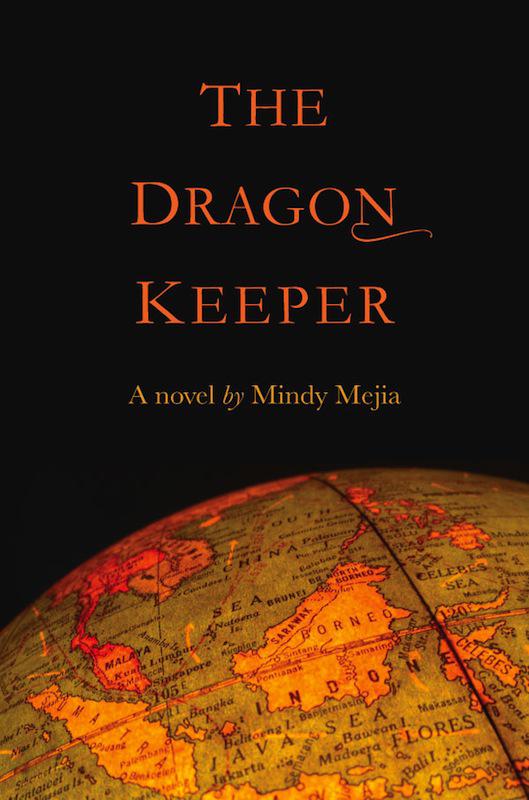

The Dragon Keeper

The Dragon Keeper

a novel by

Mindy Mejia

The Dragon Keeper

A novel by Mindy Mejia

Published by Ashland Creek Press

© 2012 Mindy Mejia

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-61822-013-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012931269

This is a work of fiction. All characters and scenarios appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cover and book design by John Yunker.

For Andy—the composer, midnight painter,

hyperbole weaver, star chart reader,

fallen soldier

and my oldest friend.

The Dayaks of Borneo worshipped Jata, the Watersnake goddess.

Together with the Hornbill, Mahatala,

she destroyed the Tree of Life and created the world.

— from

Ngaju Religion: The Conception of God Among a South Borneo People

by Hans Scharer

Hatching Day

M

eg Yancy kept a picture to remind herself where she and Jata began. The picture wasn’t of either one of them; it was of the history of the relationship between Komodo dragons and humans.

Only a hundred years ago, the first white men started sailing the Indian and Pacific Oceans to Komodo Island in search of the dragons. They called themselves adventurers, without any irony, and they were on a King Kong mission to capture the biggest lizards in the world. Zoos all over Europe and America had just heard of the Komodo dragon, and everyone wanted a piece of the action, all of them trying to outbid one another for the first exhibit in the Western hemisphere. In other words, it was the typical feeding frenzy Meg always read about whenever some new, crazy species splashed onto the pages of the trade journals.

What made this story different was that the Komodo kings—those much-hyped, little-understood predators—didn’t go quietly into that dark cage. They beat the men who hunted them, and no one saw it coming.

When the men landed on the island, the dragons didn’t attack them. Despite what recent headlines suggest, Komodos don’t regularly eat people. Humans taste bad—ask any shark. The dragons didn’t run or hide either; it wouldn’t even occur to a ten-foot-long, three-hundred-pound dragon to hide from some smelly, chattering mammals.

The men baited them with bleeding goats, trapped them, made the local villagers bind their jaws and legs, and measured them to make sure they were the longest, most impressive specimens to send back to the Western zoos. They loaded the dragons in wooden cages onto their ships, then kicked back in their cabins, sipping whiskey, polishing their guns—totally oblivious to what happened next.

The dragons broke free.

They smashed their cages to boards and splinters, ran past the shocked crew up the stairs to the main deck, and jumped, leaping overboard with a splash that must have sounded like “No fucking thank you,” and dove through the dark waters to swim home.

They couldn’t have made it. The dragons had escaped in the middle of the ocean with no land in sight. All of them died of hypothermia or sheer exhaustion, but Meg knew that wasn’t the point. The point was that they died free. They died unbeaten.

Eventually the humans got smarter and found ways to contain the animals during the long trip and deliver them to all the zoos. Jata’s ancestors were among the captured ones. Now, as a keeper, Meg tried to make the cage bearable for the ones who weren’t lucky enough to escape and die free.

As she opened the outer door to the Komodo dragon exhibit at the Zoo of America and walked inside, Meg went straight to the picture she kept taped up on the wall. It was from around 1910, as near as she could figure, and it was a snapshot of one of the first Komodos in an American zoo. The dragon sat in a small, metal enclosure with no food, no water, and no chance for escape. After weeks at sea, that bare cage was his final destination. It was a hopeless picture, the kind that always made Meg mad, until she turned to the main exhibit door and saw what a hundred years could do.

Through the viewing window, Meg could glimpse a sliver of the ten-foot rock wall that circled the habitat. A large swimming pond took up the far side of the space, and various trees and shrubs dotted the sandy ground. Two large, flat boulders were powered with internal heaters to keep their surfaces toasty warm, perfect for afternoon basking. The area even boasted a cave for some privacy. At five hundred square feet, the exhibit was bigger than Meg’s first college apartment. It was exactly the kind of environment that a Komodo dragon should live in, if it had to live in a zoo—except today Meg’s job was to get that dragon out.

She unlocked and opened a window on the holding room’s restraint box—which was basically a reinforced coffin with airholes—and dropped in the backside of a chicken, minus some feathers and guts. Re-locking the window, she walked to the other end of the box and lifted a steel lever attached to the wall. A low, creaking motion inside the wall signaled that the door had opened, connecting the exhibit to the restraint box. Curtain up. She paced back to the main exhibit door and lifted herself up to her toes to peer through the lead glass. The metal cooled a circle into her stomach through the uniform, and her breath fogged the window. One second, two. There was no reason to step inside to call her when the chicken would do all the work. Komodos could smell carrion two miles across the Indonesian savannah; a forty-foot distance would be like shoving a piping hot pizza in Jata’s face.

The pool and basking rocks were empty, so Meg focused on the cave, which wasn’t really a cave. The rock outcropping that supported the visitor’s viewing platform hovered over the exhibit a couple feet above the dirt floor. It was a crevice, if anything, just a thin, black cavity tucked underneath the constant stream of visitors.

That’s where Jata appeared.

At first she was just a bust, some kind of sculpture made out of copper running to green. Her square snout protruded out from the shadows, and she tasted the air with a flick of forked yellow, confirming what had woken her from her nap. Chicken. It flashed from her tongue to her eyes, which darted immediately to where the mini-door opened into the restraint box. Climbing out of the cave in two giant lunges, Jata broke into the open space in dead pursuit of a free lunch.

This was the best part, watching Jata walk. Did those European explorers feel the same awe when they caught their first glimpse of a Komodo dragon? Jata walked diagonally, one foot in time with the opposite hind leg, in a sweeping, swaggering motion. Her tail pumped out behind her like a three-foot-long, bone-encrusted rudder, stirring up dirt and leaves and even a few wadded-up napkins in her wake. Sweep, swagger, she walked. Sweep, swagger, and even though her head bobbed up and down in time, her eyes never moved; they had locked in on the restraint-box door. She passed underneath Meg’s window and out of sight, and then from inside the box came the clicking of claws on wood, the rustle and brush of scales against the walls, and, finally, after a beat, the juicy rip of chicken. Meg slammed the lever down. She had to be quick. Even sleepy, Jata liked to grab the bait and wriggle back out before she was trapped.

There was a thump in the box near her ankle, a disgruntled tail.

“Sorry, sweetheart, but this won’t take long.” Patting the box near an airhole, Meg picked up a flashlight and a shovel and let herself into the exhibit.

The few visitors strolling down the Reptile Kingdom path cocked their heads and waited to see if Meg would do anything interesting. Behind bars, humans were just as fascinating as animals. Without breaking stride, Meg scooped up the napkins and chucked them up into the walkway. At least napkins were biodegradable. Freaking people used the turtle pond as a wishing well, and then they had to do surgery to pull $1.85 out of the turtle’s stomach. The visitors, a couple of teenagers holding hands, rolled their eyes and kept walking to the exit. No one else appeared around either corner of the path, so after a quick double-check of the keeper’s entrance to make sure the coast was clear, Meg clicked off the radio on her belt, turned on the flashlight, and wriggled into the cave.

As a juvenile, Jata had scampered in and out of this place freely, but as the years passed and she grew to more than six feet long and 180 pounds’ worth of scale and muscle, the cave became a tight fit, and she’d started burrowing. At first, Meg hadn’t even realized it—the whole place was so hidden—but then the dirt started mounding up at the sides of the rock, along with all the loose bits of gravel and sand, just like an avalanche waiting to happen. It was natural enough for a Komodo to make a burrow. They used them to conserve heat and sometimes slept in them, but tunneling wasn’t exactly one of their best skills, and every once in a while on Komodo Island someone came across a dead dragon that had suffocated under the weight of its own ingenuity.

Meg crawled into the cave, military-style, and began packing the top layers of dirt back with the shovel so the walls flowed down to the floor in an easy slope, eliminating any chance of a cave-in. It was quiet work, not too bad for anyone who didn’t get that buried-alive nightmare. From here, it was hard even to hear the humming of the building generators. The world shrank down to just the dull thwacks of the shovel, the smell of mossy soil, and the sweet curl of sweat trailing from her temples to the corners of her mouth. She worked her way around the cement circle and was checking the perimeter one last time when something broke the silence.

“Yancy!” The voice was distorted and distant. She switched the flashlight off.

“Yancy, I know you’re in there. I can see your keys on the ground.”

Shit. She must have dropped them before crawling inside. The voice was male but definitely not her boss. It had more

oomph

than anything Chuck could belt out.

There was just enough room to scoot around so she didn’t have to back out ass first. After she inched back out into the exhibit on her elbows and knees, the light burned her eyes. She paused at the exact spot where Jata had stopped earlier—head out, considering and wary.

“What the hell are you doing under there? I didn’t even know that was open space.”

Antonio Rodríguez’s voice came from directly above her, so she flipped to her back and leaned on her elbows. Ten feet of rock, concrete, and steel towered over her, a bumpy landscape that seemed to stretch all the way into the white beams of the roof, except for the round splotch breaking the horizon of the railing like a black sun. Antonio was just a silhouette, totally eclipsed by the light streaming in from the arching skylights.

“Yeah, it’s open under here. Is that all?”

“You look like a prairie dog.”

Dirt sifted out of her hair and landed on her nose as she shrugged, but she bit down on the sneeze. No need to hand him any more satisfaction.

“You playing tourist today, Rodríguez? What do you want?”

“Don’t you have someone watching your back under there? Or a safety harness or something?”

She pulled herself the rest of the way out of the cave and stood up, arms crossed. Antonio was the head veterinarian, a tall, dark, handsome pain in the ass. When he wasn’t working his Latin heartthrob angle on some hapless intern, he was using the zoo as his personal laboratory to grab as much industry attention as his endless studies could get. Now, lounging over the railing, he looked as if it were Sunday afternoon at the horse track and he had a winning ticket tucked in his front pocket. He grinned, flashing teeth that were whiter than his lab coat. He knew he’d caught her, the bastard.