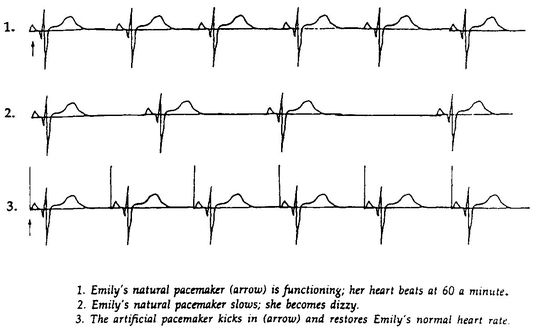

“Yes. It is a kind of miracle.” Warmed by his pupil's enthusiasm, Fenimore sorted through Emily's electrocardiograms and took out three of them. “The first shows her heartbeat when her own sinus node is working; the second shows when it isn't working well; the third shows when the pacemaker kicks in and takes over.”

Emily Pancoast's Electrocardiograms

“But where does the pacemaker get its electricity? There's no plug.”

“A battery. There's a battery inside the pacemaker.”

“But doesn't it give out? I have to buy new ones for my boom box all the time.”

“Absolutely.” He grinned at his bright pupil. “That's why we hitch Emily up to that transmitter you saw down at Seacrest.

They check it every three months to make sure her battery hasn't run down. It has to be replaced about every five years. But it's a minor operation, done on an outpatient basis. She's home the same day.”

They check it every three months to make sure her battery hasn't run down. It has to be replaced about every five years. But it's a minor operation, done on an outpatient basis. She's home the same day.”

“Huh.”

“Is that all you have to say?” He slipped the electrocardiograms back in the folder.

“Cool, man.” Horatio rose and stretched.

“That's better.”

While Mr. Lopez went to confer with his temp, Fenimore lingered at his desk a little longer, feeling oddly satisfied. He liked the feeling. He didn't want to let it go.

Reluctantly he reached for the phone and dialed Detective Rafferty's number.

T

hey were well into their martinis before Fenimore outlined the Pancoast affair to his friend. He was not proud of the part he had played in it so far.

hey were well into their martinis before Fenimore outlined the Pancoast affair to his friend. He was not proud of the part he had played in it so far.

Rafferty looked stern. “I warned you about this amateur dabbling, Fenimore. You'd better leave it to the police.”

“The Seacrest Police have come up with zilch. Now, there are rumors that the state police have been called in. I was only trying to help my friends,” Fenimore protested.

“What would you think if I started dabbling in medicine? Dispensing pills to

my

friends?”

my

friends?”

“That's different,” Fenimore grunted.

“What you're doing is just as dangerous. And just as illegal, I might add.” The policeman polished off his martini.

“Are you going to turn me in?”

Rafferty stared, then grinned. “No. But I seriously warn you off. Have another?”

Over their second martini, Rafferty mellowed and ceased reprimanding

his friend. Fenimore ventured a question. “Any thoughts on the case?”

his friend. Fenimore ventured a question. “Any thoughts on the case?”

“Has it occurred to you that you're too close to these âaunts'âthese old patients of yoursâto evaluate them objectively?”

“Butâ” Fenimore started to object.

“Be honest,” Rafferty stopped him. “Haven't you eliminated them from your list of possible suspects?”

Fenimore stirred uneasily.

“Just as I thought.” Rafferty reached for the menu. “You're too emotionally involved in this case.”

Fenimore waited while his friend decided between pork chops and steak. “But they're both elderly. And one, at least, is in frail health.”

“Too frail to put poison in a piece of pumpkin pie? Too frail to turn a key in an ignition and shut a garage door? Too frail to hammer a few nails into a small shelf ⦠?”

“Too frail to wield a heavy harpoon,” Fenimore parried.

“Just how heavy is a harpoon?” Rafferty countered.

Fenimore shrugged.

“Did you lift it?”

“Of course not. There might have been prints ⦔

“A harpoon is not much heavier than a large arrow. It's built to fly through the air. Anyone of average strength could manage it.”

Fenimore thought of the Red Umbrella Brigade and Doyle's agile octogenarians. He placed his order for bluefish stuffed with crabmeat. When the waiter left them, he said, “But the murderer knocked him out before wielding that harpoon. The

medical examiner found a bump on the back of his head. How could my elderly patient have managed that?”

medical examiner found a bump on the back of his head. How could my elderly patient have managed that?”

“The

back

of the head. The murderer came at him from behind. There was no struggle. He never knew what hit him.”

back

of the head. The murderer came at him from behind. There was no struggle. He never knew what hit him.”

Fenimore mulled over Rafferty's words. Emilyâa murderess? Ridiculous. Judith? Inconceivable. What about Mildred or Adam? Unlikely. Then there was Susanne. Could she have done in her mother, father, sister, brother? Absurd. Frank, the bartender? He had been tending bar on Thanksgiving Day before a host of witnesses. Lastly, reluctantly, he remembered Carrie. Preposterous. All preposterous. What could possibly be their motives?

As if reading his mind, Rafferty said, “Have you come up with a motive?”

Fenimore shook his head.

“There are only a few, you know. Money. Love. Power. Revenge. Or a combination.”

Rafferty had given Fenimore enough to chew on. He turned the conversation away from the Pancoasts, to the Phillies. The two men had a love-hate relationship with that ill-fated team. Although, at bottom, Fenimore was an ardent fan, he couldn't resist needling his friend when the team entered its perennial losing streak. “How does the lineup look this year?” he asked.

“Good. Expect a better than average season.” Rafferty glanced up warily, waiting for one of Fenimore's usual putdowns.

None was forthcoming. Fenimore was too preoccupied tonight to indulge in his ritual teasing.

Â

Â

The meeting with Rafferty had been productive. The next morning, despite a mild hangover, Fenimore was hot on the trail of motives. After receiving permission from Emily and Judith to examine their finances, he placed a call to the First National Bank of Seacrest. Judith had alerted the appropriate trust officer to his call, and after he provided the necessary identification, a bank officer told him how the Pancoast assets were held. At present they were held equally by Emily, Judith, and their recently deceased brotherâEdgarâin the form of stocks, treasury bonds, mutual funds, and real estate.

Fenimore then called the family lawyer, who had also been alerted, and learned how these assets were to be allocated in the event of the death of any of them.

1.

Emily's would go to Judith.

Emily's would go to Judith.

2.

Judith'sâto Emily.

Judith'sâto Emily.

3.

Edgar'sânow that Pamela, Tom, and Marie were deceasedâwould be divided equally among his remaining heirsâSusanne, his son's wife Mildred, and their children. (Fenimore refused to let himself think about the children.)

Edgar'sânow that Pamela, Tom, and Marie were deceasedâwould be divided equally among his remaining heirsâSusanne, his son's wife Mildred, and their children. (Fenimore refused to let himself think about the children.)

So much for money. On to love.

Fenimore's only source for knowledge of the heart was the infamous Seacrest grapevine. He decided that Mrs. Doyle was in a better position to research that. He called her.

“But Doctor, the aunts are too old for love!”

“Nonsense. If your octogenarians are young enough for karate, the aunts are young enough for love.”

“But whoâ?”

“That's for you to find out, Doyle. Keep your ear to that grapevine. The best grapes are probably Mrs. Beesley, the butcher's wife, Frank, the bartender, and Carrie.”

“Oh, Doctor, I couldn't go into a bar alone.”

“Come, come, Doyle. You're behind the times. Haven't you heard of women's liberation? You're free to go anywhere, anytimeâwithout fear of social condemnation.”

Mrs. Doyle gave one of her famous snortsâthe one especially reserved for her employer's judgment.

“Oh, and, Doyle ⦔ he went on, ignoring her rude noise, “keep your ears open for any references to power or revengeâthe other two possible motives.”

“Oh, right.” Mrs. Doyle could no longer hide her exasperation. “Mrs. Beesley is going to tell me that Edgar confided in her one day, while she wrapped up his pork chops, that he harbored a deep desire for her, but Mr. Beesley and Marie prevented him from consummating it. And,” without pausing for breath, “Carrie is going to confess that when she was babysitting for Susanne one day, the children informed her that their mother hadn't gone out at all, but was upstairs entertaining Frank, the bartender, in her bedroom. And Frank will regale me with an account of Mildred's wild passion for Adam, who she pretends to hate. She revealed this to him over a few gin and tonics one night. Emily, of course, will confess during afternoon tea that she was in love with Judith's seaman fiance before Judith ever thought of him, and when he transferred his affections to her sister, she was overcome with jealousy and rage. Judith, on the other hand, blames Emily for revealing the

secret of their planned elopement to her father, and has silently born a grudge for sixty years ⦠.”

secret of their planned elopement to her father, and has silently born a grudge for sixty years ⦠.”

“That's the ticket, Doyle. You've got the hang of it. Now get cracking. I'm counting on you.” He hung upâcutting off another offensive snort.

Other books

In the Garden of Seduction by Cynthia Wicklund

Dark Dealings by Kim Knox

Tommy Gabrini 3: Grace Under Fire (The Gabrini Men Series) by Monroe, Mallory

Love at High Tide by Christi Barth

Black Maps by Jauss, David

The Blue Flower by Penelope Fitzgerald

Rules of Vengeance by Christopher Reich

Biker Billionaire #3: Riding the Heir by Jasinda Wilder

Wart by Anna Myers

Rock My Heart by Selene Chardou