The Egypt Code (41 page)

Authors: Robert Bauval

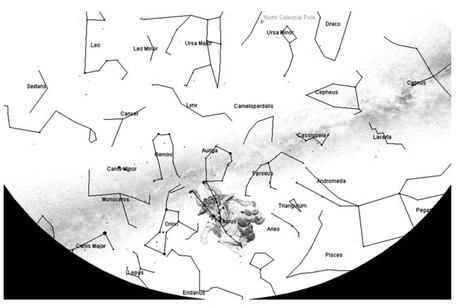

Fig. 9

Portion of the sky at the latitude of Copenhagen, in 2000 BC.

Portion of the sky at the latitude of Copenhagen, in 2000 BC.

Unfortunately, we do not know the level of astronomical knowledge of the Celtic astronomers, because most of the information we have on them comes from secondary sources, especially (curiously indeed) from the stoic Hellenistic writer Posidonio, besides the Roman sources like Caesar’s writings. However, some primary information is available, like e.g. the

Coligny Calendar

, a lunar calendar written in Roman characters but in the Gallic language. In addition, the lore of astronomy in Bronze Age in North Europe has still to reveal his secrets, as shows the recent discovery of the so called Nebra Disk, a 16th century BC Bronze disk showing 32 stars, a crescent and the sun and probably representing a particular sky on a particular day.

Coligny Calendar

, a lunar calendar written in Roman characters but in the Gallic language. In addition, the lore of astronomy in Bronze Age in North Europe has still to reveal his secrets, as shows the recent discovery of the so called Nebra Disk, a 16th century BC Bronze disk showing 32 stars, a crescent and the sun and probably representing a particular sky on a particular day.

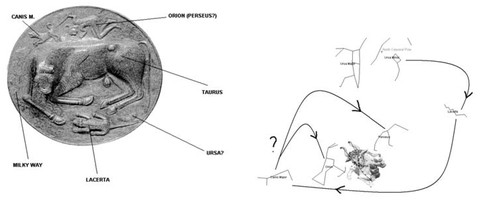

Fig. 10

The central plaque of the Gundestrup cauldron and the corresponding

astronomical interpretation. The picture on the right is the same as that in

Fig. 9

, with

only the relevant constellations shown. Reading in clockwise direction in a spiral from

the pole (Ursa) we find Lacerta, Canis Major, Orion (actually Perseus if one has to

proceed on the spiral) and Taurus.

The central plaque of the Gundestrup cauldron and the corresponding

astronomical interpretation. The picture on the right is the same as that in

Fig. 9

, with

only the relevant constellations shown. Reading in clockwise direction in a spiral from

the pole (Ursa) we find Lacerta, Canis Major, Orion (actually Perseus if one has to

proceed on the spiral) and Taurus.

In any case, it is again difficult to believe (at least to me) that also the Celts did rapidly filtrate the discovery by Hipparchus, in such a way that an artist of the first century BC decided to represent a precessional event occurring 2000 years before in his masterpiece.

5 Concluding RemarksAll in all, there is

no

clear, absolute evidence of the discovery of precession before Hellenistic times or in pre-Columbian culture. There is, however, at least in my view, a clear evidence that simple astronomical phenomena, such as heliacal rising of bright stars or the movement of the equinoctial point through zodiacal constellations were traced for a sufficient amount of time and with a sufficient precision to lead many ancient astronomers to the discovery that ‘something was happening’ with a very slow velocity with respect to human life.

no

clear, absolute evidence of the discovery of precession before Hellenistic times or in pre-Columbian culture. There is, however, at least in my view, a clear evidence that simple astronomical phenomena, such as heliacal rising of bright stars or the movement of the equinoctial point through zodiacal constellations were traced for a sufficient amount of time and with a sufficient precision to lead many ancient astronomers to the discovery that ‘something was happening’ with a very slow velocity with respect to human life.

More research focussed on this issue is certainly needed, first of all in Egypt. In fact, the problem of the stellar alignment of Egyptian temples should be reconsidered taking into account that the chronology of Egypt is much more clear and accurate than it was in Lockyer times, and controlling the assertions of Lockyer from a

quantitative

point of view (for instance following the subsequent enlargements of the Luxor temple in terms of precessional movement of the stars). Theoretical research is also needed to relate in a secure way decanal lists coming from different centuries.

quantitative

point of view (for instance following the subsequent enlargements of the Luxor temple in terms of precessional movement of the stars). Theoretical research is also needed to relate in a secure way decanal lists coming from different centuries.

The need for further research holds true also in Malta, and in all the places which show an interest of the builders for alignments changing in time due to precession.

ReferencesAlbrecht, K. (2001),

Maltas Tempel: Zwischen Religion und Astronomie

, Naether-Verlag, Potsdam.

Maltas Tempel: Zwischen Religion und Astronomie

, Naether-Verlag, Potsdam.

Aveni, A. F. (2001),

Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico

, University of Texas Press, Austin.

Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico

, University of Texas Press, Austin.

Aveni, A. F and Gibbs, S. L. (1976), ‘On the orientation of pre-Columbian buildings in central Mexico’,

American Antiquity

, Vol. 41, pp. 510-17.

American Antiquity

, Vol. 41, pp. 510-17.

Badawy, A. (1964), ‘The stellar destiny of pharaoh and the so called air shafts in Cheops pyramid’,

M.I.O.A.W.B

. Band 10, p.189.

M.I.O.A.W.B

. Band 10, p.189.

Bauval, R. (1993), ‘Cheop’s pyramid: a new dating using the latest astronomical data’,

Discussions in Egyptology

. Vol. 26, p.5.

Discussions in Egyptology

. Vol. 26, p.5.

Belmonte, J.A. (2001a), ‘The Ramesside star clocks and the ancient egyptian constellations

’, SEAC

Conference on Symbols, calendars and orientations, Stockholm.

’, SEAC

Conference on Symbols, calendars and orientations, Stockholm.

Belmonte, J.A. (2001b), ‘The decans and the ancient Egyptian skylore: an astronomer’s approach’

, INSAP III Meeting

, Palermo.

, INSAP III Meeting

, Palermo.

Belmonte, J.A. (2001c), ‘On the orientation of Old Kingdom Egyptian Pyramids’,

Archaeoastronomy

26, 2001, S1.

Archaeoastronomy

26, 2001, S1.

De Santillana, G.,Von Dechend, E.(1983),

Hamlet’s Mill

, Dover Publications.

Hamlet’s Mill

, Dover Publications.

Dow, J. (1967), ‘Astronomical orientations at Teotihuacan; A case study in astroarchaeology’,

American Antiquity

, Vol. 32, pp. 326-34.

American Antiquity

, Vol. 32, pp. 326-34.

Feuerstein, G., Kak, S., and Frawley, D. (1995),

In search of the cradle of civilization

, Wheaton, Quest Books.

In search of the cradle of civilization

, Wheaton, Quest Books.

Eddy, J. A. (1974), ‘Astronomical alignment of the Big Horn Medicine Wheel’,

Science.

Vol 18, p.1035.

Science.

Vol 18, p.1035.

Eddy, J. A. (1977), ‘Medicine wheels and plains Indian astronomy’. In Aveni, A. (ed.),

Native American Astronomy

, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 147-70.

Native American Astronomy

, University of Texas Press, Austin, pp. 147-70.

Haack, S. (1984), ‘The astronomical orientation of the Egyptian pyramids’,

Archeoastronomy

, Vol. 7, S119.

Archeoastronomy

, Vol. 7, S119.

Hoskin, M. (2001),

Tombs, temples and their orientations,

Ocarina books.

Tombs, temples and their orientations,

Ocarina books.

Kak, S. (2000), ‘Birth and Early Development of Indian Astronomy’. In

Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy

, Helaine Selin (ed), Kluwer, pp. 303-40.

Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy

, Helaine Selin (ed), Kluwer, pp. 303-40.

Krupp, E. C. (1983),

Echoes of the Ancient Skies

, Harper, New York.

Echoes of the Ancient Skies

, Harper, New York.

Krupp, E.C. (1988), ‘The light in the temples’. In Ruggles C.L.N. (ed.)

Records In Stone: Papers In Memory Of Alexander Thom

, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Records In Stone: Papers In Memory Of Alexander Thom

, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lockyer, N. (1894),

The Dawn of Astronomy

.

The Dawn of Astronomy

.

Magli, G. (2003),

On the astronomical orientation of the IV dynasty Egyptian pyramids and the dating of the second Giza pyramid

(preprint)

On the astronomical orientation of the IV dynasty Egyptian pyramids and the dating of the second Giza pyramid

(preprint)

Mathieu, B. (2001), ‘Travaux de l’Institut Francais d’Archeologie Orientale en 2-2001’, BIFAO, p. 101.

Neugebauer, O. (1976),

A History of ancient mathematical astronomy,

Springer-Verlag.

A History of ancient mathematical astronomy,

Springer-Verlag.

Neugebauer

,

O (1969),

The exact sciences in antiquity

Dover Publications, New York .

,

O (1969),

The exact sciences in antiquity

Dover Publications, New York .

Neugebauer, O, Parker, R.A.(1964),

Egyptian Astronomical Texts,

Lund Humphries, London.

Egyptian Astronomical Texts,

Lund Humphries, London.

Pettinato, G. (1998),

La scrittura celeste

, Milano, Mondadori.

La scrittura celeste

, Milano, Mondadori.

Pogo, A. (1930), The astronomical ceiling decoration of the tomb of Semnut,

ISIS

, Vol. 14, p. 301.

ISIS

, Vol. 14, p. 301.

Rappenglueck, M. (1998), ‘Palaeolithic Shamanistic Cosmography: How is the Famous Rock Picture in the Shaft of the Lascaux Grotto to be Decoded?’, XVI Valcamonica Symposium Arte Preistorica e Tribale, Sciamanismo e Mito.

Robinson, J.H.(1980). ‘Fomalhaut and Cairn D at the Big Horn and Moose Mountain Medicine Wheels’,

Archaeaoastronomy: Bull. Center for Archaeoastr.,

pp.15-9.

Archaeaoastronomy: Bull. Center for Archaeoastr.,

pp.15-9.

Spence, K. (1999), ‘Ancient Egyptian chronology and the astronomical orientation of pyramids’,

Nature

, Vol. 408, p.320.

Nature

, Vol. 408, p.320.

Trimble,V. (1964),

‘Astronomical investigations concerning the so called air shafts of Cheops pyramid’, M.I.O.A.W.B.,

Band 10, p. 183.

‘Astronomical investigations concerning the so called air shafts of Cheops pyramid’, M.I.O.A.W.B.,

Band 10, p. 183.

Trump, D. H. (1991),

Malta: An Archaeological Guide

, Progress Press Co. Ltd.

Malta: An Archaeological Guide

, Progress Press Co. Ltd.

Trump, D.H. (2002),

Malta: Prehistory and Temples

, Midsea Books.

Malta: Prehistory and Temples

, Midsea Books.

Ulansey, D. (1989

), The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries

, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

), The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries

, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Verdier, P. (2000) L’Astronomie celtique : l’énigme du chaudron de Gun-destrup, Archéologue 6.

Zaba, Z. (1953),

L’orientation astronomique dans l’ancienne Egypte et la precession de l’axe du monde

, Prague, 1953.

L’orientation astronomique dans l’ancienne Egypte et la precession de l’axe du monde

, Prague, 1953.

APPENDIX 3

An Overview of the Orion Correlation Theory (OCT): Was the angle of observation 52.2 degrees south of east?

By Chris Tedder

The following article has been published by Chris Tedder and is here reproduced with his kind permission in full and without any alteration.

BackgroundIn 1983, Robert Bauval noticed the similarity between the three-star asterism in Orion, and the site layout of the three pyramid complexes on the Giza plateau. This observation became the core idea of the Orion Correlation Theory (OCT). Following a recommendation by Dr Edwards, Robert Bauval’s paper, ‘A Master Plan for the Three Pyramids of Giza Based on the Configuration of the Three Stars of the Belt of Orion’, was published in the journal,

Discussions in Egyptology

, Vol. 13, 1989.

A wider thematic vision?Discussions in Egyptology

, Vol. 13, 1989.

No plans or documents have survived in the archaeological record that can shed light on the rationale behind the revolutionary design of the true plane-sided pyramid - the central component of the royal funerary complex, or that can provide textual evidence for a possible thematic vision for the Giza group, or links with other pyramid fields along the western escarpment. This lack of textual evidence limits our ability to interpret the archaeological remains of this exciting period of innovative architectural developments. However, various clues found in the layout of the three complexes, in the ancient Egyptian sky and in the earliest surviving royal funerary texts inscribed within pyramids from the end of the Fifth Dynasty, might suggest a wider thematic vision for the Giza group. These texts provide the ideological background for the idea of an overall thematic vision inspired by the large striking constellation of Orion, or more specifically, the distinctive three-star asterism in Orion commonly known as Orion’s Belt.

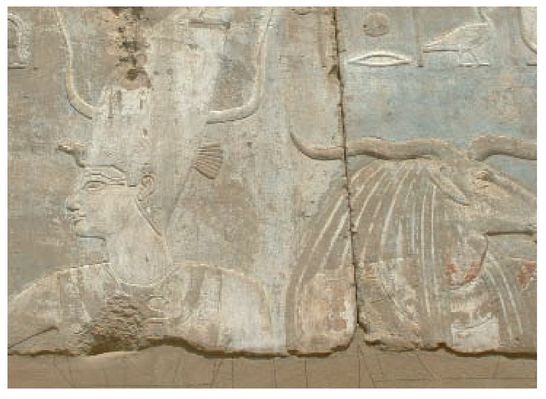

The Temple of Satis (Satet) on Elephantine Island.

Other books

Time Enough for Love by Robert A Heinlein

Swan River by David Reynolds

Children of Prophecy by Stewart, Glynn

Trust (Blind Vows #1) by J. M. Witt

The Innocent by Ian McEwan

Sweet Hoyden by Rachelle Edwards

Autumn Maze by Jon Cleary

A Baby to Care for (Mills & Boon Medical) by Lucy Clark

Gifted and Talented by Wendy Holden

Arrhythmia by Johanna Danninger