The Domesticated Brain (9 page)

Read The Domesticated Brain Online

Authors: Bruce Hood

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

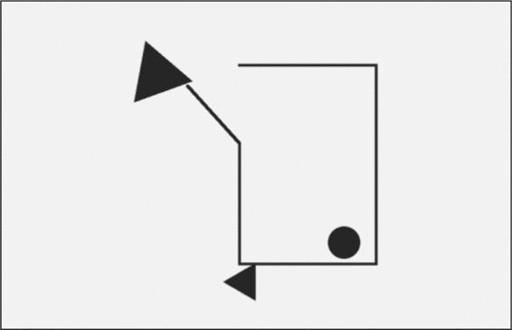

Figure 3: Scene from Heider and Simmel 1944 animation

What is remarkable is that babies even as young as three months of age make exactly the same decisions about the different shapes.

23

They look longer when a shape that has always helped suddenly starts hindering. Already at this age they are attributing good and bad personality characteristics to the shapes.

Are you thinking what I am thinking?

We not only judge others by their deeds but we also try to imagine what is going on in their minds. How do we know what others are thinking? One way is to ask them, but sometimes you cannot use language. On a recent trip to Japan, where I do not speak the language, I discovered just how much I took communication for granted. But before language, there had to be a more primitive form of communication that enabled humans to begin to understand each other.

We had to know that we could share ideas, something that requires an awareness that others have minds and an understanding of what they might be thinking. The real quantum leap in the history of mankind that transformed our species was not initially language, but rather our ability to mind read.

Mind reading

I am going to surprise you with a little mind reading. Take a moment to look over the picture below, Georges de la Tour’s famous painting ‘The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds’ (1635), until you have worked out what is going on.

In all likelihood, your eyes were instinctively drawn to the lady card player at the centre of the picture and, from there, you probably followed her line of gaze to the waitress and then to the faces of the two other players. Eventually you will have spotted the deception. The player on the left is cheating, as we can see that he is taking an ace from behind his back to change his hand into an ace flush of diamonds. He waits for his moment when the other players are not paying attention to him.

How did I know where you would look? Did I read your mind? I did not need to. To fully understand de la Tour’s painting, you have to read the faces and the eyes to work out what is going on in the minds of the players. Studies of the eye movements of adults looking at pictures of individuals in social settings reveal a very consistent and predictable path of scrutiny that speaks volumes about the nature of human interactions.

24

Humans seek out meaning in social

settings by reading others, whereas another animal wandering through the Louvre Museum in Paris where de la Tour’s masterpiece hangs would probably pay little attention to the painting let alone scrutinize the faces for meaning.

Figure 4: ‘The Cheat with the Ace of Diamonds’ by Georges de la Tour (1635)

How do we begin to mind read? We start with the face. Initially we pay attention to the lady at the centre because the face is one of the most important patterns for humans. As adults, we tend to see faces everywhere – in the clouds, on the moon, on the front of VW Beetles. Any pattern with two dots for eyes that has the potential to look like a face is immediately seen as one. It may be a legacy of an adaptive strategy to look out for faces wherever they might be just in case there is a potential enemy hidden in the bushes, or it may simply be that because humans spend so much time looking at faces, we see them everywhere.

25

When we look at faces, we concentrate on the eyes, which explains why this region is responsible for generating the most brain activity in observers.

26

Eyes serve several communicative purposes because they are directed to pick up visual information and, in doing so, reveal when and where someone’s attention is focused. Gaze behaviour is also a precursor to communication, which is why we try to catch someone’s eye before we strike up a conversation. By watching someone else’s eyes, you can work out what is most interesting to them and when it is appropriate to speak. In face to face conversation, the person listening spends roughly twice the amount of time looking at the speaker, who will periodically glance at the listener, especially when they are making an important point or expecting a response.

27

We can gauge how much interest or boredom they are expressing

and whether they have been registering the important messages by watching their gaze behaviour.

Not only do we seek out the gaze of others but it can also be difficult to ignore, especially if they are staring at us. This is why it is hard for soldiers standing to attention on a parade ground to maintain a fixed stare ahead of them when the drill sergeant, only inches away, stares at them and commands ‘Don’t eyeball me, soldier!’ This focus requires a lot of discipline. Mischievous tourists notoriously try to make the guards on sentry duty outside Buckingham Palace lose their concentration by getting the soldier to look at them. Trying to avoid eye contact with someone in front of your face is almost impossible. Likewise, if a speaker you are listening to suddenly looks over your shoulder as if to spot something of interest, then you will automatically turn round to see what has captured their attention. This is because most of us instinctively follow another person’s direction of gaze without even knowing it.

28

Even infants follow eye gaze. When I was at Harvard, I conducted a study where we showed ten-week-old babies an image of a woman’s face on a large computer monitor.

29

She was blinking her eyes open, staring either to the left or right. The babies instinctively looked in the same direction, even though there was often nothing to see.

Gaze monitoring works so well because each human eye is made up of a pupil that opens and constricts to allow varying levels of light into the eye, and a white sclera. This combination of the dark pupil set against the white sclera makes it very easy to work out where someone’s eyes are pointing. Even at a distance, before we can identify who someone is,

we can work out where they are looking. In a sea of faces, we are quickest to spot the face whose eyes are directed at us.

30

Direct staring, especially if prolonged, triggers the emotional centres of the brain, including the amygdalae, which are associated with the four Fs.

31

If the other person is someone you like, the experience can be pleasing, but it is distressing if they are a stranger. Newborns prefer faces with a direct gaze

32

and, as we saw earlier, if you engage with a three-month-old baby by looking at them, they will smile back at you.

33

However, as children develop, patterns of gaze behaviour change because there are cultural differences in what is regarded as acceptable behaviour.

Cultural norms explain why staring at strangers is common in many Mediterranean countries, but makes foreign tourists often feel uncomfortable at being gawked at when on holiday.

34

Likewise, direct eye contact, especially between someone of lower status with someone of higher status such as a student and teacher in Japanese culture, is not considered polite. Japanese adults perceive direct gaze as angrier, unapproachable and more unpleasant.

35

Whereas in the West, we tend to think of someone who does not look you in the eye during a conversation as being shifty and deceitful.

When individuals from different cultures with different social norms get together, it can be an uncomfortable exchange as each tries to establish or avoid eye contact. This cultural variation shows that paying attention to another’s gaze is a universal behaviour programmed into our brains at birth, but it is shaped by social norms over the course of our childhood. Our culture defines what are considered

appropriate and inappropriate social interactions, influencing our behaviour through emotional regulation of what feels right when we communicate.

Mind games

By signalling the focus of another’s interest, gaze monitoring enables humans to engage in joint attention. How many times have you been in the company of a bore at a party who is droning on and you want to leave with your partner or friend but cannot tell them directly? A roll of the eyes, raised eyebrows and a nod of the head towards the door are all effective non-verbal cues. Even if the other person is a stranger or does not speak your language, you would be able to understand each other without exchanging a word. Joint attention is the capacity to direct another’s interest towards something notable. It is a reciprocal behaviour; you pay attention to what I am focused on and, in return, I pay attention to you. When two individuals are engaged in joint attention, they are monitoring each other in a cooperative act to attend to things of interest in the world.

Other animals, such as meerkats, can direct attention by turning their heads to signal a potential threat. Gorillas interpret direct gaze as a threat, which is why there is a sign at my local Bristol zoo where Jock the 34 stone 6 foot silverback male lives telling visitors not to stare at him. Jock pays attention to gaze as a source of threat, but we are the only species that has the capacity to read the meaning of the eyes over and beyond sex and violence (domesticated dogs being the notable exception that we described in the opening to the

book). We use other people’s gaze to interpret the nature of relationships. People who know each other exchange glances and those in love stare at each other.

36

This explains those awkward moments that we have all had when we exchange a glance or stare with a stranger in the street or, worse, in an elevator where it is difficult to walk away. Do I know you? Or do you want to be friendly or fight? At a party we can look around and work out who likes each other just by monitoring patterns of joint attention. This ability to work out ‘who likes who’ based on gaze alone develops as we become more socially adept. Six-year-olds can identify who are friends based on synchronized mutual gaze, but younger children find it difficult.

37

Joint attention in younger children and babies is really just from the child’s own perspective. If it does not involve them, then they are not bothered. As children become socially more skilled at interacting with others, they start to read others for information that is useful for becoming part of the group.

Joint attention may have evolved as a means to signal important events out in the world in the same way that meerkats use it, but we have developed gaze monitoring into a uniquely human capacity to share interests that enable us to cooperate and work together. No other animal spends as much time engaged in mutual staring and joint attention as humans.

Gaze monitoring is also one of the basic building blocks for social cooperation. We are much more likely to conform to rules and norms if we believe that we are being watched by others. A poster with a pair of eyes reminiscent of George Orwell’s ‘Big Brother’ makes people tidy up after themselves,

follow garbage separation rules, voluntarily pay for beverages and give half as much again to charity boxes left in supermarkets.

38

Even though individuals may be totally alone, just the thought that they might be watched is enough to get most people to act on their best behaviour. Other people’s gaze makes us become more self-conscious, prosocial and likely to conform.

It is notable that humans are the only primate out of the 200-plus species who have a sclera enlarged enough to make gaze monitoring so easy for us. In humans, the sclera is three times larger than that of any other non-human primate. If you think about it, evolution of the human sclera could not have been for the benefit of the individual alone. There would have been no selective advantage for me with my big white sclera unless there was someone else around to read my eyes. Rather, it had to be of mutual benefit to those who can read my eyes as well as myself.

39

It is only of use within a group that learns to watch each other for information.