The Ellington Century (11 page)

Read The Ellington Century Online

Authors: David Schiff

Chorus III: “Webster solo part II” XA'BA”

X: Webster and rhythm section. Eight bars outside the harmonic progression, using instead a single diminished seventh chord

A': Webster continues

B: Webster continues; six-note brass chords played on downbeats of every other bar

A”: Webster continues

Chorus IV: “Brass” AA'BX

A: A riff-style chordal melody for the brass section

A': Brass continues

B: Baritone sax solo

X: Piano solo

Chorus V: “Sax section” AA'BA”

A: Harmonized melody played by five saxes

A': Sax section continues

B: Sax section continues; melody here seems to allude to the Gershwin tune

A”: Sax section continues

Chorus VI: “Shout” AA'BA

A: Call-and-response between brass and sax choirs

A': Call-and-response extended (brass repeats, saxes vary)

B: Climactic phrase with reeds and brass together

A: Head

In the outline above, the letters attached to phrases refer to harmonic structure, not melody. Note that Ellington's head does not return after each bridge but only at the end of the entire piece. Melodic development takes the place of repetition, just as it does in Beethoven or Brahms. Or the blues.

At once circular (reiterating its phrase structure in the manner of the blues) and linear, “Cotton Tail” builds phrase by phrase, chorus by chorus, to the climactic “tutti” proclamation of VI B. Its form is subtly, systematically asymmetrical: the six choruses are grouped 1 + 2 + 3 (an expanding Fibonacci series that would have pleased Bartók). Three structural anomalies (X) elide the six choruses into a seamless, seismic whole. The last phrase of chorus one, four bars shorter than the expected eight, serves as a jump cut to Webster's entrance. The cropped phrasing tilts the entire structure; everything thereafter seems to arrive ahead of schedule.

Harmonically static, Webster's first solo phrase in chorus two seems to extend the previous stanza as well as beginning a new one. Its structural ambiguity turns Webster's double chorus solo into an asymmetrically subdivided single phrase, 40 + 24 (AABAXABA). The last phrase of chorus four similarly jettisons rhythm changes in favor of a blues oscillation on the piano that sets up the supersax supermelody of chorus five. Although Ellington's static, out-of-time solo comes two thirds of the way through the piece, it feels like its center, the eye of the storm. Form is also a manifestation of rhythm; these strategic formal asymmetries are slo-mo versions of faster off-kilter patterns.

Listening to “Cotton Tail” we can detect five different kinds of rhythm:

1. Pulse rhythm: bass, drums, piano

2. Melodic rhythm: beginning with the head

3. Soloistic (supermelodic) rhythm: first heard in Cootie Williams's plunger solo I B

4. Riff or shout rhythm: first heard emerging in the trombones in I A and Aâ²

5. Harmonic rhythm: the regularly paced temporal exposition of rhythm changes

Each of these rhythms has its own physiognomy, speed, and ancestry. The steady stream of harmonic rhythm, the chord change that happens every two beats like clockwork, is European in origin. The unpredictably exploding shout rhythm, derived from the “ring shout,” has African roots. The steady pulse (234 beats per minute) heard nonstop in the bass and drums relates to two continents, the walking bass of European baroque basso continuo and the “metronome sense” of African drummers. Theorists of rhythm in both European and African music

tell us that rhythm is layered, simultaneously horizontal and vertical. The rhythmic engine driving “Cotton Tail” onward and ever upward counterpoints rhythms and cultures.

Tracking each rhythmic strand in isolation through the piece shows that each one tells its own story.

Pulse Rhythm

Bass (Jimmy Blanton) and drums (Sonny Greer), both improvising, lay down a carpet of steady beats, four to a bar. Unlike the walking bass lines in baroque music (the Prelude in B Minor from

The Well-Tempered Clavier

, Book I, for instance), the inflection of the four beats changes often and unpredictably in both instruments; it's a springy carpet. Between one extreme of four evenly accented beats and the other of two heavy backbeats (one

and

two

and

), Greer also punches the fourth beat at times and ushers in the last phrase of chorus two with a four-note break that says “I Got Rhythm.” Similarly, Blanton varies the inflection by playing either two pairs of notes or four different notes in each bar. The double articulation of pulse by pitched and unpitched instruments, as rhythm and melody, makes the drums speak, the capability for which they were banned during the time of slavery.

Melodic Rhythm

From its first note the head melody bounces off the pulse far more often than it coincides with it; it falls on the downbeat in only three of its eight bars, all even-numbered, structurally weak. This pattern subtly alludes to the melody of “I Got Rhythm,” which similarly avoids the downbeats of strong bars and stresses them in the weak ones. Where the Gershwin song states the same rhythmic pattern three times, normalizing its African cross-rhythms and ending with the reassuring squareness of “Who could ask for anything more?” “Cotton Tail” slyly moves the “anything more” to its fourth bar and then skitters to its close with four over-the-bar-line syncopations.

The head is what musicologists term a “contrafact”âa new melody constructed on an older harmonic progression. The term emits an unfortunate odor of fraudulence that hides the sophisticated musical and cultural transactions at play. As a form of blues, jazz always sets new melodies atop a preexisting harmonic pattern. Contrafacts apply this strategy to popular tunes, but a distinction may be drawn between a

contrafact that is a new popular tune, such as “Meet the Flintstones,” and jazz heads like “Moten Swing” (based on “You, You're Driving Me Crazy”) or Thelonious Monk's “In Walked Bud” (based on “Blue Skies”) or “Lester Leaps In,” Parker's “Anthropology” and “Moose the Mooche,” Sonny Rollins's “Oleo,” Monk's “Rhythm-a-ning,” and “Cotton Tail”âall based on “I Got Rhythm.” These heads do not replace one pop tune with another. Instead, they erect a jazz melody on the ruins, so to speak, of a pop tune, a more complicated and devious kind of melody in conspicuously contentious relation to its pop prototype. This kind of jazz melody reappropriates musical elements back from popular song, exposing a history that the song had relegated to amnesia. Which is the real contrafact?

The bounding melodic pattern of the head, repeatedly sidestepping the downbeat, is an eight-bar rhythmic palimpsest, a jazz rhythm built on a pop rhythm (I-got-rhy-thm) derived from a ragtime hook (Hold-that-tiger) that conjures up West African origins. You can hear Ellington as musical archaeologist at the opening of the “String Session” version of “Cotton Tail”; by emphasizing the oddly placed repetitions of the opening pitch within the melody, he makes it sound like an Afro-Cuban clave or West African handbell. One step higher in the scale than it should be and famously hopping off the downbeat, that first melody note sounds a radically African accent against the American pop tune scaffolding adumbrated by the bass in the absence of chords. That accent erupts more emphatically in the fifth bar when a flatted fifth, ricocheting off the beat, defines the melodic curve.

Supermelody

Jazz melody bounces off the beat; soloistic supermelody freewheels on the offbeats. Webster's two-chorus solo exemplifies supermelody here, darting and hovering beyond the already loosened rhythms of the head. Ellington frames Webster's improvised supermelodies with composed ones: Cootie Williams's plunger solo in I B,

11

Harry Carney's solo in IV B, and then two “supersax” choruses that in effect turn the entire sax section into a single instrument.

Shout

Shout rhythm appears in bursting two- or three-note riffs throughout the piece, gradually emerging from a subservient supporting role

(trombones, sneaking in at the end of I A and building in the following phrase) to lead the call-and-response (in I B, II B, and III B) to the epiphanic glory in VI B. In chorus four the trumpet section, taking up an idea they first announced in I X, builds a riff melody that climaxes in a shower of two-note shouts. Unlike the other rhythmic styles, shout rhythm is always played by instrumental choirsâas a community.

Swing arisesâsomehowâfrom the interaction between these different rhythmic elements. One way to get at how this works is by listening closely to each rhythmic strand, starting with the way Sonny Greer shapes the rhythm by “feathering” the bass drum and playing accents on the drum rim. Students learning to play jazz spend a lot of time going to school with recordings like this one, transcribing and playing solos. But we can also think of swing less as a technical phenomenon than as a cultural, or cross-cultural, one. Swing is as much a matter of cultural perception as of instrumental physics. Let's look at the sources of that perception.

CONTINUO VERSUS CLAVE

The rhythmic language of “Cotton Tail” fuses European and African elements for which I'll use the shorthand terms

continuo

and

clave.

“Continuo” denotes the rhythm of harmonic change. In its harmonic function the rhythm section of a jazz band (guitar, piano, bass, drums) resembles the continuo section of European baroque music (keyboard and bass). As Ned Sublette argues, the appearance of the continuo in European music after 1600 coincided with the popularity of dances like the sarabande and chaconne, which had traveled (with the slave trade) from Africa to the Caribbean and then to Spain.

12

Europeans reinforced the African rhythms with repeated patterns of harmonic motion (basso ostinato, or ground bass) articulated by the bass and keyboard. In baroque music and later European styles the slow and predictable motion of harmonic progressions served as the foundation for more rapid and varied melodic motion; in Bach's Goldberg Variations, a

summa

of ground bass composition, a thirty-two-bar harmonic progression underlies thirty-one pieces that are otherwise completely different in melodic rhythm, tempo, and meter. The rhythm of harmonic changeâcontinuoâshapes twentieth-century American popular songs, and the jazz compositions and improvisations based on them.

West African-derived elements in the rhythmic language of “Cotton Tail” appear in the offbeat rhythms of melody, supermelody, and

shout. Though they may appear complicated, unpredictable, and asymmetric in transcription, these rhythms don't

sound

irregular or disruptive, qualities associated with syncopation in European music (think of those roof-rattling offbeat chords in the first movement of the

Eroica

). Essential rather than secondary, expected rather than exceptional, these asymmetries derive from patterns played by the metal handbell in West African music and the wooden

clave

in Cuban music. West African music is organized around a repeated figure played on a high-pitched metal handbell (

gankogui

in Ewe); in Caribbean music like the Cuban

son

the wooden clave sticks take over this function, while in the United States, where dancing and drumming by slaves was largely banned, hand clapping preserved the African rhythms in patterns such as the familiar “Bo Diddley” rhythm of rock music. For convenience I'll term all the different forms of this rhythm “clave.”

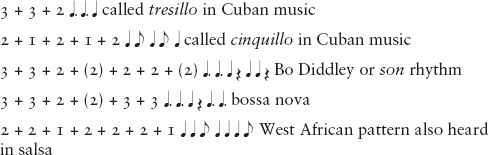

Unlike the beat patterns of European music, clave beats have different lengths. Also unlike European rhythms, which are predominantly based on units of two or four beats, clave patterns are usually in three, five, or seven beats; these asymmetric figures are always felt or played contrapuntally against regular duple foot or drum patterns. Five familiar clave patterns are:

All these patterns add up to either eight, twelve, or sixteen eighth notes, which usually equals either two or four steps.

13

When studying West African music the first thing you learn is the handbell pattern; you then learn, very slowly, how to coordinate that pattern with different figures played on each drum or rattle and also with song and dance. Most of the drums, each of which plays its own rhythmic pattern, are pitched and are played in such a way that their rhythmic patterns also form pitch melodies. The master drummer, overseeing the entire ensemble, indicates changes in sections of a dance and also (uniquely) plays a variety of figures. As you progress, you may come to realize that the terms most often used to describe

the rhythmsâsyncopation, cross-rhythm, and polyrhythmâare mis-leading.

14

There are indeed many different rhythmic figures performed simultaneously, but they are precisely linked components of an overall rhythmic pattern. Or an overall

melodic

pattern, but therein lies a tale. Allow me to share an experiential anecdote of the moment when I got (African) rhythm.

Back in the disco decade, when I was a graduate student at Columbia, I played Ewe music (from southeastern Ghana) for a few years under the guidance of master drummer Alfred Ladzekpo and Professor Nicholas England. We began our study with some simple children's songs, first learning to clap the handbell pattern. Over a period of months I learned to play (in rising order of difficulty)

axatse

(rattle),

kagan

(highest-pitched drum), and

kidi

(medium-pitched drum). The drums were more difficult because, in addition to pounding out a rhythm, I had to manipulate the pitch by using one stick to change the tension of the drumhead. Meanwhile, I would listen carefully for the

gankogui

pattern, which I thought of as corresponding to a European measure; indeed, it is often transcribed that way, misleadingly, because Ewe musicians do not learn their music from notation. To detect the pattern I tried to hear a downbeat; if I could find “one,” then everything else would fall into place, just as it did when I played tuba in my high school marching band. I should have realized that I was in trouble when my perception of

measure; indeed, it is often transcribed that way, misleadingly, because Ewe musicians do not learn their music from notation. To detect the pattern I tried to hear a downbeat; if I could find “one,” then everything else would fall into place, just as it did when I played tuba in my high school marching band. I should have realized that I was in trouble when my perception of , a four-beat pattern, would suddenly shift into

, a four-beat pattern, would suddenly shift into , the same number of eighth-note beats divided into three slower half-note beats.

, the same number of eighth-note beats divided into three slower half-note beats.