The Emperor's Knives (50 page)

Read The Emperor's Knives Online

Authors: Anthony Riches

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Action & Adventure, #War & Military

As the popularity of the games spread, schools were established to train gladiators for the spectacles, which proved handy when the empire was under pressure and needed military training in a hurry (but troubling when an escaped gladiator called Spartacus ran amok at the head of an army of freed slaves for two years). As the republic became increasingly unstable, it became normal for the aristocracy, especially those with political ambitions, to be escorted around the city by teams of gladiators who were paid to protect them from the potential intimidation of their rivals. In short, with purpose-built arenas – amphitheatres, from the Latin word ‘

amphi

’ (oval) – starting to spring up, and with Caesar hosting the first state-sponsored games in 42

BC

, the gladiatorial

munus

had become an established feature of Roman society.

For men who exercised such a strong influence on Rome’s society, the life of the average gladiator wasn’t all that enjoyable for the great majority of men lacking in the skills and single-minded brutality to fight their way through to the

rudis

, the wooden sword that released a man from his contract. The gladiator, for all that many respectable married women seem to have been drawn to their presence – and brutal ‘bad boy’ sexuality – like moths to a flame, were nevertheless (and quite possibly in partial consequence), considered to be the lowest strata of Roman society, openly despised by even the empire’s slaves even while the latter were all but worshipping the best-known fighters. Not that every man who fought in the arena will have had very much choice in the matter. Criminals, if they were lucky enough not to find themselves condemned to participate in the gory lunchtime shows by being ripped to pieces by hungry animals –

damnatio ad bestias

– could simply be condemned to the games –

damnatio ad ludos

– a form of punishment from which a determined, skilful and above all lucky man might still win his freedom. Worse than this was to be condemned to the sword –

damnatio ad gladium

– a genuine death sentence, whether in the condemned man’s first fight or his thirty-first. Inevitably, however, reasonable numbers of both suitably skilled and quite unsuited men volunteered to fight in the arena in return for financial reward. Whether to pay off a particularly unpleasant debtor – who would quite likely be using gladiators as the means of collecting what he was owed – to impress a girl, or simply to make his fortune, men voluntarily sold their bodies into the ludi, the gladiatorial schools. In doing so, and quite apart from lowering their status to that of infamis, the scum of society, unable to vote, hold public office or even buy a burial plot, and shunned by all and sundry for fear their status might be communicable, they submitted to an oath which put their lives utterly at the mercy of a

lanista

, the man who owned them until they were killed, invalided or freed. The great majority of them would eventually leave the arena with either a life-threatening or fatal wound, in which latter case their skulls would have been stoved in by a man with a large hammer, dressed in the costume of an ancient Etruscan god and whose job it was to ensure that a man who looked dead really had nothing more calculated on his mind.

One last class of men fought in the arena, the

auctorati

: men who came to exercise their need for danger. These days thrill seekers jump out of aircraft or climb mountains to get their kicks, but in ancient Rome the lure of the games seems to have exerted a powerful pull on those men (and perhaps the occasional woman) determined to demonstrate their

virtus causa,

their skill at arms. This was barely acceptable, as long as the man was careful to preserve some degree of anonymity behind a faceless helmet and spare his family and friends the shame of his degradation, although the emperor Commodus shattered that social convention by appearing in what were presumably carefully rigged contests late in his ill-starred reign.

Over a dozen different types of gladiator fought and died in the empire’s arenas over several centuries, one class of fighters who were effectively heavy infantrymen taking on another group of nimble small shield fighters, who depended on their speed and skill to defeat slower and better protected opponents. The classic combination was that of the

retarius

– the net man – who sought to snare his opponent the

secutor

– the chaser – with a net, keeping him at arm’s length with a trident, while the

secutor

pursued him with every intention of battering and hacking him to death.

Speciality acts also abounded, like the

andabatae

– two fighters blinded by helmets covering their faces – and the dimachaerus, fighting without a shield but using two swords to mount a constant assault on his would-be victim. Chariot fighters were popular while Rome’s conquests over the barbarian tribes of the north – Gauls, Germans and Britons – provided a ready supply of suitably trained captives. Indeed the arenas thrived on prisoners, Rome’s wars providing a constant flow of raw material from around the empire’s periphery, men unsuitable to be sold into domestic slavery due to their aggressive natures or simple lack of any saleable skill being used instead to provide the population with bloody entertainment. After his huge victory in the war with Dacia, the emperor Trajan hosted 123 days of games in which over 5,000 pairs of gladiators, many of them captured Dacian warriors, fought to the death. It was no coincidence that two of the four gladiatorial schools were named after the styles of fighting that these men brought with them, the

Ludus Gallicus

(Gaulish School) which produced heavy fighters like the

secutor

and the

murmillo

(fish man, after his crested helmet, usually armed much like a legionary) and the

Ludus Dacius

(Dacian School) which turned out the more nimble

retarius

and

thracian

(a highly mobile fighter whose best hope was to stab his lumbering enemy in the back with his curved blade).

And, by the same token, it was no coincidence that as the empire slid into the chaos of the third century, the games became less grand, due both to financial crises and a lack of the previously abundant prisoners of war. But for all of the reduction in expenditure on the games, and the empire’s vaunted conversion to the more apparently ethical Christian religion, the popularity of the gladiatorial ludi was largely unchanged. Despite the higher moral standards espoused by the state, the games proved remarkably stubborn in their continuing popularity, although theatrical shows and chariot races gradually rose to prominence, not least, one suspects, because they were quite simply cheaper to stage and therefore held more frequently. The end seems to have come with the death of an Egyptian monk by the name of Telemachus, martyred while protesting at the games held to celebrate defeat over the Goths during the reign of the emperor Honorius, his death proving the catalyst for the emperor to outlaw the games – although it still took more than one imperial decree to put a conclusive end to the munera. The last fight was held on the first day of January in the year

AD

404.

I hope

The Emperor’s Knives

will provide the reader with some feeling for the glory and terror that accompanied the many thousands of gladiators who endured their new status of infamis in order to fight for money, for their freedom or simply to see another sunrise.

THE ROMAN ARMY IN 182

AD

By the late second century, the point at which the

Empire

series begins, the Imperial Roman Army had long since evolved into a stable organisation with a stable

modus operandi.

Thirty or so

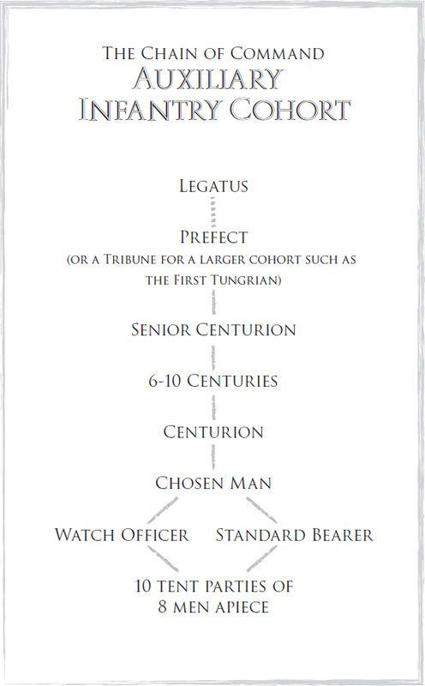

legions

(there’s still some debate about the Ninth Legion’s fate), each with an official strength of 5,500 legionaries, formed the army’s 165,000-man heavy infantry backbone, while 360 or so

auxiliary cohorts

(each of them the equivalent of a 600-man infantry battalion) provided another 217,000 soldiers for the empire’s defence.

Positioned mainly in the empire’s border provinces, these forces performed two main tasks. Whilst ostensibly providing a strong means of defence against external attack, their role was just as much about maintaining Roman rule in the most challenging of the empire’s subject territories. It was no coincidence that the troublesome provinces of Britain and Dacia were deemed to require 60 and 44 auxiliary cohorts respectively, almost a quarter of the total available. It should be noted, however, that whilst their overall strategic task was the same, the terms under the two halves of the army served were quite different.

The legions, the primary Roman military unit for conducting warfare at the operational or theatre level, had been in existence since early in the republic, hundreds of years before. They were composed mainly of close-order heavy infantry, well-drilled and highly motivated, recruited on a professional basis and, critically to an understanding of their place in Roman society, manned by soldiers who were Roman citizens. The jobless poor were thus provided with a route to both citizenship and a valuable trade, since service with the legions was as much about construction – fortresses, roads and even major defensive works such as Hadrian’s Wall – as destruction. Vitally for the maintenance of the empire’s borders, this attractiveness of service made a large standing field army a possibility, and allowed for both the control and defence of the conquered territories.

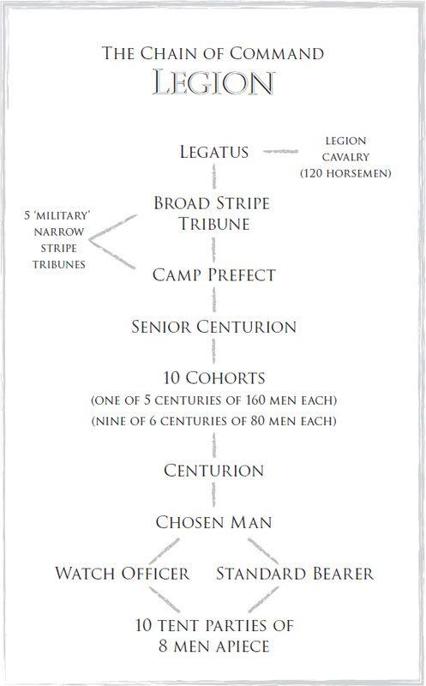

By this point in Britannia’s history three legions were positioned to control the restive peoples both beyond and behind the province’s borders. These were the 2nd, based in South Wales, the 20th, watching North Wales, and the 6th, positioned to the east of the Pennine range and ready to respond to any trouble on the northern frontier. Each of these legions was commanded by a

legatus

, an experienced man of senatorial rank deemed worthy of the responsibility and appointed by the emperor. The command structure beneath the legatus was a delicate balance, combining the requirement for training and advancing Rome’s young aristocrats for their future roles with the necessity for the legion to be led into battle by experienced and hardened officers.

Directly beneath the legatus were a half-dozen or so

military tribunes

, one of them a young man of the senatorial class called the

broad stripe tribune

after the broad senatorial stripe on his tunic. This relatively inexperienced man – it would have been his first official position – acted as the legion’s second-in-command, despite being a relatively tender age when compared with the men around him. The remainder of the military tribunes were

narrow stripes

, men of the equestrian class who usually already had some command experience under their belts from leading an auxiliary cohort. Intriguingly, since the more experienced narrow-stripe tribunes effectively reported to the broad stripe, such a reversal of the usual military conventions around fitness for command must have made for some interesting man-management situations. The legion’s third in command was the camp

prefect

, an older and more experienced soldier, usually a former centurion deemed worthy of one last role in the legion’s service before retirement, usually for one year. He would by necessity have been a steady hand, operating as the voice of experience in advising the legion’s senior officers as to the realities of warfare and the management of the legion’s soldiers.

Reporting into this command structure were ten

cohorts

of soldiers, each one composed of a number of eighty-man

centuries

. Each century was a collection of ten

tent parties

– eight men who literally shared a tent when out in the field. Nine of the cohorts had six centuries, and an establishment strength of 480 men, whilst the prestigious

first cohort

, commanded by the legion’s

senior centurion

, was composed of five double-strength centuries and therefore fielded 800 soldiers when fully manned. This organisation provided the legion with its cutting edge: 5,000 or so well-trained heavy infantrymen operating in regiment and company-sized units, and led by battle-hardened officers, the legion’s centurions, men whose position was usually achieved by dint of their demonstrated leadership skills.