The Dumbest Generation (18 page)

Read The Dumbest Generation Online

Authors: Mark Bauerlein

Given the enormous sums of money at stake, and the backing of the highest political and business leaders, these discouraging developments should enter the marketplace of debate over digital learning. They are not final, of course, but they are large and objective enough to pose serious questions about digital learning. The authors of the studies aren’t Luddites, nor are school administrators anti-technology. They observe standards of scientific method, and care about objective outcomes. Their conclusions should, at least, check the headlong dash to technologize education.

All too often, however, the disappointment veers toward other, circumstantial factors in the execution, for instance, insufficient usage by the students and inadequate preparation of the teachers. In the 2006

ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Technology,

when researchers found that most of the younger respondents and female respondents wanted less technology in the classroom, not more, they could only infer that those students “are comparatively unskilled in IT to support academic purposes.” It didn’t occur to them that those students might have decent IT skills and still find the screen a distraction. Several education researchers and commentators have mistrusted technophilic approaches to the classroom, including Larry Cuban, Jane Healy, and Clifford Stoll, but their basic query of whether computers really produce better intellectual results is disregarded. On the tenth anniversary of E-Rate, for instance, U.S. senators proposed a bill to strengthen the program while tightening performance measures—but they restricted the tightening to financial and bureaucratic measures only, leaving out the sole proper justification for the costs, academic measures. The basic question of whether technology might, under certain conditions, hinder academic achievement goes unasked. The spotlight remains on the promise, the potential. The outcomes continue to frustrate expectations, but the backers push forward, the next time armed with an updated eBook, tutelary games the kids will love, more school-wide coordination, a 16-point plan, not a 15-point one . . . Ever optimistic, techno-cheerleaders view the digital learning experience through their own motivated eyes, and they picture something that doesn’t yet exist: classrooms illuminating the wide, wide world, teachers becoming twenty-first-century techno-facilitators, and students at screens inspired to ponder, imagine, reflect, analyze, memorize, recite, and create.

ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Technology,

when researchers found that most of the younger respondents and female respondents wanted less technology in the classroom, not more, they could only infer that those students “are comparatively unskilled in IT to support academic purposes.” It didn’t occur to them that those students might have decent IT skills and still find the screen a distraction. Several education researchers and commentators have mistrusted technophilic approaches to the classroom, including Larry Cuban, Jane Healy, and Clifford Stoll, but their basic query of whether computers really produce better intellectual results is disregarded. On the tenth anniversary of E-Rate, for instance, U.S. senators proposed a bill to strengthen the program while tightening performance measures—but they restricted the tightening to financial and bureaucratic measures only, leaving out the sole proper justification for the costs, academic measures. The basic question of whether technology might, under certain conditions, hinder academic achievement goes unasked. The spotlight remains on the promise, the potential. The outcomes continue to frustrate expectations, but the backers push forward, the next time armed with an updated eBook, tutelary games the kids will love, more school-wide coordination, a 16-point plan, not a 15-point one . . . Ever optimistic, techno-cheerleaders view the digital learning experience through their own motivated eyes, and they picture something that doesn’t yet exist: classrooms illuminating the wide, wide world, teachers becoming twenty-first-century techno-facilitators, and students at screens inspired to ponder, imagine, reflect, analyze, memorize, recite, and create.

They do not pause to consider that screen experience may contain factors that cannot be overcome by better tools and better implementation. This is the possibility that digital enthusiasts must face before they peddle any more books on screen intelligence or commit $15 million to another classroom initiative. Techno-pushers hail digital learning, and they like to talk of screen time as a heightened “experience,” but while they expound the features of the latest games and software in detail, they tend to flatten and overlook the basic features of the most important element in the process, the young persons having the experiences. Digital natives are a restless group, and like all teens and young adults they are self-assertive and insecure, living in the moment but worrying over their future, crafting elaborate e-profiles but stumbling through class assignments, absorbing the minutiae of youth culture and ignoring works of high culture, heeding this season’s movie and game releases as monumental events while blinking at the mention of the Holocaust, the Cold War, or the War on Terror. It is time to examine clear-sightedly how their worse dispositions play out online, or in a game, or on a blog, or with the remote, the cell phone, or the handheld, and to recognize that their engagement with technology actually aggravates a few key and troubling tendencies. One of those problems, in fact, broaches precisely one of the basics of learning: the acquisition of language.

WHEN RESEARCHERS, educators, philanthropists, and politicians propose and debate adjustments to education in the United States, they emphasize on-campus reforms such as a more multicultural curriculum, better technology, smaller class size, and so on. At the same time, however, the more thoughtful and observant ones among them recognize a critical but outlying factor: much of the preparation work needed for academic achievement takes place not on school grounds but in informal settings such as a favorite reading spot at home, discussions during dinner, or kids playing Risk or chess. This is especially so in the nontechnical, nonmathematical areas, fields in which access to knowledge and skill comes primarily through reading. Put simply, for students to earn good grades and test scores in history, English, civics, and other liberal arts, they need the vocabulary to handle them. They need to read their way into and through the subjects, which means that they need sufficient reading-comprehension skills to do so, especially vocabulary knowledge. And the habits that produce those skills originate mostly in their personal lives, at home and with friends, not with their teachers.

Everything depends on the oral and written language the infant-toddler -child-teen hears and reads throughout the day, for the amount of vocabulary learned inside the fifth-grade classroom alone doesn’t come close to the amount needed to understand fifth-grade textbooks. They need a social life and a home life that deliver requisite words to them, put them into practice, and coax kids to speak them. Every elementary school teacher notices the results. A child who comes into class with a relatively strong storehouse of words races through the homework and assembles a fair response, while a child without one struggles to get past the first paragraph. No teacher has the time to cover all the unknown words for each student, for the repository grows only after several years of engagement in the children’s daily lives, and the teacher can correct only so much of what happens in the 60+ waking hours per week elsewhere. That long foreground, too, has a firm long-term consequence. The strong vocabulary student learns the new and unusual words in the assigned reading that he doesn’t already know, so that his initial competence fosters even higher competence. The weak vocabulary student flails with more basic words, skips the harder ones, and ends up hating to read. For him, it’s a pernicious feedback loop, and it only worsens as he moves from grade to grade and the readings get harder.

The things they hear from their parents, or overhear; the books and magazines they read; the conversation of their playmates and fellow students; the discourse of television, text messages, music lyrics, games, Web sites . . . they make up the ingredients of language acquisition. It is all too easy to regard out-of-school time only as a realm of fun and imagination, sibling duties and household chores, but the language a child soaks up in those work and play moments lays the foundation for in-school labor from kindergarten through high school and beyond. And so, just as we evaluate schools and teachers every year, producing prodigious piles of data on test scores, funding, retention, and AP course-taking, we should appraise the verbal media in private zones too. Which consumptions build vocabulary most effectively?

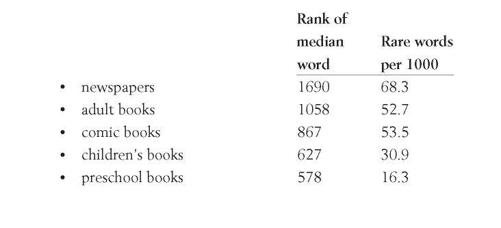

We can’t follow children around and record the words they hear and read, but we can, in fact, empirically measure the vocabulary of the different media children and teens encounter. The discrepancies are surprising. One criterion researchers use is the rate of “rare words” in spoken and written discourse. They define “rare words” as words that do not rank in the top 10,000 in terms of frequency of usage. With the rare-word scale, researchers can examine various media for the number of rare words per thousand, as well as the median-word ranking for each medium as a whole.

The conclusions are nicely summarized in “What Reading Does for the Mind” by education psychologists Anne E. Cunningham and Keith E. Stanovich, who announce straight off, “What is immediately apparent is how lexically impoverished most speech is compared to written language.” Indeed, the vocabulary gap between speech and print is clear and wide. Here is a chart derived from a 1988 study showing the rare-word breakdown for print materials.

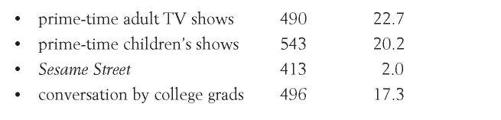

And the same for oral materials.

Print far exceeds live and televised speech, even to the point that a book by Dr. Seuss falls only slightly beneath the conversation of intelligent adults on the rare-word-per-thousand scale. And when compared to a television show for the same ages,

Sesame Street,

preschool books outdo it by a hefty factor of eight. Adult books more than double the usage of rare words in adult TV shows, and children’s books beat them on the median-word ranking by 137 slots. Surprisingly, cartoons score the highest vocabulary of television speech. (I do recall the voice of Foghorn Leghorn as more lyrical and the discourse of Mr. Peabody more intellectual than anything from Rachel and Monica or Captain Frank Furillo.)

Sesame Street,

preschool books outdo it by a hefty factor of eight. Adult books more than double the usage of rare words in adult TV shows, and children’s books beat them on the median-word ranking by 137 slots. Surprisingly, cartoons score the highest vocabulary of television speech. (I do recall the voice of Foghorn Leghorn as more lyrical and the discourse of Mr. Peabody more intellectual than anything from Rachel and Monica or Captain Frank Furillo.)

The incidence of rare words is a minute quantitative sum, but it signifies a crucial process in the formation of intelligent minds. Because a child’s vocabulary grows mainly through informal exposure, not deliberate study, the more words in the exposure that the child doesn’t know, the greater the chances for growth—as long as there aren’t too many. If someone is accustomed to language with median-word ranking at 1,690 (the newspaper tally), a medium with a median-word ranking of 500 won’t much help.Young adults can easily assimilate a discourse whose every word is familiar. While that discourse may contain edifying information, it doesn’t help them assimilate a more verbally sophisticated discourse next time. Exposure to progressively more rare words expands the verbal reservoir. Exposure to media with entirely common words keeps the reservoir at existing levels.

Years of consumption of low rare-word media, then, have a dire intellectual effect. A low-reading, high-viewing childhood and adolescence prevent a person from handling relatively complicated texts, not just professional discourses but civic and cultural media such as the

New York Review of Books

and the

National Review.

The vocabulary is too exotic. A child who reads children’s books encounters 50 percent more rare words than a child who watches children’s shows—a massive discrepancy as the years pass. Indeed, by the time children enter kindergarten, the inequity can be large and permanent. Education researchers have found that children raised in print-heavy households and those raised in print-poor households can arrive at school with gaps in their word inventories of several thousand. Classroom life for low-end kids ends up an exercise in pain, like an overweight guy joining a marathon team and agonizing through the practice drills. It doesn’t work, and the gap only grows over time as failure leads to despair, and despair leads to estrangement from all academic toil. A solitary teacher can do little to change their fate.

New York Review of Books

and the

National Review.

The vocabulary is too exotic. A child who reads children’s books encounters 50 percent more rare words than a child who watches children’s shows—a massive discrepancy as the years pass. Indeed, by the time children enter kindergarten, the inequity can be large and permanent. Education researchers have found that children raised in print-heavy households and those raised in print-poor households can arrive at school with gaps in their word inventories of several thousand. Classroom life for low-end kids ends up an exercise in pain, like an overweight guy joining a marathon team and agonizing through the practice drills. It doesn’t work, and the gap only grows over time as failure leads to despair, and despair leads to estrangement from all academic toil. A solitary teacher can do little to change their fate.

This is why it is so irresponsible for votaries of screen media to make intelligence-creating claims. Even if we grant that visual media cultivate a type of spatial intelligence, they still minimize verbal intelligence, providing too little stimulation for it, and intense, long-term immersion in it stultifies the verbal skills of viewers and disqualifies them from most every academic and professional labor. Enthusiasts such as Steven Johnson praise the decision-making value of games, but they say nothing about games implanting the verbal tools to make real decisions in real worlds. William Strauss and Neil Howe, authors of

Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation

(2000), claim that the Millennial Generation (born after 1981) is optimistic, responsible, ambitious, and smart, and that, partly because of their “fascination for, and mastery of, new technologies,” they will produce a cultural renaissance with “seismic consequences for America.” But Strauss and Howe ignore the lexical poverty of these new technologies, and they overlook all the data on the millennials’ verbal ineptitude. Unless they can show that games and shows and videos and social networking sites impart a lot more verbal understanding than a quick taste of

Grand Theft Auto

and

Fear Factor

and

MySpace

reveals, sanguine faith in the learning effects of screen media should dissolve.

Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation

(2000), claim that the Millennial Generation (born after 1981) is optimistic, responsible, ambitious, and smart, and that, partly because of their “fascination for, and mastery of, new technologies,” they will produce a cultural renaissance with “seismic consequences for America.” But Strauss and Howe ignore the lexical poverty of these new technologies, and they overlook all the data on the millennials’ verbal ineptitude. Unless they can show that games and shows and videos and social networking sites impart a lot more verbal understanding than a quick taste of

Grand Theft Auto

and

Fear Factor

and

MySpace

reveals, sanguine faith in the learning effects of screen media should dissolve.

Other books

Blind Beauty by K. M. Peyton

Mr. Black's Proposal by Aubrey Dark

See Me by Higgins, Wendy

Death on Account (The Lakeland Murders) by Salkeld, J J

Mystery of the Midnight Rider by Carolyn Keene

Long Drive Home by Will Allison

Long Slow Second Look by Marilyn Lee

The Immortalists by Kyle Mills

Awakened by Cast, P. C.

Kill Fee by Barbara Paul