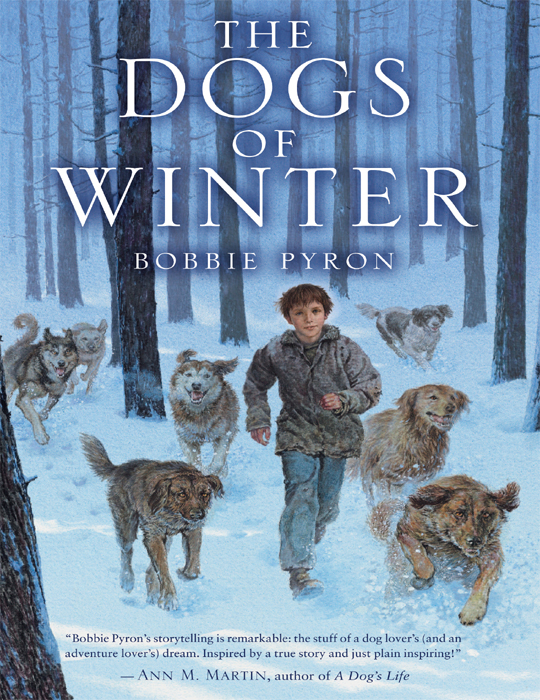

The Dogs of Winter

Read The Dogs of Winter Online

Authors: Bobbie Pyron

I dream of dogs. I dream of warm, soft backs pressed against mine, their deep musky smell a comfort on long, bitter nights. I dream of wet tongues, flashing teeth, warm noses, and knowing eyes, watching. Always watching.

Sometimes I dream we are running, the dogs and I, through empty streets and deserted parks. We run for the joy and freedom in it, never tiring, never hungry. And then, great wings unfold from their backs, spreading wide and lifting the dogs above me. I cry out, begging them to come back, to take pity on this earthbound boy.

It has been many years since I lived with the dogs, but still I dream. I do not dream of the long winter nights on the streets of Russia; seldom do I dream of the things that drove me from my home. My dreams begin and end with the dogs.

Before

he

came, I watched my beautiful mother.

I watched her at the kitchen sink, her pale hands dipping in and out of steaming water as she washed the dishes, humming.

I watched her hang sheets from the line on the tiny balcony of our apartment, clothespins clamped between her teeth. I handed her more clothespins, two by two.

“Such a good helper, my Mishka, my little bear,” she always said.

Before, I sat in my grandmother, Babushka Ina's, lap, and listened as she sang the old songs. She rocked me back and forth, back and forth.

Every morning Babushka Ina walked me down the hill to my school. My mother had to get to her job at the bakery long before the sun rose. At school, I sat at the wooden table and practiced my letters. I learned to sound out “cat” and “rat” and to not watch the birds out the windows.

In the afternoon, my mother and I walked back up the long, low hill to our apartment. Babushka Ina cooked my favorite cabbage soup while I practiced my letters and listened to my mother hum.

Before, it was Babushka Ina who slept with my mother at night. I had my special bed in the sitting room. My mother read to me every night from my book of fairy tales.

This is the way it had always been: me and my mother and my Babushka Ina. This was the way I thought the world would always be.

One warm spring day, my mother waited for me outside the schoolyard. Her eyes and nose were red.

She dropped to her knees and hugged me to her.

“What is it?” I asked.

“She is gone, Mishka,” my mother sobbed. “Your babushka is gone.”

I did not understand why my mother cried so. Sometimes, Babushka Ina took the train to The City to visit her cousin. Once, I had even ridden the train with her.

“She has gone to The City,” I assured my mother. I patted her cheek.

“No, Mishka,” my mother said. “Your babushka has gone to heaven.”

After Babushka Ina went to heaven, my mother began to forget.

She forgot to wash the dishes. She forgot what day to stand in line for macaroni and what day to stand in line for bread.

She cried and cried at night and forgot to take her clothes off to sleep. She forgot to read to me at night. I crawled into bed with her. I could still smell Babushka Ina.

She forgot that Babushka Ina said it was bad luck to cry in your soup, and that vodka and beer were very bad. She sat at the kitchen table and cried and smoked cigarettes and drank.

She never sang again.

My mother forgot to take me to kindergarten, and sometimes she forgot her job at the bakery. Sometimes I went to bed hungry. Sometimes I went to bed alone because she went down to the village at night to meet friends.

I watched her as she sat before the mirror, making herself pretty for a date. Red on her lips, blue above the eyes. “Which ones, little bear?” she asked, holding up one pair of earrings and then another.

She hummed as she pulled on her red coat with the black shiny buttons. She knelt in front of me, hugging me to her. “Be a good boy, Mishka. Lock the door. Don't unlock it until you know it's me.”

If I had known

he

would come, I would never have unlocked the door.

Ever.

His shiny pants and scuffed boots filled the doorway.

My mother pushed me in front of her. “Mishka, say hello.”

“Hello,” I said.

He handed my mother a bundle of flowers, bent down, and pushed his narrow face into mine. “So this is the little man of the house, hey? He's no bigger than a cockroach.”

His smell made my hand want to pinch my nose.

“Shake hands,” my mother urged, giving me another push. He grabbed my hand and squeezed it, hard.

“Don't worry, Anya,” he said. “The boy and I will have lots of time to get to know each other.” His smile was big, but did not reach his eyes.

That was how it started.

He took her out. He bought me a radio for company.

“It is a radio,” I said, holding it up for my mother to see. I twisted knobs and held it against my ear. “I can hear the world talking and singing.”

He snorted. “You won't hear anyone in Russia singing.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because, little boy, everyone's too poor to sing.”

“But we are not poor,” I pointed out.

He threw back his head and laughed. My mother hugged me to her. “No we are not, little bear.”

Soon he forgot to go home. He stayed with cigarettes and bottles of vodka and his scuffed boots next to her bed.

“You're too big a boy to sleep with your mother,” he said. “Only little babies sleep with their mothers. Are you a baby, Mishka?”

I shook my head. “I am five.”

He tossed my favorite blanket and my fairy tale book onto the bed in the sitting room.

“But my mother needs me with her at night,” I said, twisting the hem of my shirt. My mother would move his boots to the sitting room when she came home from work, and put my blankets back in her room. I knew she would.

When she came home from her job at the bakery, she would bring a day-old loaf of black bread, potatoes and cabbage for soup, and a fresh sticky bun for me.

Instead, she came through the door that night with empty hands and a sad face. “I lost my job,” she said.

“You can't lose your job,” he said, his black eyes narrow and hard. “How will we eat?”

“Can't you â”

He cuffed her on the side of the head. I had never seen anyone strike my mother. I waited for her to hit him back. Once, in the village, a bigger boy knocked me down. My mother grabbed the boy and shook him by his collar. The boy's eyes grew wide with fear and he ran away as fast as he could. Just like

he

would.

But my mother did not grab him by the collar. She did not shake him until his teeth rattled. She pressed her hand to the side of her face and said, “I'm sorry.”

After that, they sat in the sitting room and drank and

smoked and laughed and fought.

He

did not like me there, sitting on my bed in the corner.

“He's watching me again, Anya!” he said. “Why is he always watching me?” He stomped across the room and shoved me off my bed. He grabbed my blankets and my book and threw them into the pantry in the kitchen.

“There,” he said, dusting off his hands as if ridding himself of something dirty. “This is where you sleep now.” My mother stood behind him, twisting her hands.

I burrowed into the nest of blankets in the kitchen pantry. My book of fairy tales rested on a dusty shelf with the ghostly circles of the canned vegetables we no longer had. After days and then weeks, the beautiful golden firebird on the cover of the book was smeared with grease; on another shelf lay a pile of scrap paper, and my favorite pencil. When I couldn't sleep because of cold or anger, I drew pictures. Drawings of firebirds, a terrible witch named Baba Yaga, houses walking on chicken legs, talking dolls, giants, and wolves with wings.

Their voices rose and fell beyond the pantry door.

“Why can't you see he'd be better off in an orphanage?”

“I can't send him away!”

“You can't afford to feed yourself,” his voice said. “Besides, I don't like him. He's odd.”

“There's nothing wrong with him.”

Glass shattered. “It's him or me, Anya.”

“No! Please don't ask me ⦔

Another crash. The sound of shoving, angry feet on the floor.

“You stupid woman!” A slap.

“Don't!”

A crash. A scream. A thud. A moan.

Quiet.